Mercy Mission

Constance “Connie” Beattie was the only real choice to answer a distress call issued by the Department of Indian Affairs in late March 1949.

A physiotherapist was urgently needed to help treat Inuit polio victims in the Arctic settlement of Chesterfield Inlet on the west coast of Hudson Bay.

It would be an unprecedented mission in response to an unprecedented and especially tragic polio epidemic that struck during the winter of 1948–49, seemingly seeking out a large proportion of the immunologically vulnerable Inuit population. There were about 275 Inuit, along with 25 non-Inuit, living in and around the outpost.

Connie was twenty-four-years-old. She grew up in Brockville, Ontario, and graduated from the University of Toronto’s physiotherapy program in 1945 before serving in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps.

In 1948 she joined Toronto East General Hospital’s physiotherapy department and very quickly became its head. She was also president of the Toronto branch of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association, which was where officials from the Department of Indian Affairs started their search.

Connie wasted little time in volunteering her services. “It will be a thrilling adventure and a chance to help those... who don’t have half the chance that polio victims get down here,” she told the press on April 2, 1949.

A month earlier, North American newspapers first reported the alarming news of a mysterious epidemic striking Chesterfield Inlet — Igluligaarjuk in Inuktitut — the oldest permanent settlement in Nunavut and the hub of the Keewatin District.

Early reports said eleven Inuit had died from the disease, which appeared similar to poliomyelitis, but noted that “white persons” seemed to have escaped it.

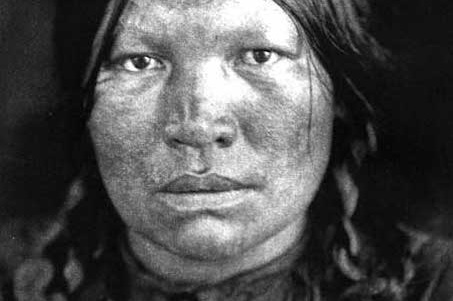

Very little about the outbreak fit what was known about polio at the time, especially the way “the crippler” had struck so far north in the middle of winter when the average temperature was near minus forty degrees Celsius. One sixth of the Inuit population in the immediate area was affected, including many adults, leaving them with varying degrees of paralysis.

Dr. Joseph P. Moody, the federal government’s medical officer of health for the Eastern Arctic and resident physician at Chesterfield, took the unprecedented step of ordering the quarantine of more than one hundred thousand square kilometres surrounding the outpost, tightly restricting the movement of the vast area’s six hundred or so mostly nomadic Inuit. The massive quarantine would remain in place for almost nine months.

Leaflets written in syllabic Inuktitut, the main Inuit language, warned of a disease that could cripple and kill people of all ages. They also noted that those who were well or sick could spread the disease and emphasized the importance of avoiding the affected area and anyone in it until further notice.

On March 2, 1949, a team of five doctors arrived at Chesterfield from Winnipeg. After a few days of investigating the outbreak, treating cases in St. Theresa Hospital and gathering specimens for laboratory tests, the doctors returned to Winnipeg on an RCAF Dakota. Also on board were thirteen Inuit polio patients for further treatment at Winnipeg’s King George Hospital. Twelve were partially paralyzed “stretcher cases,” as the Globe and Mail described them, the oldest a forty-five-year-old man; six were under the age of twelve. All would need specialized physiotherapy.

Just as the flight left the outpost, Moody confirmed that polio was indeed the cause of death of at least one of the Inuit: Nagjuk, a much revered elder and shaman healer. An autopsy revealed the unmistakable pathology of poliomyelitis in his spinal cord. Nagjuk had not been co-operative in trying to stop the epidemic, despite several deaths occurring each night due to the virus impairing respiratory muscles. “I am not able to do anything, because I was told not to,” Nagjuk is quoted as saying in a 2002 Nunavut Arctic College document.

He foresaw many deaths due to a broken taboo, and despite desperate pleas, including from his wife, he refused to do anything. He remained well but was convinced that his whole family would die unless he died first. When one of his grandchildren succumbed to the disease, Nagjuk was found dead the next morning. However, no more family members died, and those who were sick recovered.

News of the Arctic polio epidemic spread quickly in Canadian and American newspapers. The reports focused on its severity and rarity, with doctors and scientists struggling to explain the unprecedented crisis.

