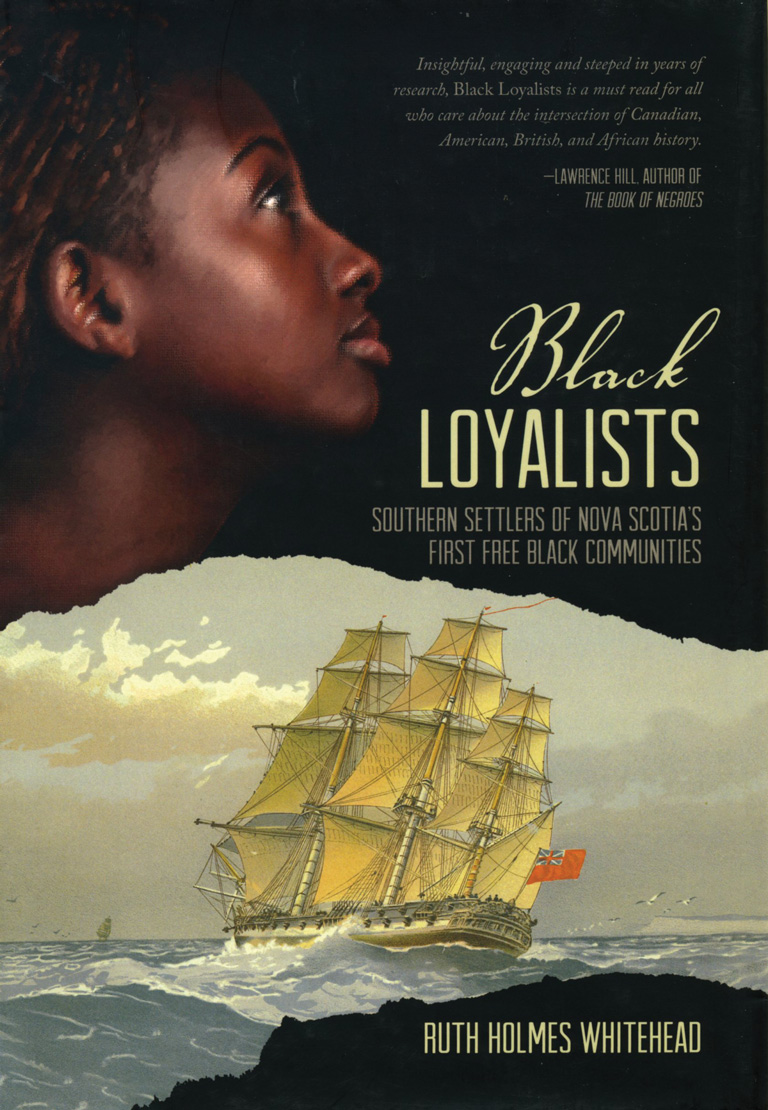

Black Loyalists

Black Loyalists: Southern Settlers of Nova Scotia’s First Free Black Communities

by Ruth Holmes Whitehead

Nimbus Publishing

272 pages, $29.95

The reality of slavery was brutal, degrading, and inhuman: Slave owners routinely beat, whipped, maimed, and killed their human chattel; female slaves faced added abuses, including routine rape and forced childbirths in order to save their masters the costs of purchasing additional slaves.

Most slaves who attempted to escape were captured, sadistically punished, and sometimes killed. But a few did obtain their freedom, including the men and women who sided with the British during the American Revolutionary War.

In Black Loyalists: Southern Settlers of Nova Scotia’s First Free Black Communities, historian Ruth Holmes Whitehead offers a finely crafted and carefully researched glimpse into the lives of slaves who fled the fledgling United States as Britain’s last stronghold, in New York, began to crumble. Boarding ships, more than 2,700 black refugees fled New York for Nova Scotia, at the time a bastion of British naval strength.

These Black Loyalists were promised rich land for farming and for settlements, but the reality was off the mark. The land was generally rocky. New land grants were slow in coming. And, while slavery was illegal in Nova Scotia, racism persisted. Eventually, more than one thousand Black Loyalists left Nova Scotia for the west coast of Africa. Arriving in modern-day Sierra Leone, they established the community of Freetown.

Whitehead’s narrative draws heavily on information found within the Book of Negroes — not the award-winning 2007 Lawrence Hill novel but the original ships’ registry created in 1783 to record the names and particulars of the Black Loyalists who fled New York for Nova Scotia.

Whitehead, a research associate with the Nova Scotia Museum, writes with an academic’s rigorous attention to detail, but also with a storyteller’s flair. Her prose is bluntly honest. For instance, when writing about the practice of collecting bounties on runaway slaves, including higher prices for dead slaves, she labels it for what it truly was: “murder” for money.

Black Loyalists is divided into three sections, and of them I found the opening section on the early history of the slave trade to be the most fascinating. Drawing on primary sources and slaves’ own narratives, the author paints a picture of an American society sick with moral rot. One can’t escape the hypocrisy of slave owners drawing on Biblical passages to justify slavery, nor can one forget that America — founded on principles of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — was quick to deny these basic human rights to anyone with the “wrong” skin pigment.

While “white masters” are the historic face of the slave trade, Whitehead reminds readers that the business of slavery also relied on middlemen in Africa who eagerly captured their fellow Africans and sold them to the white slavers based along the African coast.

She also notes that American slave owners enslaved more than just Africans. They also captured local Aboriginal peoples of the southern United States and put them to work on plantations. However, Aboriginal slaves were quickly decimated by smallpox and other foreign diseases carried to American shores by European trading ships, including the very vessels that brought black slaves to the colonies. With thousands of Natives dying from disease, it became too much trouble for slavers to find healthy Aboriginals to capture. And so they turned their focus exclusively to the African slave trade.

Black Loyalists is a good primer for readers who want to learn more about Canada’s place in the centuries-long effort to eliminate slavery. It’s also a great background text for fans of Hill’s Book of Negroes novel. Black Loyalists reminds us that the story of Canada is far more complex and diverse than the typical English-French and Aboriginal-colonizer narratives taught in grade school, and that “American” and “Canadian” histories are more tightly entwined than we generally realize.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

With 7 uniquely curated newsletters to choose from, we have something for everyone.