Anatomically Incorrect: Bodysnatching in the 19th Century

It is Montreal, deep in the winter of 1862. Griffith Evans, a young medical student at McGill University, is preparing to dissect a human corpse when the calm of the anatomy room is suddenly broken.

Two students burst through the doors lugging a dead body. Evans sees that it is the naked corpse of an elderly white woman. No explanation is offered for this unexpected interruption, nor is one demanded. Everyone knows.

The two students have, as per usual, illegally exhumed the corpse from some unnamed cemetery somewhere — Côte des Neiges, perhaps, or Mount Royal, or maybe even from a distant graveyard in the countryside. Everybody does it, or pays somebody else to do it — even the medical faculty itself. The two body-snatchers are congratulated for unearthing such a fine, fresh specimen, and the corpse is heaved onto the dissection table.

But a problem is on the way.

In walks another student. He looks at the corpse and gasps.

“Good God!” he shouts, “That is my aunt; my cousin, her son, is down below at the chemical lecture and will be up here soon.”

With this, the anguished nephew faints and the dissection rooms falls into a panic. “What shall we do?” one asks.

“Dissect the skin off the face quickly!”

As the nephew is being revived, the two students grab their instruments and immediately set about surgically removing the dead woman’s face. Recording the incident later in his journal, Evans writes that before very long the young dissectors had rendered the subject so completely unrecognizable that when the bereaved son finally arrived, “he went to see the new white subject, cheerfully joked with the dissectors, congratulated them for their successful adventure,” and set about unwittingly dissecting his own mother.

Such were the hazards of morbid anatomy in nineteenth-century Montreal. In truth, the identity of the dead body has always been problematic for human sensibilities. All the feverish turmoil apparent in Evans’s story springs from the central problem that, notwithstanding its lifeless state, the corpse still possesses a certain humanity, an identity, and a dignity — for it remains the embodiment of the living person we have lost.

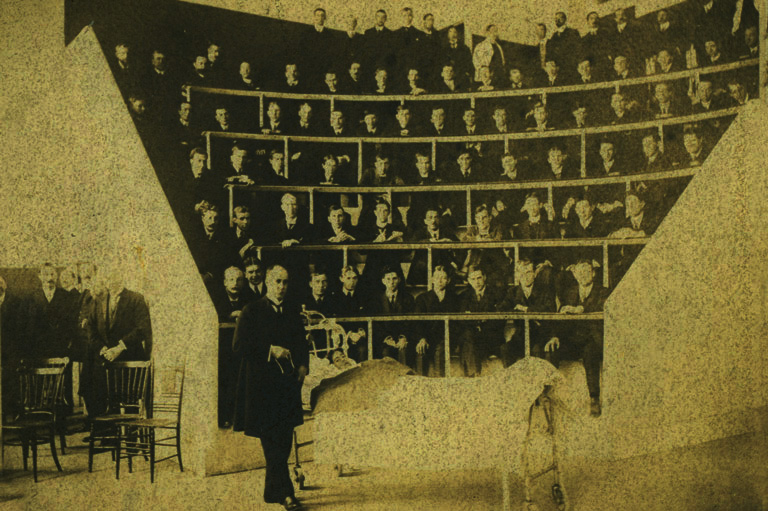

Over the course of the nineteenth century as more and more students enrolled in medicine, and as surgery became increasingly important to the medical profession, the demand for anatomical subjects for outstripped the number that could be legally provided. Taking their education into their own hands, medical students turned to grave robbing, much to the severe distaste of Montreal high society.

How would politicians respond to the needs of the medical schools? Under what circumstances could the stuffy Montreal elite accept that the human corpse could be an object for study and willful mutilation as well as a symbol of sanctity and human legacy? It would be a stubborn and highly confused evolution.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

Indeed, from the very moment it began to evolve in Lower Canada, the anatomist’s vocation had social problems. In the late 1700s, students of medicine could not legally practice without having demonstrated a prerequisite knowledge of anatomy — to be drawn from the dissection of human cadavers was illegal and dissection was punishable as desecration of human remains. As a confounded E.D. Worthington recalled of his student days in the 1830s, “By ‘law’ [the student] was bound to dissect, by ‘law’ he could be punished for dissecting. Strange inconsistency!”