Many experts doubted that polio was the real cause. A physician from New York City wrote to the Manitoba minister of health and public welfare, seeking information about “the so-called polio victims under treatment in Manitoba.” In the loaded language of the time, he wrote that it seemed “hardly believable that a summer disease like poliomyelitis, which usually affects people with high modern sanitary standards, should cause a winter epidemic amongst natives of the frozen north with their primitive living conditions.”

Leading polio researchers pressed Dr. Andrew J. Rhodes of Connaught Medical Research Laboratories at the University of Toronto to expedite the testing of specimens from Chesterfield Inlet. Rhodes, a foremost virus specialist with special expertise in polio, had been recruited from the United Kingdom in 1947 to lead a comprehensive poliovirus research program.

By the end of April 1949, Rhodes was able to confirm the presence of the poliovirus in specimens from five Inuit cases. There was now no doubt about the polio diagnosis, but researchers were uncertain how to explain its presence in such unusual geographic and climate conditions. And why was it striking this traditional nomadic population with such severity? Rhodes was not aware that polio had struck the Arctic region before. There had been several outbreaks among the Greenland Inuit, most notably one in 1925 that caused twenty-seven deaths among a population of eight hundred.

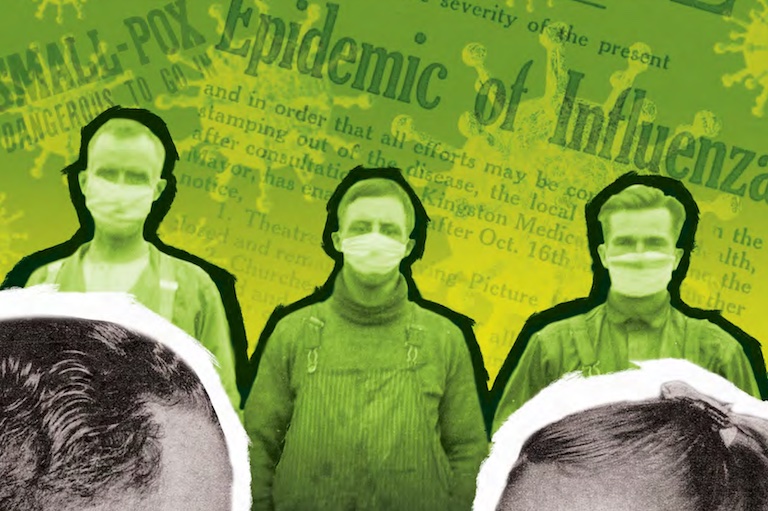

POLIOMYELITIS: A MYSTERIOUS ENEMY VANQUISHED

Not long ago, polio — short for poliomyelitis — was one of the most feared diseases on the planet. Highly infectious, it does not usually have visible symptoms, and about three quarters of sufferers recover in a few days. In the other one quarter of victims, though, the poliovirus can turn deadly, attacking the spinal cord.

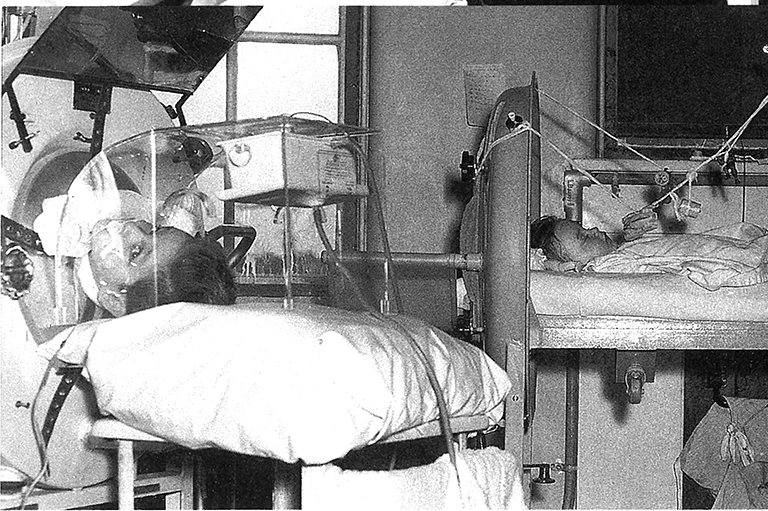

Victims can develop meningitis and paralysis, which in turn lead to death in as many as ten per cent of those stricken, when their breathing and swallowing muscles are weakened or paralyzed. The only treatment was the iron lung, developed in the late 1920s, which forced air in and out of the lungs. Before the advent of vaccines in the mid-1950s, polio was a terrifyingly common and indiscriminate scourge.

