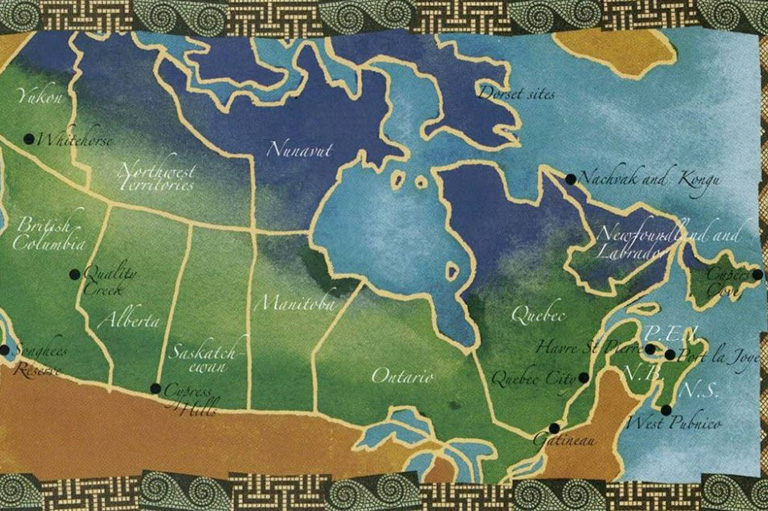

Havre Saint Pierre and Port-la-Joye, P.E.I: A tale of two families

Prince Edward Island, home to the Mi’kmaq, lay virtually untouched by European settlement until the beginning of the 18th century. After the cession of Acadia to England by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, a number of Acadians moved to nearby French possessions.

Among them were two families seeking a new home on the island then known as Île Saint-Jean. They had similar beginnings, but very different fates.

In 1720, Michel Haché dit Gallant, the orphaned son of an Indigenous mother and French father, arrived in Port-la-Joye, one of the island’s earliest French settlements, with his wife, Anne, and four of their 12 children.

A prosperous man, Gallant is believed to have been harbourmaster. He and his extended family eventually occupied nine of the 15 properties in the community near present-day Charlottetown.

In his 70s Gallant slipped through the ice of the North River and perished in 1737, never living to see the war with Britain in 1744, which led to the torching of his house in 1745, or the Acadian expulsion of 1758.

While Gallant was settling in Port-la-Joye, an Acadian farmer named Jacques Oudy brought his family to settle in Havre Saint-Pierre, the second French settlement, on the northeast coast of the island, near present-day Morelle on St. Peter’s Bay. Oudy and his wife raised 14 children who eventually comprised the majority of the community.

Spared the British destruction of 1745, the farming Oudy clan grew crops of wheat, oats, peas and linseed to supply the occupying forces at the fortress at Louisbourg on Île Royale (Cape Breton Island).

Rob Ferguson, an archaeologist with Parks Canada, set out 141 years later, in 1999, to find the original site of Havre Saint-Pierre.

Though the area was known to be the location of an early French settlement previous to British occupation, 200 years of the farmer’s plough had removed all traces, and neither surface features nor air photographs revealed any clues to the location.

With the help of remote sensing, local folklore and a 1764 British survey map discovered in Charlottetown by archaeologist Scott Buchanan, Ferguson and his colleagues located three of the nine original Oudy homes, including a rich French midden (refuse pile) discovered beneath the remains of a British cellar, believed to be from the home of the original patriarch Jacques Oudy and his family.

Excavations have unearthed from the three French homesites the remains of a blacksmith forge, rarely seen Chinese porcelain, shards of brightly glazed green ceramic bowls from the Saintonge area of France and a number of seed samples.

Scientific examination of the seed samples has revealed some startling information -the presence of a fungus known as sclerota of ergot, commonly found in rye, known to cause convulsions, hallucinations and gangrene.

The Gallant ancestral properties, on the southwest side of Charlottetown Harbour, today form part of the Port-la-Joye-Fort Amherst National Historic Site.

Ferguson’s archaeological excavations here, examining the period from 1720 to 1758, have revealed fine kitchenware and fancy ceramics from Germany, Britain and Italy, evidence that the affluent Gallant provided well for his family.

Fortunately, Gallant’s family survived the deportation, and Gallant would have been proud to know that his descendants were on hand to mark the 250th anniversary of the Acadian expulsion in 2005.

Unlike the Gallants, the farming Oudy clan seems to have vanished from the historical record. During the expulsion of Acadians from Île Saint-Jean in 1758, it is believed the entire Oudy clan boarded the ill-fated La Violet for the voyage to France, perishing when the ship went down in the Atlantic.

Despite exhaustive searches of Canadian, French and genealogical records by Ferguson and his colleagues, all that remains of the extended Oudy family are archaeological traces in the rich soils of Prince Edward Island.

Visit Port-la-Joye-Fort Amherst National Historic Site online. The entire 1752 census of Île Saint-Jean, including all members of the Oudy family, can be found at IslandRegister.com/1752.html.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement