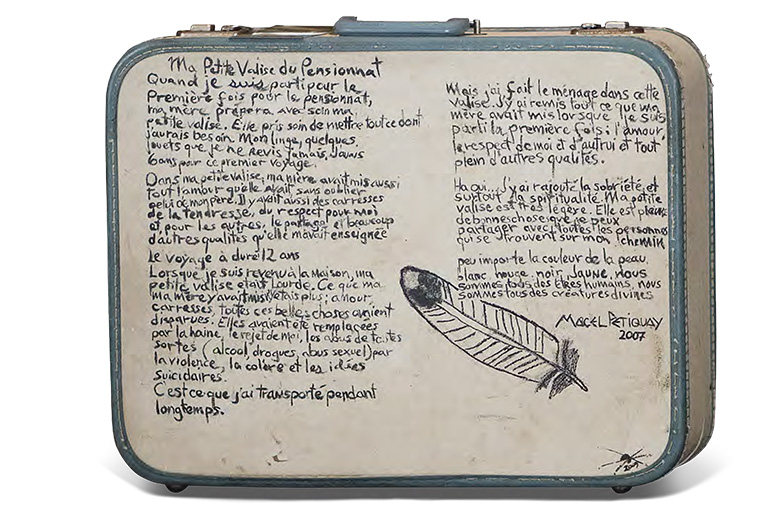

Residential School Student's Suitcase

This poem-object offers a powerful testimony on behalf of the 150,000 children forcibly taken from their families, separated from their communities, and placed in Indigenous residential schools. These waves of removal continued into the 1980s.

Between 1870 and 1997, Christian churches and the Canadian government jointly managed 139 establishments of this type that were spread across the country. Children in the schools were made to adopt Christianity, stop speaking their mother tongue, and switch to French or English.

Living conditions were appalling for these children, who could experience malnutrition, an absence of care, or even sexual abuse. Furthermore, the removal of children from their families left indelible scars on entire communities that, from one day to the next, were deprived of their children’s voices and laughter. In 2015, with the publication of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s report, the federal government officially apologized and asked forgiveness for this cultural genocide.

This work, titled Ma petite valise de pensionnat (My Little Residential School Suitcase), illustrates the violent trauma these children sustained. The creator, Marcel Pititkwe, an Atikamekw from Wemotaci, Quebec, was only six years old when he was placed in the residential school in Amos, Quebec. In the suitcase, his mother had lovingly wrapped his clothes, along with his favourite toys that his father had made. Upon arriving at the school, the case was immediately taken from him, and Marcel Pititkwe became “Marcel Petiquay.”

Pititkwe survived twelve years of abuse. Both the poem and the suitcase bear witness to his personal journey: from a loving childhood to feelings of shame, struggles with dependency, suicidal thoughts, and, finally, healing. Today, Marcel Pititkwe, once again proud of his culture, actively works towards reconciliation. The eagle feather (a symbol of peace) that adorns the end of his poem is a wonderful expression of these efforts.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.