Polio epidemics first emerged during the late nineteenth century and worsened through the first half of the twentieth, ironically because of improving public health standards limiting what had been all but universal circulation of the poliovirus among infants. By the late 1940s, polio was the middle-class plague, mostly striking otherwise healthy children as well as increasing numbers of adults, particularly in new postwar suburbs.

Polio epidemics peaked in Canada in 1953 with some nine thousand cases and five hundred deaths. Much remained mysterious and uniquely frightening about polio during the late 1940s. With epidemics typically starting during the summer “polio season,” the popular and scientific view of “the crippler” as a warm-weather threat was reinforced in North America.

Widespread immunization programs started in 1955 with the vaccine developed by Dr. Jonas Salk and changed everything. The last polio case in Canada was in the 1970s, and the country was certified polio-free in 1994. Worldwide incidence has declined ninety-nine per cent since 1988. Polio remains active only in Pakistan and Afghanistan, according to the World Health Organization.

Based on Moody’s initial investigations, the outbreak was traced to September 1948 and a person named Tutu, who was described in a Toronto Star report as “a tough young hunter.” After a good season of caribou hunting, Tutu went to Churchill, Manitoba, to trade some ivory carvings. There he likely came into contact with someone who was infected with polio but not showing symptoms, and became a carrier himself. He then took a month-long journey home, visiting many camps and settlements, all the while unwittingly spreading polio — an Arctic “Typhoid Mary,” as a Toronto Star report suggested.

More detailed epidemiological investigations traced the origin of the outbreak further back to July 1948.

During the first week of October, two cases of paralytic polio developed in the Inuit camp of Nunella and three in Eskimo Point, now known as Arviat, Nunavut. One of the Nunella cases was an Anglican missionary, the other an Inuk RCMP special constable, Jimmy Gibbons, who developed paralysis in his arms. Gibbons soon travelled to Padlei, where seven paralytic cases, two resulting in death, developed by late December.

More detailed epidemiological investigations traced the origin of the outbreak further back, to July 1948. An Inuk man contracted polio north of Churchill in early July; in late September, he was flown to Winnipeg for physiotherapy treatment of his left leg. The same month, and in the same region, a young Chipewyan girl was also stricken with polio.

The original source of polio in the Churchill area was a member of the Royal Canadian Air Force, who was flown to Winnipeg and diagnosed with polio soon after he arrived. Moody had not been informed of the case, despite Churchill’s location on the border of his jurisdiction.

Father Henri-Paul Dionne, a Roman Catholic missionary, was the likely connection between the first polio outbreak and the start of the epidemic in Chesterfield Inlet. He flew to Chesterfield from Eskimo Point on January 28, 1949. He did not show symptoms, although it was clear that he had visited polio victims in Eskimo Point. While in Chesterfield, he stayed in the outpost’s hospital, visited patients, and mingled among the white and Inuit populations.

Five days after his departure on February 9, the first of many polio cases emerged in Chesterfield. Within two weeks, fifteen of the twenty-five Inuit who were in the hospital developed polio; three died, and eight were paralyzed.

An unusually mild fall and an early winter season set the stage for polio to spread among the vulnerable Inuit population in the area. Warmer than normal temperatures led to the spoiling of caribou meat caches that would otherwise have remained frozen into the winter. During January and February, many Inuit were forced to travel to Chesterfield Inlet to buy food from the store, becoming exposed to the virus in the process.

By the end of March, some sixty polio cases appeared in a population of about 275. Thirty-eight were paralyzed, and thirteen died from respiratory complications. According to Moody, however, the majority of sufferers were not seriously paralyzed. He felt that several of the cases would benefit from physiotherapy but advised against evacuating them to Winnipeg. Instead, he suggested the assistance of a person trained in orthopaedic exercises — a person like Connie Beattie.

Beattie committed to spending four months in Chesterfield Inlet, working closely with Moody and the Grey Nun nurses at St. Theresa Hospital. As newspaper reports noted, she would not have to live in an igloo but would sleep in the seven-bed mission hospital. The epidemic forced improvisations to add twenty-eight more beds.

