Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Arctic Visions

Skip to the bottom to watch the trailer of Romance of the Far Fur Country and the full length video of Nanook of the North.

On March 30, 1915, long before he became famous, Robert Flaherty was at Convocation Hall in Toronto, exhibiting a series of motion pictures taken of the Inuit near Baffin Island. In the audience, a reviewer kept his eye on one man, who, he observed, brandished “an occasional enormous yawn” while igloos and scenes of Inuit domestic life flickered in front of his eyes.

The man was Sir William Mackenzie, the railroad magnate who was at that time exploring the feasibility of a rail line to move prairie wheat to Hudson Bay, from where it would be shipped to Europe. Mackenzie was also Flaherty’s employer.

Robert Flaherty would win acclaim seven years later for his film Nanook of the North, but on that spring evening at the University of Toronto campus he was still a prospector hired by Mackenzie to find minerals that a future rail line could carry back from Hudson Bay lands the film footage, gathered while searching for ore deposits, focused on Inuit families in their day-to-day lives, whether eating breakfast or lighting oil lamps.

Penniless, and recently married to Frances Hubbard — who would become his lifelong collaborator and play a huge role in his success — Flaherty hoped the northern footage would be enough to convince Mackenzie to bankroll another trip north — his fourth.

Despite Mackenzie’s yawns, the railroad man must have been impressed. Not only did he fund another expedition, he offered Flaherty an office in which to finish the film when he returned in september 1916. Flaherty cut and assembled his footage in the makeshift studio, preparing the final copy to send to New York in the hope of finding a distributor.

The negatives were in stacks and the extremely flammable nitrate film was wound tight on reels when the tobacco-smoking filmmaker made a catastrophic mistake: “Carelessly, amateur that I was, I dropped a cigarette off the table,” Flaherty recalled.

The small office ignited instantly. Rushing into the street with his clothes on fire, the filmmaker barely saved himself. He was so badly burned that he spent weeks in hospital. As for his 30,000 feet of original film, none of it survived. He was left with a single print, in poor condition.

Disheartened, but not defeated, Flaherty travelled to New York, hoping to sell the Baffin Island print to someone willing to transfer it back to negative, an expensive process. To garner attention, he screened the print wherever he could. In 1918, he showed it to the New York Geographical society, where he had a moment of realization.

Watching many of the same scenes that Sir William Mackenzie had sat through three years earlier, Flaherty began to cringe. “It must have bored the audience to distraction,” he said later. “It certainly bored me.”

Bruno Weyers was in the audience the night of Flaherty’s epiphany, and he wasn’t bored at all. Weyers, the Hudson’s Bay Company agent for New York, was so taken by the film that, with the HBC’s 250th anniversary just two years away, he suggested borrowing the footage for the festivities.

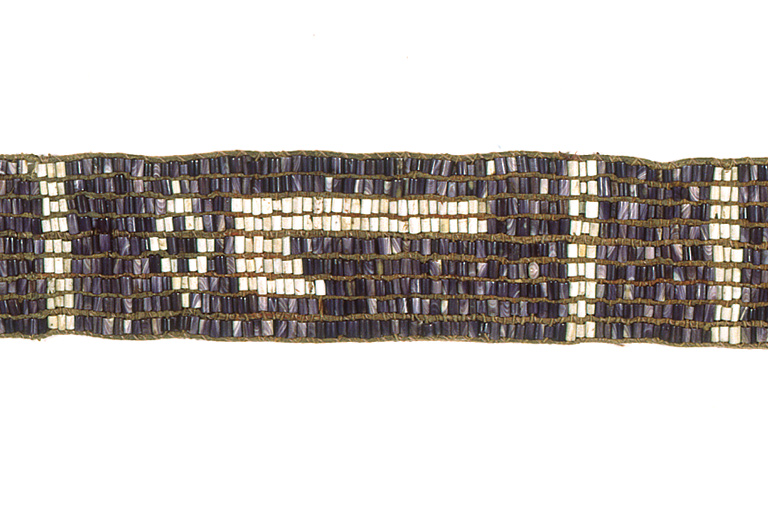

Various anniversary commemorations were already underway, including a written history of the company, a gramophone recording of that history, and the inauguration of The Beaver (now known as Canada’s History) magazine.

The biggest gathering was slated for Winnipeg, the company’s Canadian headquarters. the main attraction was to be a film depicting HBC activities in the North.

But rather than using Flaherty’s footage, the HBC decided to shoot its own film. Flexing its corporate muscle, the HBC bought controlling interest in a film company in New York and selected H.M. Wyckoff, a former cameraman for the Red Cross in Russia, as chief cinematographer for the “moving picture expedition,” as the HBC called it.