Dissection, therefore, was a furtive business. Medical students burgled graveyards and dead houses of their sepulchral inmates and smuggled them back to the university with a surreptitious wink to the night watchman. In the early days, the “resurrectionists” or “sack-em-up-men,” as they were known, were an artful bunch.

The corpse was exhumed by night, stripped of its clothes and any jewelry to curtail any formal charges of robbery (the corpse itself not being legally designated as private property), and swiftly whisked away. Evans noted in his journal that the best time to snatch bodies undetected was during a snowfall, for the descending snow will obliterate the footmarks.”

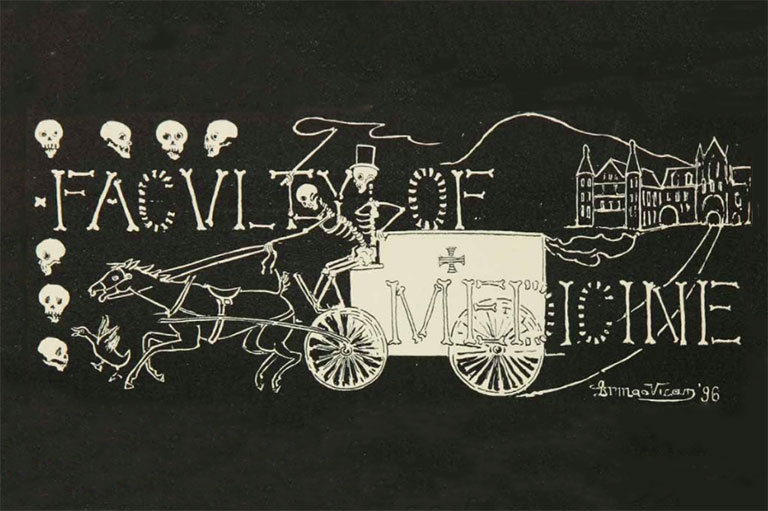

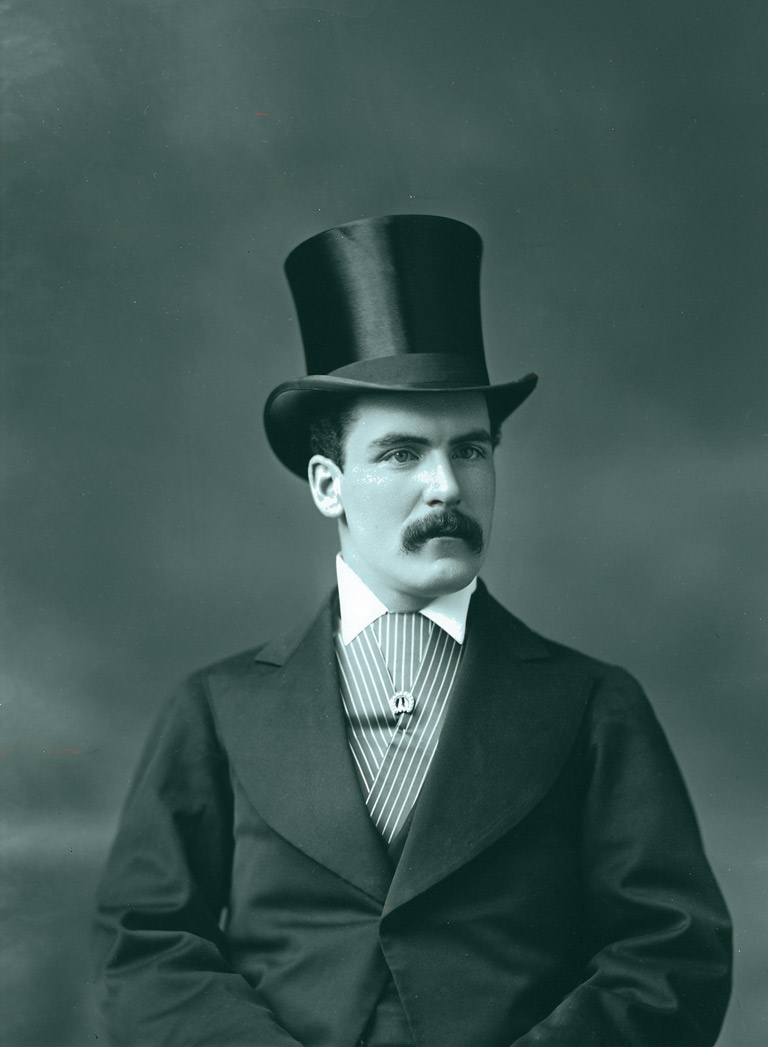

It was not long before the medical schools had created a fairly lucrative traffic in human flesh. Illustrious Montreal anatomist Francis Shepherd claimed in his reminiscences that, by the time he was working as an anatomy demonstrator in the early 1880s, the McGill faculty of medicine was paying body snatchers between “thirty to fifty dollars” per corpse.

French-Canadian students with financial worries were said to pay for their tuition on cadavers, while for the rich Anglo brats from Toronto, grave robbing became a wild, rambunctious rite of passage. As Evans described:

Our English students do it not for economy but for mischevious [sic] fun, dare-devilry, they make themselves intoxicated with alcohol to excite the daring before going to the grave, then they do the work carelessly and in haste and consequently a large portion of them have been traced.

Indeed, that morbid frolic led to some terribly sloppy and conspicuous misadventures. Dr. Shepherd recalled that students burgling cemeteries of Mount Royal would wrap the bodies in blankets and toboggan them down slopes of Côte des Neiges Road.

Occasionally there would be an incident in which the body would tumble out into the street in full view of passersby, and students would have to explain that there had been a fatal tobogganing incident — resulting, suspiciously, in a naked corpse sprawled across the road.