Beattie’s Arctic adventure actually began in Winnipeg on April 11, after a hurried flight from Toronto following the annual congress of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association, which she had organized.

She spent three weeks at Winnipeg’s King George Hospital assisting with the care of the thirteen Inuit polio patients from Chesterfield. But, as she noted in a letter published in the June 1949 issue of the Journal of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association, there had essentially been “no physio” provided so far. Despite “the Winnipeg girls doing a noble job,” she said, the hospital desperately needed a physiotherapist, especially for the Inuit patients.

Beattie focused most of her attention on two of the Inuit boys, six-year-old George Tanniak and five-year-old Simeone Yerak, whom she would accompany back to Chesterfield for additional physiotherapy. As an isolation hospital, King George was not suitable for a therapy program involving walking. However, with some specialized equipment flown up to the Chesterfield hospital, Beattie could expedite the recovery of the boys and the other patients.

Much of her time in Winnipeg was spent getting properly outfitted for an Arctic spring and summer with the help of RCAF pilots familiar with the North. Because there were no appropriate women’s clothes at the Fort Osborne Barracks in Winnipeg, she had to look in the men’s department of several Winnipeg stores. She was soon outfitted with a huge parka, over-pants, flannel shirts, and flight boots, writing that the “daintiest article is a pair of knee high rubber boots — laced!”

In short, as Beattie wrote in her letter to the physiotherapy journal just before heading north, “Nobody knows anything about women in the Arctic — what they do, what they wear or anything. The Army gave me the wrong size warm stuff and nothing else, so I’ve been in a complete flap.”

Her frazzled state persisted when, on April 24, she finally boarded the RCAF Dakota heading to Chesterfield Inlet via Churchill. Her luggage was somehow misplaced, and she had to leave without it. Besides the Inuit boys, also on board were four doctors and a nurse from the Department of Indian Affairs.

A department secretary sent a letter to Beattie’s parents, informing them of her safe arrival in Chesterfield on April 26. The secretary also mentioned, “I had not associated this Miss Beattie with the little girl I knew to be your daughter when I lived in Brockville. I hope she will enjoy her work with this service. I know that it will be a great, if unusual experience for her.”

On May 6, the day after the doctors and nurse returned to Winnipeg, Connie sent her mother a telegram for Mother’s Day. She was happy and healthy and gaining weight, and she noted that at twenty-two degrees Fahrenheit (about minus six degrees Celsius), “it’s hot here.”

People in the area quickly became fond of Beattie, as Moody recalled in his 1955 book, Arctic Doctor. To the local Inuit, she was Isuaksiajikulaq, or “young doctor.” She was a competent and cheerful assistant to Moody and did remarkable therapeutic work among the forty polio patients left with residual paralysis, providing therapy to patients in the hospital and in their igloos. She was also a welcome companion to Moody’s wife and young daughter when he went on patrols.

An important part of Beattie’s treatment involved applying hot packs to weak and paralyzed muscles, a technique pioneered by Australian nurse Sister Elizabeth Kenny in the 1930s. In 1940, Kenny moved to the U.S. to promote her method and directly challenged the standard medical treatment of polio in North America, which had long been based on splints and surgery. By the late 1940s, the Kenny method was the prevailing treatment method and promoted a more active physiotherapy-based approach. In a letter home Beattie stressed, “Arctic or no Arctic, I am still hotpacking!” She often had to melt snow to obtain water for the treatments.

Beattie wrote home frequently, occasionally confessing to bouts of loneliness. Her letters were sometimes accompanied by film canisters whose contents bore out her passion for photography. Among the snapshots were many showing her smiling brightly in the snow against a brilliant blue sky. She also kept in touch with her “physio” colleagues, who saw her as a pioneer of the growing specialty.

Beattie spent much of her spare time with Rita and Ken Koehler, who had been posted to Chesterfield Inlet for Ken’s work. She built a close friendship with Rita that provided more of a personal connection with home than was possible with the priests and nuns. In mid-May, she wrote that she expected to be home by the end of August, although, she said, “we can’t depend upon transportation up here.”

After a fairly quiet spring and early summer, Beattie was surprised to learn that she would be leaving two weeks earlier than expected. It was a scramble to be ready on time, and also to say her goodbyes, although she did not tell her parents she was heading home. She’d wait until getting to Winnipeg, “as Mother would worry herself sick.” She was eager to get back; she had plans to marry Dr. Guthrie Grant of Brooklin, Ontario.