At Wyckoff’s disposal was the Nascopie, an HBC steamer. With film gear and crew on board, the Nascopie shoved off from Montreal in July 1919 with Captain George E. Mack ferrying them into Hudson Bay.

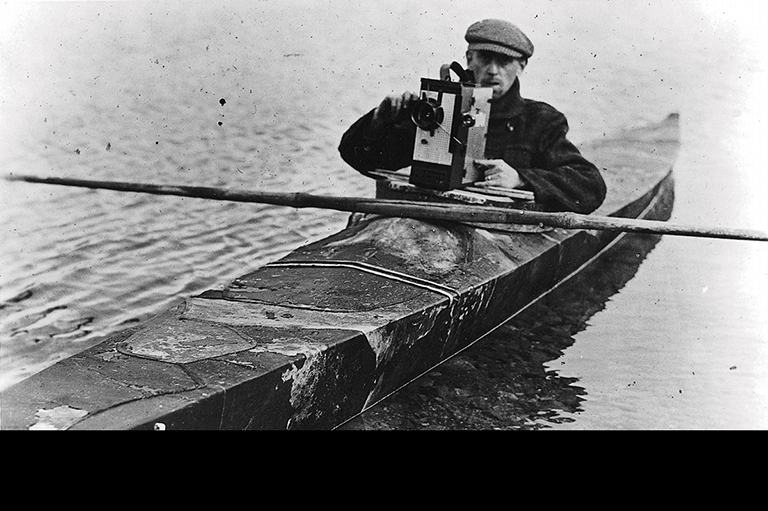

Wyckoff shot film while docked at trading posts, from the Nascopie deck, and sometimes even from a canoe or kayak. Using the technology of the time — a hand-cranked camera, black-and-white film, and no sound — he recorded fur trade life: the unloading of crates emblazoned with the HBC emblem; trappers trudging down traplines; fishermen hunched over holes in the ice; and even a marriage ceremony.

By the time Wyckoff completed filming at the end of December, he’d gathered 75,000 feet of film, some eighteen hours of viewing time. he rushed the negatives to New York where the editing began. By mid-April, a first draft clocked in at four hours. A month later it was cut in half.

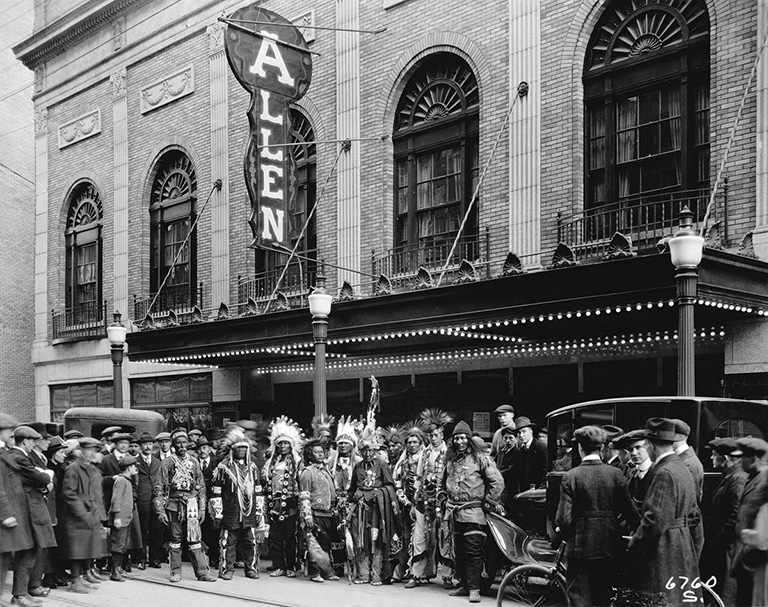

The completed film, entitled Romance of the Far Fur Country, premiered on May 23, 1920, at Winnipeg’s illustrious Allen Theatre.

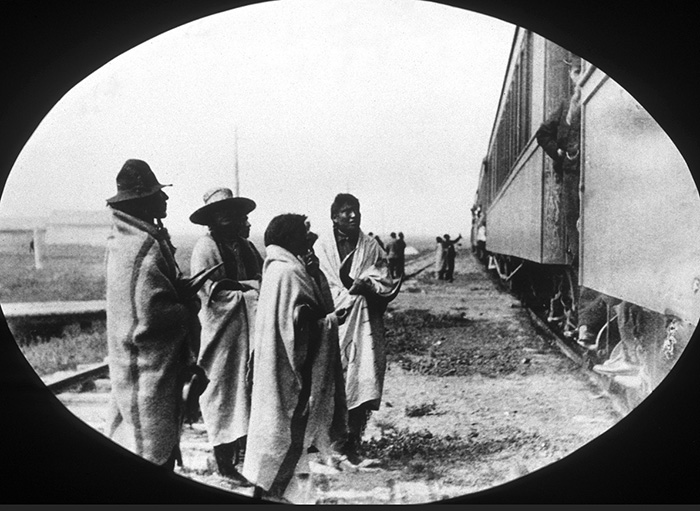

The crowd was a mix of HBC store clerks, shoppers, and a hundred First Nations people in traditional clothing. The latter were unfamiliar with European theatre-going etiquette and interacted with the motion pictures, calling out “get your gun” or “shoot him” when animals appeared on screen.