Not surprisingly, such irreverent tampering with the dead would lead to widespread public outrage, especially since anatomy itself was a severely misunderstood profession during the era. Anatomists, surgeons, and dissectors were training themselves to see the body in a very different way from the lay public.

They were taught to intellectually divorce the body from all of its religious, cultural, and even personal meanings, and see the body as simply the anonymous object of their work. This objectivity, or “clinical detachment,” as it was termed, was essential for the practice of surgery.

The annals of history bring forth many incredible triumphs of such objectivity. At the Montpellier Medical School in Europe, one anatomist dissected his own deceased child before a lecture hall full of students. In the seventeenth century, British clinician William Harvey dissected his father and sister post mortem.

Even at McGill — Evans’ farcical caper notwithstanding — such extreme cases exist. Shepherd recalled a French-Canadian student walking into the dissection room to find his uncle on the table. He asked how much Shepherd has paid for the familial corpse, but then willingly dissected it.

Such a radical way of seeing the corpse made no sense to the public at large. To them, this callous disregard for the humanity of the corpse, its spirit, its dignity, and its sanctity, which they saw so grotesquely at play in bodysnatching and dissection, revealed the immoral and possibly murderous nature of the anatomist.

British Canadians in particular were familiar with the dark legacy of William Burke, a Scottish miscreant who, in the 1820s, took to murdering people on the streets of Edinburgh and selling their bodies to the medical schools. Burke was eventually caught, hanged, and sentenced to be dissected in public. The Burke affair naturally became the stuff of legend and cast long shadows of popular distrust upon anatomy, stretching certainly as far as Montreal.

One of the first bodysnatching episodes to inspire civic unrest in Montreal was an incident in Chambly in 1843. The grave robbers had been careless, leaving the body’s coffin and clothes strewn rudely about the tombstones. Worse, they had unwittingly stolen the body of an important person, a well-respected barrack sergeant of the Eighty-Fifth Regiment.

