Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Roots: Of Family Trees and Root Causes

Many Canadians reckon that family historians are odd, if not outright weird. I’ve even heard it said — by a prominent person, no less — that an interest in ancestry signifies a narcissistic personality. Droll, but surely that can’t be the entire story. It doesn’t explain why so many of the recently retired, who haven’t thought about their origins in decades, take up family history in their later years. They can’t all be eleventh-hour egomaniacs. Why do these people feel bound to study their family trees?

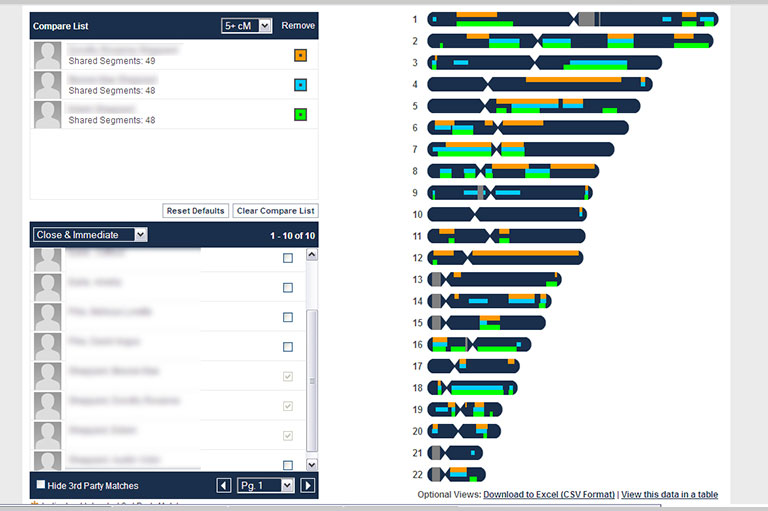

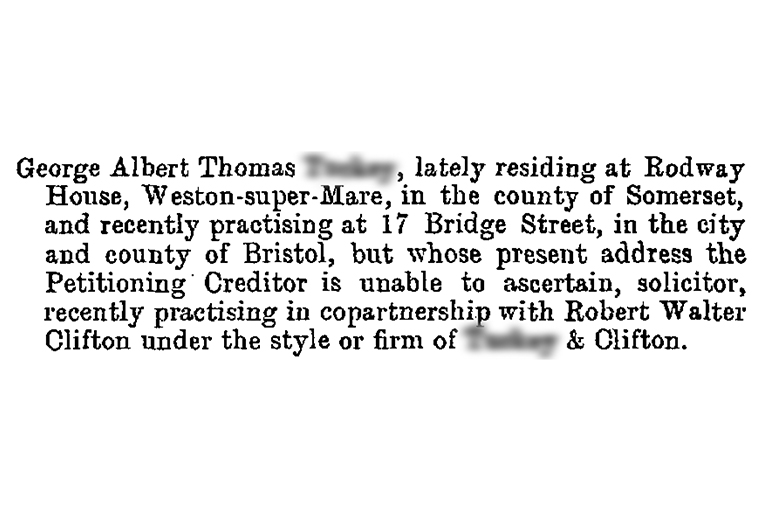

For years I was aware of just two kinds of genealogists. One group, often described derisively as “name collectors,” includes people who are happy to judge their success by the comprehensiveness and antiquity of their lineages. Over time I’ve come to respect name collectors in direct proportion to their competence. It is a delight indeed for a researcher to discover shared ancestry with an expert practitioner of a name-collecting bent. Their work, if verifiable, can save others a lot of effort.

Even so, I’m not a name collector, and I don’t think most genealogists are. I couldn’t give a fig if my triple-great-grandfather was an Albert or a Herbert, or whether he was born in May or December, except insofar as these bits of information contribute to the robustness of my real research. For me, it’s all about the family stories. Can they be confirmed or rejected? How did our ancestors’ lives intersect with major historical episodes (for example, a Tommy in the trenches, the survivor of a pogrom, missionaries during the Raj)?

