Grey Cup '62: The Fog Bowl

It’s Grey Cup eve in Toronto and the streets teem with loyal followers of Canadian football. They spill out of bars, proudly upholding the Canadian Football League tradition of making merry into the wee hours before the big game.

And a big game it is — the fiftieth anniversary Grey Cup at Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium features a pair of arch-rivals, the Hamilton Tiger-Cats and the Winnipeg Blue Bombers.

Yet, on this Friday night — November 30, 1962 — Canada’s largest city, and indeed, much of southern Ontario, takes on an air of impenetrable gloom. A blanket of fog three storeys high is creeping eerily in off Lake Ontario, shrouding the entire region.

The brume paralyzes communities from Windsor to Kitchener, causing four deaths, and bringing rail, air, and road traffic to a standstill. Driving is so dangerous that even police are ordered off the road, except for emergencies. Criminals, however, are under no such compulsion. Hidden by the haze, they go on a crime spree.

“[The fog] must have given them [the criminals] courage when they thought they couldn’t be seen,” Toronto Deputy Police Chief George Elliot would later tell the Toronto Daily Star.

All of this provided a murky backdrop to the Grey Cup, leaving many fans and players wondering whether the game would go ahead.

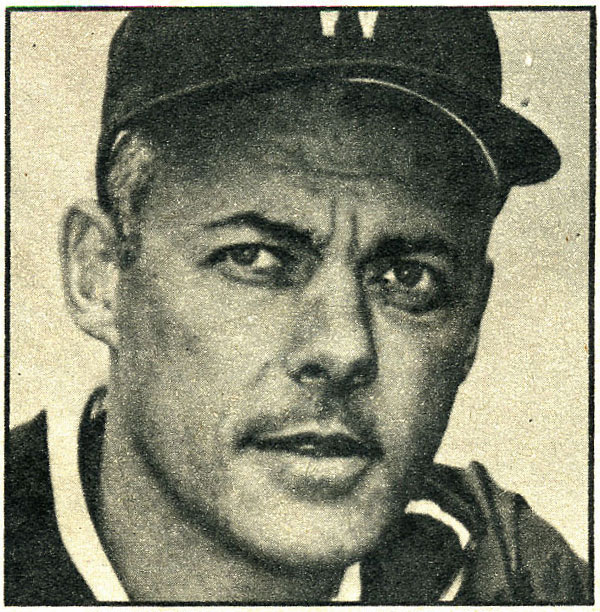

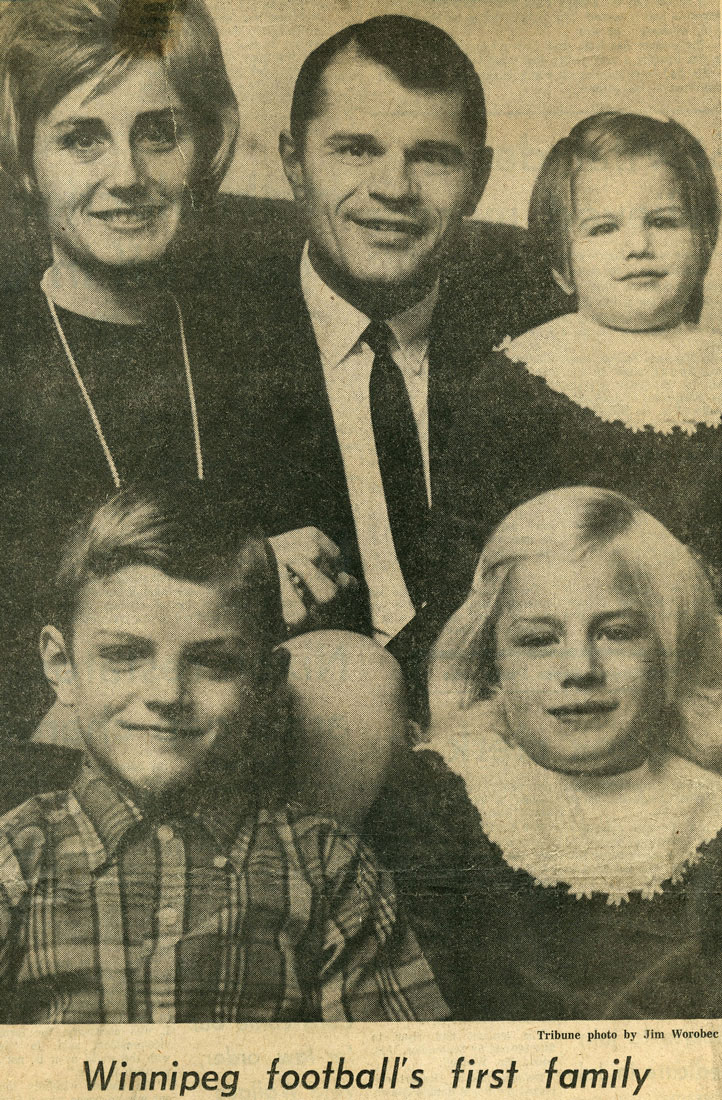

“It was strange and unusual, that’s for sure. We weren’t certain what was going to happen,” recalls Ken Ploen, a principal player in what has since become known as the Fog Bowl.

