Voyageurs on the Nile

-

Manitoba voyageurs at Quebec, before embarking for Egypt on the Ocean King. The contingent from Manitoba extends to the right as far as the sailor. E.B. Haight is seated beneath the bow with another’s hands on his shoulders. Col. Kennedy stands in the centre.I. Martial

Manitoba voyageurs at Quebec, before embarking for Egypt on the Ocean King. The contingent from Manitoba extends to the right as far as the sailor. E.B. Haight is seated beneath the bow with another’s hands on his shoulders. Col. Kennedy stands in the centre.I. Martial -

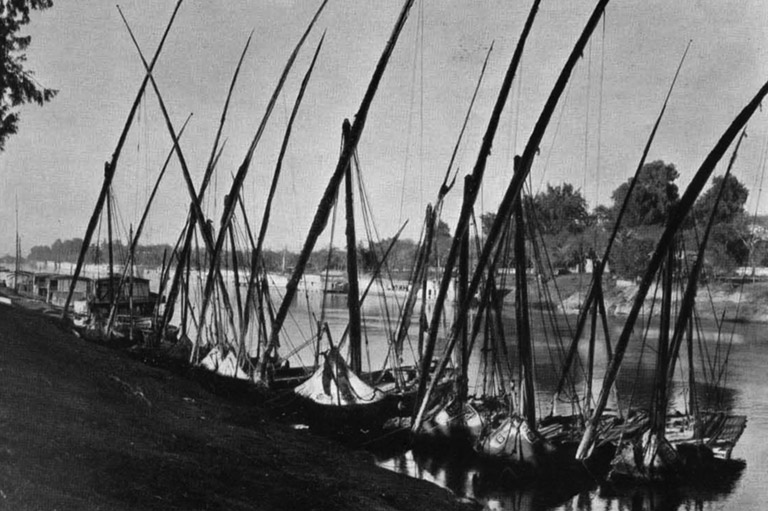

Nile boats at Cairo.Canadian Pacific Railway

Nile boats at Cairo.Canadian Pacific Railway -

-

One of the fleet of whale boats which the Canadian voyageurs tracked up the cataracts of the Nile.

One of the fleet of whale boats which the Canadian voyageurs tracked up the cataracts of the Nile. -

Capt. E.B. Haight, wearing his Egyptian campaign medals.From the portrait by Kathleen Shackleton

Capt. E.B. Haight, wearing his Egyptian campaign medals.From the portrait by Kathleen Shackleton

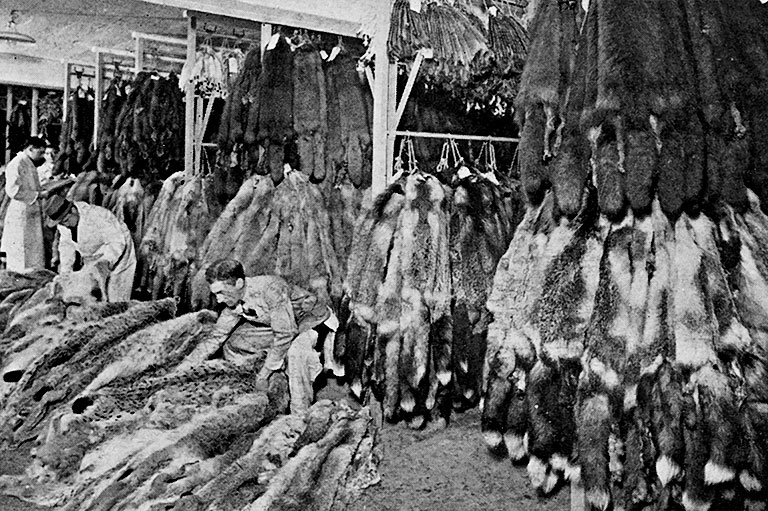

Canada’s contribution to the Egyptian campaign of 1884-5 was a force of three hundred and seventy-seven volunteers. Drawn from logging camps and the rivers throughout the Dominion, they were picked men, thoroughly fit and experienced in handling river craft of all kinds. The “Voyageurs,” as they were generally called, attracted much attention during the period of their service, and when disbanded were highly praised for the manner in which they had performed their arduous duties.