For her 2019 book Roots Quest: Inside America’s Genealogy Boom, sociologist Jackie Hogan injected academic rigour into the question of why people take up genealogy. She conducted in-depth interviews with more than seventy amateur and professional genealogists, then analyzed the results and grouped their motivations into four categories: “mystery” (for instance, a love of discoveries or of the puzzle), “identity” (knowing oneself by knowing one’s ancestors), “duty” (a responsibility to memorialize our ancestors for posterity), and “connection” (bonds to family and the wider community).

I recently conducted a qualitative survey with more than forty participants from my local family-history Facebook group. Their comments confirm that Hogan’s four categories do indeed encompass most researchers’ experiences. In practice, though, many of us are complicated and find motivation in various ways at different times.

To my biased eye, these studies show more altruism than narcissism in the makeup of family historians.

Consider the case of survey participant Cathy. As a child she saved an old photo album from being tossed into her grandmother’s furnace. Later in life, Cathy wondered about the lives of the people in the photos and set out to discover more. Today her interest is sustained by contact with others who are researching the same ancestors. What started as duty matured into a passion through a love of mystery and thrives today through connection to other like-minded souls.

To my biased eye, these studies show more altruism than narcissism in the makeup of family historians. Solving mysteries, remembering the dead, forging bonds with family — these are not the pursuits of the emotionally stunted. Even name collectors seeking ancient connections to royalty are more in it for the fun these days than for any expectation of social advancement.

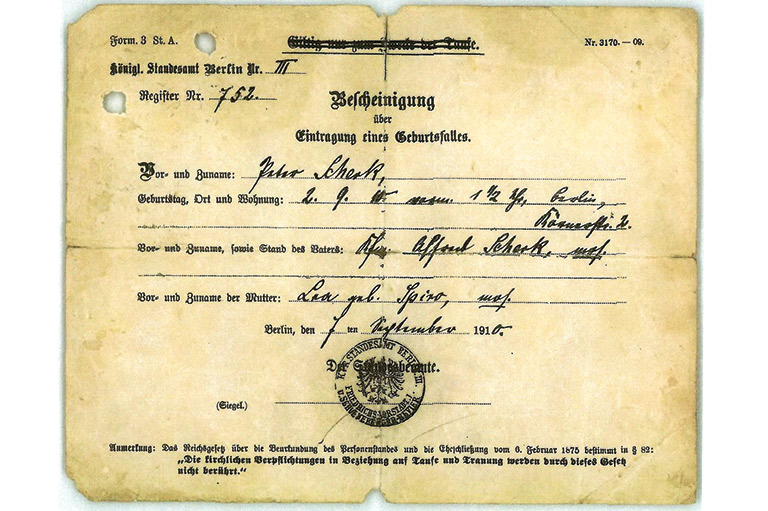

One motivation that doesn’t fall neatly into Hogan’s paradigm is an enthusiasm for lifelong learning. Scarcely a day passes without an opportunity to pursue a subject that is only peripherally related to my genealogical interests. Here’s a fresh example arising from my most recent column (“Lost – and found!” in the December 2020-January 2021 issue of Canada’s History). In the course of a lengthy exposition about the search for a birth certificate, I referred to the Jewish grandparents of a friend as having been “executed” by the Nazis. I was not aware until reading a letter from a reader that there is an issue with the word “executed” in this context. Scholars now favour the rejection of terminology that might connote the legitimacy of the Nazi state; after all, it routinely breached the most basic tenets of international and natural law. Accordingly, a word like “executed,” which implies at least a veneer of legality and due process, should give way to more precise language. If you read the online version of that column, you will find that “executed” has been replaced by “murdered by the state.”

I could cite a hundred similar (though more trivial) pieces of valued learning I’ve acquired in my genealogical travels. In a memorable passage from Hogan’s book, she draws a parallel between teenagers watching zombie movies and grandparents researching their ancestry. At opposite ends of their lives, teens and grandparents have hugely different experiences and expectations of the dead. As you get older, you may not see dead people, but you can definitely have a conversation with them. It’s lifelong learning at its best!

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!