Now seventy-two, Winnipeg’s former star quarter-back/defensive back jokes that his memory of the game is “kind of foggy at times.”

Foggy. How appropriate....

In the CFL of the 1950s and ’60s, victories were still earned on real grass, under open skies, rendering the game defenceless against the whims of nature. This made for some entertaining championship games. Over the years, fans have been treated to the Mud Bowl (1950), the Wind Bowl (1965), the Ice Bowl (1977), the Rain Bowl (1982), the Snow Bowl (1996), and, of course, the Fog Bowl of 1962.

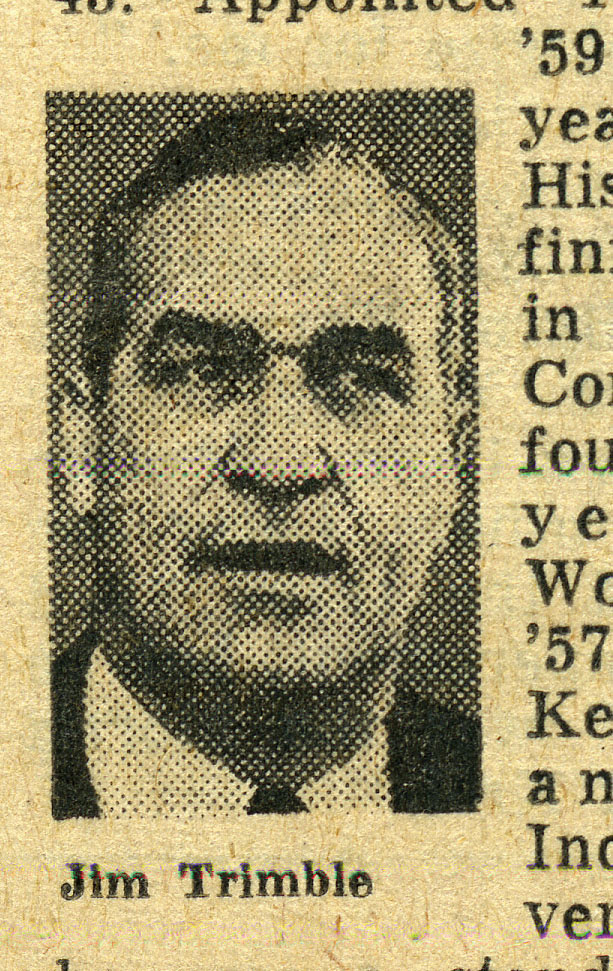

The fiftieth Grey Cup game was the fifth instalment in a heated, sometimes bitter six-year feud between coach Bud Grant’s Bombers and “Jungle” Jim Trimble’s Tiger-Cats. Hamilton captured the 1957 Grey Cup, only to lose to Winnipeg in ’58, ’59, and ’61.

“Yeah, it was a pretty good rivalry,” Ploen recalls, mildly understating the case.

The Ticats’ coach fuelled the fight considerably when, in a snippet of pre-Cup prattle in 1958, Trimble predicted of Winnipeg: “We’ll waffle ’em. We’ll leave ’em with lumps on the front and the back.”

When the Bombers emerged victorious that year, one Winnipeg radio station responded to Trimble’s bombast with a parody of the Kingston Trio hit Tom Dooley:

Hang down your head, Jim Trimble,

Hang down your head and cry.

You know the Bombers beat you,

Now eat your humble pie.

Despite the Bombers’ past dominance, odds-makers in 1962 made the Ticats six-point favourites. The Bombers were limping into the Grey Cup with an injury-depleted roster, the residue of an outrageously demanding playoff schedule that required them to battle the Calgary Stampeders three times in eight days in a best-of-three Western Conference final.

Such a draconian requirement would be unthinkable today, but at the time the Eastern and Western conferences had different playoff formats. With Winnipeg barely able to field a full squad, Trimble once again bragged to reporters that a Hamilton victory was in the bag. And once again, Trimble’s trash talk lit a fire under the Bombers.

“How were we supposed to feel when the man said he could whip us and Calgary on the same day?” Bombers’ defensive end Herb Gray told the Star after the game.