The earlier departure was to facilitate the flight plan of the amphibious RCAF Canso aircraft that would transfer several federal transportation department personnel to a remote weather station on Baffin Island before making stops at Chesterfield Inlet and Churchill on August 21 en route back to Winnipeg. Although Beattie had completed her Arctic assignment, and eight polio patients with the most serious symptoms would accompany her on the flight, Moody wrote, “we dreaded having her go back to civilization.”

The plane caused a commotion as it splash-landed on the water of Chesterfield Inlet. Moody’s wife, Viola, prepared a farewell dinner of Arctic trout for Beattie and the plane’s crew. According to Moody, the evacuation of eight paralyzed Inuit people was a “pitiful sight. Many young men, formerly great hunters, were carried out with arms and legs dangling helplessly.”

Moreover, Moody could not help wondering who would take care of their families: “Or, with father dead and son lame, who would hunt the caribou? Who would replace the dead infants with new babies, now that the wife was a helpless cripple?” The remaining Inuit grieved as they watched their friends and family members carried onto the canoe that took them to the plane. Several of the younger patients resisted, until they understood that Beattie would also be going. Everyone finally waved farewell, and, as Moody observed, “Miss Beattie waved back bravely and laughed and called out something about seeing us again."

Connie Beattie’s smiling face dominated the front page of the Toronto Star’s August 22 edition, but it was placed below an alarming headline: “20 Missing On Mercy Plane: Comb Barren North For Mercy Aircraft; Ontario Girl Aboard.” With enough fuel for ten hours, the Canso plane had left Churchill at 6:00 p.m. on August 21 and checked in three hours later with the Hudson Bay station; the last radio contact was at 10:55, shortly after it was to have arrived in Winnipeg.

The report noted that Beattie was looking after seven patients “crippled by polio,” although it was later reported as eight. Also on board was a crew of seven, Canadian Press reporter Jack Aveson, who was returning from a northern assignment, and four federal transportation department inspectors on their way home after long duty spells in northern outposts. Like the story of the Arctic polio epidemic itself, news of the missing “mercy flight” spread quickly in the North American press. In hopes that the plane had landed on one of the numerous lakes of northern Manitoba due to some combination of engine trouble and stormy weather, an intensive search effort was launched. Soon there were additional aircraft and a parachute team. The effort included planes from Trenton, Ontario, and even the U.S. army.

Late on August 22, after receiving several reports of parachute flares lighting up the storm-swept area, and a trapper sighting a column of smoke, the search teams found the crash site. Newspapers on August 23 reported the grim news that the Canso had crashed and all twenty-one on board were very likely killed.

The front page of the August 23 Toronto Star featured Connie Beattie in her University of Toronto graduation photo, along with a picture of her fiancé, Guthrie Grant. As soon as he heard the plane was missing, Grant had set out on a Trenton-based RCAF search plane for Winnipeg; although by the time he arrived he knew that the Canso had been found with no signs of life.

Nevertheless, he remained hopeful of a miracle and stood vigilant at the search team operations centre, listening to the radio messages that confirmed the team’s arrival at the crash scene 438 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg. He was soon able to fly to a lake near the crash site in hopes, he said, that “we might find someone alive, surely ....”

While initial reports suggested that the crash site was little more than burned-out wreckage, a Winnipeg Tribune reporter’s first-hand account described a gruesome scene of the mangled plane and mutilated bodies with minimal signs of fire. His report included photos showing personal effects strewn about the scene, several of which had clearly belonged to Beattie: a pair of high-heeled shoes, women’s magazines, a pocket camera that had sprung open exposing its film, and several photographs she had taken.

In contrast to the personal details given about the white victims of the crash, the extensive newspaper coverage said very little about the plane’s Inuit passengers, other than to note that their bodies were taken for burial in a single grave near Norway House at the head of Lake Winnipeg. After a difficult recovery effort due to the condition of most of the bodies, the remains of the thirteen white passengers were taken to Winnipeg and ultimately sent home. Grant, along with a cousin of Beattie, claimed her body and took it home to Brockville.