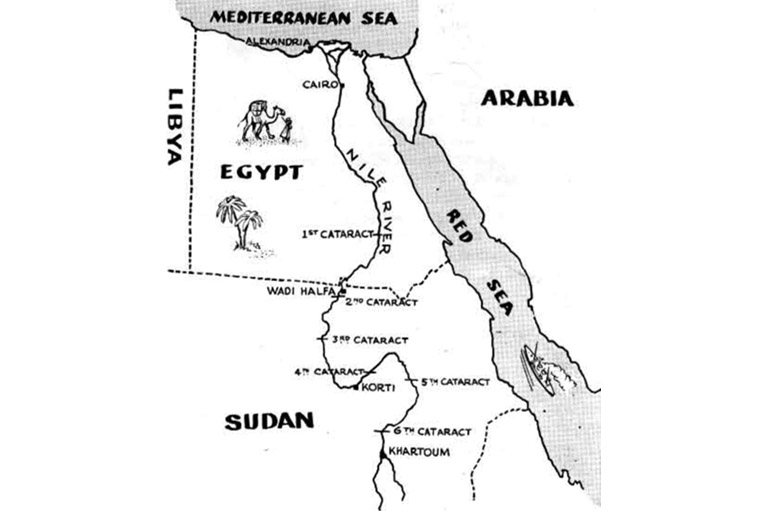

It is unnecessary to dwell at length on the events which led up to the campaign. When the Canadian contingent was organized, the course of the war was directed to obtaining possession of Khartoum, where General Gordon was beleaguered, and inflicting a crushing defeat on the hordes of fanatics who, controlling the Sudan, menaced the peace and welfare of the entire country. To achieve this object, it was necessary to transport troops and munitions by boats for a great distance up the Nile, which was very difficult to navigate for many miles of its course by reason of large cataracts and smaller rapids. The native boatmen familiar with the river were slow of action in emergencies, and not altogether trustworthy by reason of religious affiliations with the dervishes.

Lord Wolseley, who had commanded the Red River Expedition of 1870, is credited with the decision to employ Canadians as boatmen. He had taken charge of the campaign at a time when haste was a paramount necessity. A cablegram was dispatched to his old friend and orderly officer of the Red River campaign, Colonel George T. Denison, asking him to recruit a force of river-men such as had won his admiration in the past.

Colonel Denison acted quickly, and with able assistants enlisted men throughout the Dominion. At Winnipeg he was helped by the Commissioner of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Herbert Swinford, then in charge of the Company’s transport at Grand Rapids, actively assisted. A number of the men engaged had worked for the Company on the rivers of Western Canada, and they belonged to a type no longer required by modern conditions.

Suitable men were quickly obtained and a contingent went east under Captain James Kennedy, a brother of Colonel Kennedy of the 90th Winnipeg Rifles. They were engaged for a period of six months, with the possibility of re-engagement at the end of that time for a further period of service. The rate of pay was high—five dollars a day with uniforms and rations furnished. The uniform was grey with a large felt hat. The men recruited were assembled at Quebec and embarked on the S.S. Ocean King.

The contingent arrived at Alexandria in Egypt on October 7, 1884. To men from the forests and rivers of Canada, this strange city was enchanting. There was something entirely new to them in the dazzlingly white buildings masking a network of alley-ways and slums. There were more people than they had ever before seen—people wearing strange flowing garments and red tarbooshes, with here and there a green one denoting the proud Hadjii, who had pilgrimaged to Mecca.

As men acquainted with rivers, they gazed in critical wonder upon strange craft—xebecs, mahones, feluccas and caiques, gaudy of sail and richly coloured of hull. Then, without loss of time, they began a long journey by train and boat to the scene of their labours.

Past Cairo, the pyramids, and the activities of the great delta, and through the long strip of verdure bordering old Father Nile which is Egypt. Through a land of rice and cotton fields, lush pastures, olive groves and date palms. Past walled villages enclosing flat-topped houses, white and blue under the scorching Egyptian sun, where the people lived their little lives as in the days of the Pharaohs. Here were dark-skinned fellaheens labouring with primitive ploughs drawn by patient oxen or water buffaloes; there laughing girls clad in voluminous white and blue robes, balancing huge water pitchers upon their heads.