Emotions ran high on both sides as they awaited the scheduled kick-off at one o’clock Saturday afternoon. However, with the fog continuing to roll in off Lake Ontario, the game itself was in doubt until a late-morning inspection of Exhibition Stadium by G. Sydney Halter, the CFL commissioner. The mist appeared to be lifting and Halter made his fateful decision.

“The stadium was clear when we made the decision at 11:00 he would later say. “We had no alternative [but to play].”

In the Bombers’ locker room, everyone was excited and eager to play. Even injured players begged the coaching staff to be let back on the field. For those who couldn’t answer the call, their teammates stepped into the breach. John Michels, the offensive line coach of the Bombers, later described the scene in post-game interviews:

“You know there wasn’t a dry eye when we came out of the dressing room Saturday. Gordie Rowland was sitting in the corner of the room, crying because he couldn’t play and every man on the squad went over and told him they would win it for him. You just knew Hamilton was going to catch hell.”

The fog wasn’t a factor in the first quarter, but by the second quarter the pitch was fading from sight. The thick mist made for some comic moments. At one point, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker got up for a bathroom break and almost walked into a female facility. (The media poked fun at the PM following the game, declaring in a front-page Star story:

“The prime minister couldn’t even find the men’s powder room — with a search party.”) Diefenbaker took the miscue in stride. “I almost made the women’s washroom, under escort,” he later cracked to reporters.

Ploen started the game at quarterback. He recalls the fog not being that bad on the field.

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.

“On punts and long passes you might lose sight, but if you ran the ball it was possible to get things done,” he said.

Then again, he was in the thick of the action. From the fans’ viewpoint, the game was devolving into a confusion of shadows and grunts. They couldn’t see some of the remarkable activity? unfolding beneath the shroud of grey, including a trick play known as a flea-flicker pass between Farrell Funston and Leo “The Lincoln Locomotive” Lewis that resulted in a touchdown.

Mike Hanley, who photographed the game for the Hamilton Spectator and would later go on to become is a Tiger-Cats beat reporter, says the game was one of the “wildest and weirdest” of his career. “I was patrolling the sidelines, trying to photograph a game I couldn’t see,” he recalls.

“It was scary at times, listening to footsteps stampeding toward the sideline, but not knowing if safety could be found by dashing to the left or the right.”

The game itself was a to-and-fro tussle, with the Ticats and Bombers at each others’ boot heels the entire game. All the while, millions of television viewers on both sides of the Canada-United States border stared squinty-eyed at their black-and-white TV sets, adjusting their rabbit ears to no avail.

To an American audience, the Canadian game, with its three downs, extra player per side, and wider, longer field, would in itself have been an odd spectacle. ABC’s broadcasting team didn’t help matters, telling its U.S. audience in the pre-game show that Toronto was situated on Lake Erie (it’s actually on Lake Ontario) and failing to recognize Ploen, Winnipeg’s star quarterback, while announcing the starting lineup.

By the fourth quarter, Halter, the CFL commissioner, had seen — or rather, hadn’t seen — enough. The players were dispatched to their changing rooms while officials discussed what to do next. Both teams were battered and bruised, but the Bombers — at this point leading 28–27 with 9:29 to go — had more to lose by postponing the game. Many of their players were crippled by injuries. Even Ploen had been shifted from quarterback to defence to bolster the lineup.

In contrast, Hamilton’s players were still feeling relatively fresh, and Trimble was lobbying Halter to spot Winnipeg a one-point lead and replay the entire contest the following Saturday. Grant, the famed Winnipeg coach, was desperate to avoid that outcome. He feared his wounded players would run out of steam.

“Why do you think we wanted to finish the game in the fog Saturday?” Grant would later say to reporters. “We didn’t have much left.”

After twenty tense minutes of debate, Halter emerged to deliver his directive: The game would be adjourned until the next day, at which time the teams would battle for the remaining 9:29 of the fourth quarter.

The fans couldn’t believe it. Boos and catcalls erupted from the bleachers.

“Well, that’s just great,” one Blue Bombers loyalist grumbled to the Star. “It cost me several hundred dollars to see this game and I’ve got to go back to Winnipeg tonight without seeing the end of it.”

Others, like Bill Scully of Scarborough, Ontario, rejoiced. “That fog was a bonus,” Scully told the Star following Saturday’s contest.

“Now I can take my boy — some fans from Montreal had to go back and gave me three extra tickets.”

As 32,655 fans began a slow, perilous procession from the stadium, Toronto police were called in to direct traffic. Red accident flares illuminated the haze. Nerves were frayed and frustration pierced the gloom.