It was a scandalous affair. The police were called and shortly traced the culprits to their seigneury-house-cum-dissection-room only to find the militiaman’s remains already mutilated and heaped in a storage vault.

The outraged Montreal Transcript thoroughly demonized the students — slandering their dissection room as “A Burking House” (Burke’s name has been fashioned into a verb meaning “to commit murder for anatomical subjects”) — and reverently eulogized the soldier’s noble career.

Recounting his sacrifices for the Empire and his many military honours, the paper concluded that “the least the soldier could expect... is that, when consigned to his grave, his remains should lie honoured and undisturbed.”

So it was nearly midcentury. Medical school were growing in size, number, and importance, but the anatomist’s vocation was still outlawed and increasingly despised by the chattering classes.

A group of Montreal physicians began to petition the government. They had to dissect somebody, and if they couldn’t dissect dead soldiers with military honours, whom could they dissect?

After some parliamentary deliberation in Kingston, the Honourable John Simpson submitted an answer: dead immigrants.

It was a shrewd calculation of the conditions under which elite society could tolerate the anatomist’s objective view of death. The public broiled over with indignation when an important member of their citizenry or a fondly remembered relative was dishonoured by the anatomist’s scalpel.

But if the body of some unknown, unmourned person — without family, name, or legacy — were taken to the university and dissected, how could there be a public outrage? Dead immigrants, foreign and friendless, seemed to be obvious candidates.

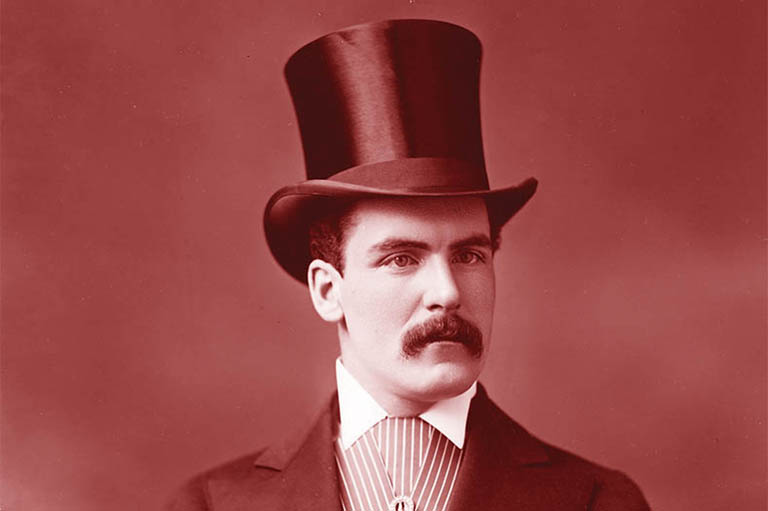

As member for Huron, William “Tiger” Dunlop asked the House, “What harm is done to him or his relatives who will never know it?”

It seemed a brilliant solution, but, all the same, something wasn’t sitting well in Kingston. Mr. Neilson, member of Quebec Country, Upper Canada, sensed a certain vulgarity in Simpson’s bill: “They [immigrants] came here to better their condition — and this is the treatment they are to receive after death?”

Several other members also felt that society’s charitable obligations to the poor and the friendless extended beyond death and consigning their bodies to the dissectors would be immoral. Perhaps only those whom society owed no mercy should be reserved for anatomy.

As member for Toronto Henry Sherwood reasoned, “The bodies of ruffians executed for crimes may be given over for dissection, but to consign by law the poor and the stranger to such a fate!”

Simpson was unmoved. Waving off his critics, the self-satisfied Simpson continually stressed the needs of science and progress.

“Regarding the objections urged,” he quipped in the House, “as well might the alphabet be closed up and men told to become learned.” Simpson found an ally in Dunlop, who was himself a former surgeon.