Water-wheels clanked, and the pump of old Archimedes revolved endlessly, pouring water into the canals which rendered fruitful the ever-thirsty soil. Around all were groups of playing children and swarms of naked, velvet-skinned infants. Overhead wheeled flocks of snowy pelicans, reminding the prairie men of home, chattering paddy birds and flocks of doves, with myriads of migrant birds from northern climes. And far away, to either side of the verdant strips, were the yellow, ever-moving sands of the desert.

The river, too, held much of interest to our voyageurs. There they saw snowy dahebeeahs, towering and slim of spar, great sailed gayasses sweeping up and down stream equally well, and grotesque nuggars, like half walnut shells, carrying ridiculous masts. As they heard the age old chant of the Nile boatmen, Hoop ya ragil, hoop bel affia—hoop heli, heli; hoop bel Nebi Sagh, they perhaps chuckled over the fact that the Sirdar considered the chanson and shout of the western infidel to be more potent in subduing the spirit of the rapids.

At last Wadi Haifa was reached. Here was great activity, for infantry, engineers, artillery and cavalry were preparing for a great advance under Wolseley. Here also was the materiel of war so urgently required by the column which was to advance on Khartoum, nine hundred miles away.

Now, for the first time, the Canadians saw the boats, to handle which they had travelled so far. The craft were of the whale-boat type and had been built to the orders of Col. (later Sir) William Butler, who had served under Wolseley in the Red River Expedition, and who was now in command of the boats.

Clinker built, carrying sails and twelve oars, they were about thirty-two feet in length, with a beam of seven feet and draft of thirty-two inches. They could carry loads up to 6,500 pounds. The only thing about them of which the voyageurs disapproved was the keel, for they considered keelless boats easier to handle in white water; but this objection was soon found to be groundless.

It was intended that two boatmen be in charge of each, one a native reis and the other a Canadian; but this arrangement did not last long, for the westerner soon proved that he was far more capable of handling the boats than his Egyptian confrère. It was found also that, while it required a full day for fifteen to twenty natives to take a boat up a rapid, seven Canadians could do the same job in two hours. The round trip from the foot of the first rapid to the head of the fourth and return to the base required one hundred days.

It was soon seen that the task was not so easy as it had at first appeared, but, day after day, under a blazing sun, the work progressed. Imperial troops, marines, and bluejackets worked with a will. Wolseley, in his letters, is rather scornful of the efforts of the deep-sea sailors to handle the whaleboats in a rapid, and his sentiments were seconded by Butler. But finally the back of the job was broken, and the whole force of voyageurs was no longer required.

Though their period of engagement had expired, it was necessary to retain a certain number of them, so eighty-nine men renewed their engagement. Before that, however, Major General Brackenbury had reviewed the river column at Korti. Drawn up under a flagstaff, two thousand men were thanked for their strenuous work and especial praise was accorded to the Canadians for their share of it.

A sidelight on the Canadians’ part in the campaign can be found in a letter written by Lady Wolseley to her husband on November 6, 1884. Referring to reports cabled to the London Standard by its correspondent at the front, she writes: “His telegrams are full of the difficulties of the expedition. How the Canadians say the cataracts are much worse than they expected; how we must expect much drowning; how it is hard to have no spirits given them after the very hard work they do.” Evidently the old fur-trade “regale” had no place in the Sudan.

Of the three hundred and seventy-seven men originally comprising the force, ten gave up their lives. Of these six were drowned in the waters of the Nile. For their services the Canadians were awarded the British war medal and, in addition, the Khedive’s star. There are but few living today who are entitled to wear the blue and white ribbon, but one of them still lives in Edmonton. He is Captain Ernest B. Haight, who served the Hudson’s Bay Company from 1882 to 1931 and was for many years one of the best known figures on the waterways of the great northwest.

It is from his reminiscences that much of the material for this article has been gathered. Captain Haight’s days of activity are past; but he still likes to talk of his experiences in the old fur trade, and of his year abroad when he was a voyageur on the Nile.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!