An article in the August 25 edition of the Toronto Star seems to have been the only contemporary report to publish the names of the Inuit victims of the crash. The three Inuit girls were identified as Anayasee and Annartosi (both age ten) and Ublureak (fifteen). The men named were Arnalukitar (sixty-five), Akrolayuk (twenty-five), and Ohoto (twenty-seven), and the one woman was identified as Anglalik (twenty-five).

Relatives in the Chesterfield Inlet area were not told of the unmarked mass grave, the exact location of which would not be discovered until a grandson of one of the crash victims tracked it down some sixty years later. At about the same time, Annie Ollie asked a lawyer to help find information on the crash that had killed Ublureak, who was her father’s younger sister. The names of the other Inuit killed in the crash were not again published until a series of articles by Catherine Mitchell appeared in the Winnipeg Free Press in 2009. The double tragedy of polio and the crash affected one family especially hard: Hilarie Arnaluktituaq, her son-in-law John Agajaaluk, and granddaughters Agnes Kappi and Elizabeth Annaqtusi all died.

In December 2007, Ollie and another crash victim’s relative visited the gravesite near Norway House and met several local residents who remembered what had happened. As soon as they had learned of the crash, members of the First Nations community had flown to the crash site to help with the recovery of the Inuit remains. After prayers were recited, the remains were laid so that their faces were looking to the east and the sunrise, a Norway House tradition.

Connie Beattie’s personal story of service in response to the Arctic polio tragedy, coupled with her own shocking death, played out prominently in the Canadian media. Her death hit her fellow physiotherapists especially hard. Indeed, as a report in the September 1949 issue of the Journal of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association noted, “she had served where no physio had served before.” Her legacy has lived on, most notably with the establishment of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association’s Constance Beattie Memorial Fund bursary program. The fund was designed to support post-graduate training in physiotherapy, originally with preference for work in the treatment of polio.

Fundraising dances at the University of Toronto, organized by physiotherapy students, and concerts at Massey Hall helped to launch the fund; the bursary program continues to this day. The Rotary Club in Brockville led the construction of an arts and crafts building at Merrywood of the Rideau, a camp for children with disabilities located near Perth, Ontario. With most of the children using the new building having been affected by polio, a local newspaper report noted, “it is indeed fitting that this addition be a memorial to ‘Connie’ who gave her life to treat polio-infected Inuit.”

The Arctic polio epidemic and its aftermath weighed heavily on the Inuit of the District of Keewatin, who would refuse all medical evacuations for a long time. As Moody put it, this great disaster pursued them “like a nemesis. By direct action, it had crippled a race. Indirectly, it had been responsible for a plane crash that added another blow to the thinning of the ranks of the coastal and Caribou (Inuit).”

However, amidst all the tragedy surrounding this unique epidemic, much of scientific significance was learned about the epidemiology of polio, and especially about its immunology. This knowledge would ultimately prove valuable to the development of polio vaccines and to the near-extinction of the disease known as “the crippler.”

POLIO’S TRAGIC LEGACY

The late Mark Kalluak was flown from near Eskimo Point in the District of Keewatin (now Arviat, Nunavut) in 1948 for treatment. He was six years old and would not return to his family until he was ten.

Writing in a 1993 issue of Inuktitut magazine, he recalled going from happy and bouncy to drowsy, nauseated, and achy in a matter of hours. “I don’t recall ever being so sick as I was then, tossing and turning and crying my heart out.” He lost all use of his left arm, and his right arm was partly paralyzed.

At the King George Hospital in Winnipeg, he was relieved to meet other Inuit and an interpreter, since he didn’t speak any English. Not long after his arrival, he wrote, staff started preparing to receive more medical evacuees from his home area. But they never arrived.

They were on the plane that crashed in August 1949. Confined to bed, he was taken for daily exercises in a futile attempt to rebuild strength in his polio-weakened limbs. “For me, at least, it didn’t do the least bit of good, and its only result was to annoy me.” Finally, in the spring of 1952, he flew back to the North and home. “Oh, how truly wonderful it was,” he wrote.

Kalluak learned to read and write English during his four years in Winnipeg, and he became a respected translator, teacher, cultural consultant, and author. He was named to the Order of Canada in 1990 and was one of the first recipients of the Order of Nunavut. Despite the lasting damage to his arms and hands, and the separation from his family and home, he concluded his article, “If I had to live my life over I would not choose another path.”

— Nancy Payne

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.