Dunlop summoned the dark spectre of William Burke into the House. “If you do not allow dead bodies to be used,” he warned, “the living will be taken, for they will be murdered for what they will bring!” Dunlop even made a provocative announcement that he himself would have no objection to having his own corpse dissected — but history can call his bluff: He was buried in a Hamilton cemetery in 1848.

In the end, however, the plan to exclusively target immigrants for posthumous dissection was aborted. There simply wouldn’t have been enough dead immigrants to satisfy the mounting demands of the medical schools.

But there were other friendless people. And after rummaging through all quarters of posthumous society for any and all dissectible persons, the Act to Regulate and Facilitate the Study of Anatomy was passed almost unanimously in December 1843, shortly after the incident in Chambly. It amounted to a veritable showcase for Canadian social rejects.

Following in the footsteps of Britain’s Warburton Act of 1832, the Canadian Anatomy Act proclaimed that the body of any person who died in the care of a government-funded institution was to be handed over to the medical schools unless the corpse was claimed within forty-eight hours, by a “bona fide friend or relative.”

While not explicitly targeting and one group, the legislation made it clear who could be dissected and who could not. Essentially, anyone who relied on charity — the destitute, the insane, convicts, and even children who died in orphanages — would not find their graves on the dissection table.

If the medical schools had a steady supply of dead paupers, it was reasoned, bodysnatching would end, thereby protecting the posthumous bourgeoisie from the indignity of scalpels and sack-’em-up-men.

So much for the Great Equalizer. Just as in life, some dead persons were superior to others. Social peace would be achieved by everyone knowing their proper place, including the dead.

The only problem with Simpson’s legislation was that it didn’t work. If the charities wished to bury their dead instead of donating them to anatomists, they had every right. The 1843 act had no provisions to force their hand or to punish them for interring largely what they did.

As a result, the charitable institutions rendered the legislation almost completely impotent. Finding themselves once again without legal recourse, the anatomists reentered the strange world of the anatomy black market.

Grasping at straws, McGill started to root out bodies by way of some exceedingly weird channels. Francis Shepherd admits to have received a few mysterious subjects, at least one of which was riddled with bullet holes, delivered in rail cars from a “no-questions-asked” type of agent.

Perhaps even more mysterious was a situation recorded in Griffith Evan’s 1862 journal. A group of students snatched a corpse from a country graveyard only to be betrayed by their sleigh man when the bereaved family announced a reward for the body’s recovery.

When the corpse was found at McGill, a humbled board of governors returned it to the family, making great public assurances that from now on they “would not admit any corpse into the dissecting room except through the regular channel.”

This was an empty promise, but Evans explains just exactly what the board meant: “ ‘The regular channel’ is from the United States where plenty of negroes are obtained cheap, packed in crates and passed over the border as provisions of flour.” Evans even adds that it was rare for him to ever dissect a white body during his school days at McGill.

As the century wore on, the vast majority of subjects continued to be furnished by the resurrectionsists, who became increasingly irreverent and sloppy. In 1858, for example, the corpse of the widow of a certain Captain Spillen of His Majesty’s Forty-Third Regiment was audaciously stolen from the dead house of the medical schools’ one institutional ally, the Montreal General Hospital.

The body had, of course, been claimed, and when the funeral party opened the coffin for display, they found not Mrs. Spillen, but instead two sizeable logs of maple wood.

As the Montreal Herald reported, the mourners did not appreciate the ruse: “A shroud was nicely adjusted over the logs of wood, and on the end of them was placed, with cruel ingenuity, the cap of the deceased lady.”

This sarcastic device immediately inspired such a profound and infectious lust for vengeance that before very long a seething mob was stampeding through the city, rooting out the loathesome perpetrators.

Fearing the wrath of this impromptu witch-hunt, the grave robbers dumped the denuded corpse of Widow Spillen into an empty lot on the corner of Ste-Catherine and Guy streets and fled. The English press was indignant.