In the Bombers’ locker room, the dissatisfaction was as gripping as the fog. “We didn’t think it was going be called off,” Ploen recalls. “We sat in the room, then ... it was pretty disappointing. You know, you’ve got to unstrap the pads, untape ... you wanted to finish what you had started. It was psychological more than anything. You’ve thrown everything you had into it, and now they’re telling you that you had to come back the next day to play nine minutes and change. And the results showed the next day.”

The Sunday crowd was sparse, with less than half bothering to return for the finale. The final minutes were anticlimactic. Winnipeg jealously protected its one-point advantage while Hamilton’s offence was thwarted by bad penalties. Ploen ended up being the last man to touch the ball, diving down to retrieve a Joe Zuger punt just outside the Winnipeg goal line as the clock ticked down. A sixty-minute game that took twenty-four hours and forty-five minutes to complete ended in a 28–27 victory for the Bombers.

Trimble, the Hamilton coach, was furious with the refereeing, calling it “simply preposterous.” His Ticats had racked up thirty-five yards of penalties in little over nine minutes of play. The team’s president, Jake Gaudaur, was equally appalled. “It wasn’t the right way to decide a national championship,” he later snarled to reporters. “I know it sounds like sour grapes, but it wasn’t fair to either team.”

Fair or not, the Bombers were hailed as heroes at home.

“Throughout Saturday’s fog-shrouded drama,” wrote Hal Sidgurdson in his Winnipeg Free Press column, Pigskin Parade, “the Big Blue kept coming back when they should have been finished, kept getting stronger when they should have been weakening.”

In Winnipeg, the city threw a party to honour the team. Manitoba Lieutenant Governor Errick Willis called Grant the best coach in Canada, adding, “He has what it takes to make a rabbit spit in a bulldog’s eye.”

Whether the game should have been suspended is still the topic of debate. Certainly, the fans couldn’t see the action on the field. The Star later summed up the game as “something that looked like blue and black flies chasing each other in a bottle of milk.”

“Looking back,” Ploen says, “the right [decision] was made. The fans up high in the stadium and those watching on TV just couldn’t see. If nobody can see the game....”

And that sums up the Fog Bowl: The greatest game nobody saw.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 4 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

Tempest in a Grey Cup

The game was over. The University of Toronto Varsity Blues had just dispatched the Toronto Parkdale Canoe Club 26–6. Now it was time for the champions to collect their prize — the newly minted Grey Cup.

Oops.

Unfortunately, when then-Governor General Albert Henry George Grey decided to donate a trophy to Canada’s best football team, he overlooked one detail: to commission someone to actually make the Grey Cup. Yes, the now-storied chalice was a no-show for its own baptism on December 4, 1909. It wasn’t until three months later that the U of T received its trophy. The oversight became a quirky footnote in CFL history.

As it was, Grey had not originally intended his cup to celebrate Canadian football supremacy. He wanted his cup to go to Canada’s amateur senior hockey champions, but Sir H. Montague Allan beat him to it. (The Allan Cup is now given annually to Canada’s AAA men’s hockey champs.)

Today, the Grey Cup is the second-oldest North American professional championship trophy, after the Stanley Cup. This season marks the ninety-fifth year of the CFL’s championship game. (While the first game was played in 1908, competition was suspended for three years due to the First World War.) Originally priced at forty-eight dollars, it is now worth in excess of $50,000.

Over the decades, it has been beaten and broken, pilfered and abandoned, held for ransom and held together with tape. The cup suffered its most recent affront after the 2006 championship between the B.C. Lions and Montreal Alouettes in Winnipeg, snapping at the neck during the post-game party.

It has since been welded back together and will be on hand in Toronto this November for the ninety-fifth Grey Cup game. — d.g.d.

Working-class heroes

The term “working-class hero” is something of a cliche, but in the 1960s it aptly described the players of the Canadian Football League. Most held down full-time day jobs during the week, heading for the gridiron for practice after dinner. Weekends were reserved for games.

“One of the benefits of coming to the CFL was that you could pursue a business career,” says Ken Ploen, an all-star quarterback who captured the Grey Cup four times. “That was the big thing. We practised at 6:30 at night, so we could hold down full-time jobs during the day.”

Ploen spent eleven seasons with the Blue Bombers, all the while holding down a second job at MacMillan Bloedell. “If you had a road trip,” said Ploen, “the companies were understanding and accommodating. They’d give you the time off so you could play the game. It worked out real well.”

Ploen wasn’t alone — his teammate, lineman Cec Luning, was known as the Selkirk Milkman. There’s nothing like winning the Grey Cup one day and driving a milk truck the next. Many of the league’s biggest stars did double duty. Russ Jackson led the Ottawa Rough Riders to three Grey Cup titles and was thrice anointed the CFL’s most outstanding player. All the while, Jackson was teaching mathematics full-time. — d.g.d.

We hope you’ll help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past by making a donation to Canada’s History today.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!