“The beggar, the madman, the convict, the fallen woman, and the orphan were officially reserved, by law and by force, for the dissection room.”

Perhaps the most notorious bodysnatching caper of the nineteenth century was the robbery of two Roman Catholic nuns from the dead house of a cathedral in Lachine in February 1871. The public frenzy was unparalleled.

The Montreal Gazette, announcing that “there has never yet been related a case of this kind of a more repulsive nature,” was apoplectic with eyewitness reports, interviews with the Lachine townspeople, the sage opinions of the parish priest, furious editorials, and vicious letters to the editor.

Perhaps alarmed by the widespread outrage they had aroused, and finding that no medical school that valued its reputation would dare take the contraband nuns, the thieves panicked and hid the bodies in a snowdrift. But for all their crudeness, these resurrectionists made enterprising use of their hiding place.

As Shepherd chortled, “The bodies were not discovered until a large reward was offered. The perpetrators of the theft were so clever that they only got the reward but were never found out. The affair so scandalized the community.”

“Scandalized” is an understatement. The English newspapers fulminated; it seemed no miracle of surgery could ever redeem the medical students. Awash with hate and hyperbole, the press variously described them as “ruthless,” “heartless,” “ghoulish robbers,” “consummate scoundrels,” and “band of half-drunken and blasphemous students” whose “disgusting transactions” amounted to “atrocity” and “diabolical sacrilege.”

Not taking any more guff after the Lachine affair, an anonymous contributor published this vengeful warning in the Montreal Star on February 11, 1871:

Body Snatchers Beware

We saw to-day a tremendous weapon just finished for the watchman at the Côte des Neiges Cemetery. The fun is of enormous proportions and will be loaded with about eight ounces of buck-shot. Parties meditating a raid on the above place of burial will do well to recollect the formidable shooting iron now in the hands of the wide-awake watchman. A pot shot gang of grave desecrators would most likely supply the dissecting room with enough subjects for several weeks.

Clearly medical students had become inhuman in popular mythology. The Montreal Gazette even alleged on one occasion that they were capable of cold-blooded murder and infanticide. And their notoriety only worsened as the century wore on.

By the early 1880s, bodysnatching incidents were binging out of control. Between December 1882 and March 1883, medical historian D.G. Lawrence counted twenty-six reported episodes of grave robbing, and Montreal was fuming. Politicians soon realized they would have to intervene once more.

Pressured by the opposition and the medical community alike, the Conservative government of Premier Joseph-Alfred Mousseau finally passed renewed anatomy legislation with the Anatomy Act of Quebec on March 30, 1883. The act effectively served to reinforce and empower the 1843 legislation with coercion and punishment.

And medical schools that acquired bodies from any source but the municipally elected anatomy inspector would be fined as much as $200, and any government-funded charity that refused to hand over its unclaimed dead would have to pay the same amount.

The act also made it a lot harder to claim a body. Now they would have to be claimed within twenty-four hours instead of forty-eight, and only by relatives, not friends. Perhaps as a token gesture, the act required that Protestant and Catholic remains be separated and “decently interred” after dissection — so at the very least the pauper dead were afforded some modest religious rights.

But the beggar, the madman, the convict, the fallen woman, and the orphan were now officially reserved, by law and by force, for the dissection room. As for the pious nun, the beloved widow, and the illustrious soldier, the legislation tucked them soundly in their coffins for eternal repose, with reverence and honour.

The Quebec Anatomy Act was a resolute success, There was virtually no public opposition and most charities were successfully covered. The St. Patrick’s Orphan Asylum, however, objected and freed itself from being legally bound to the act by giving up its government grant, but it was speedily brought to justice.

But despite these isolated cases, the Canada Medical and Surgical Journal could announce in March 1884 that not a single case of grave robbing had been reported in Quebec that winter; “The requirements of the Medical Schools,” the journal declared, “have been amply met.” And with that the dark arts of bodysnatching were lost to the mists of time.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!