It eventually played in London, where footage of white women models wearing HBC beaver fur coats was spliced into scenes on a trapline, a not-so-subtle reminder of the company that funded the film.

Robert Flaherty was still in New York when Romance of the Far Fur Country premiered in Winnipeg. By then he had stopped peddling the Baffin Island print. He was preparing instead to reshoot the footage lost in the studio fire. This time, though, he was not going north as a mineral explorer, but as a full-time filmmaker.

Thierry Mallet had been to one of Flaherty’s screenings. As president of the New York branch of Revillon Frères, a rival fur company to the HBC, Mallet was gearing up for an anniversary, too — Paris-based Revillon was celebrating two hundred years in business.

Taking a page from the HBC, Mallet put Flaherty on a salary to produce a promotional film capturing the essence of the company, “one better than the recent anniversary of their rival,” Flaherty noted. Flaherty could then cut his own film from the same footage.

In June 1920, Robert Flaherty left New York for a fur trade post at Port Harrison, on the shores of Hudson Bay.

He arrived in early August, his thirty-nine crates of film gear barely escaping a dunking when the barge they were being transferred to almost sank in foul weather.

Revillon Frères gave him a comfortable cabin with flower-print curtains, where he kept a gramophone, hung portraits of his heroes on the walls, and stored 75,000 feet of film stock. A ramshackle addition, tacked together with scrap lumber and driftwood, served as his developing room.

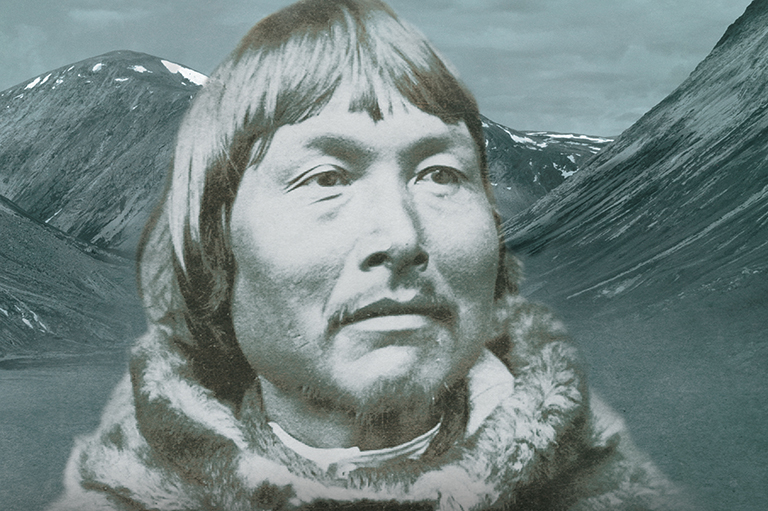

Flaherty gathered a dozen local Inuit for his film crew. He chose a main character, a well-known hunter named Allakariallak — who would be known in the film, and for posterity, as Nanook (which means polar bear in Inuktitut).

Nanook also served as his developing room assistant. Other characters included Nanook’s wife, Nyla, and the couple’s young children.

Flaherty wanted to ensure that viewers of the film stayed awake, so he strove for plenty of action and suspense. He demanded complete creative control, especially during hunting scenes.

“Do you know that you and your men may have to give up making a kill, if it interferes with my film?” he asked Nanook. His film star responded dutifully: “Not a harpoon will be thrown until you give the sign. It is my word.”

Nanook’s promise was tested during a walrus hunt on September 26. Though Nanook admitted it had been “many moons” since he’d hunted the animal, he followed Flaherty’s orders, harpooning a two-thousand pound monster while it slept on the beach.

Rudely awoken, the walrus wrestled itself into the sea and a dangerous tug-of-war ensued. As the frightened men slid toward the icy waters, “the crew called to me to use the gun but the camera crank was my only interest then and I pretended not to understand,” Flaherty said later.

After developing footage, Flaherty often held public screenings, projecting his moving pictures onto a Hudson’s Bay Company blanket hung in the kitchen of the fur post.

At the walrus hunt screening, the audience members, many of whom had helped film the scene, were enthralled as Nanook and his crew struggled for footing on the beach. “Every last man, woman, and child in the room was fighting that walrus,” Flaherty said of the screening.

Flaherty shot through the long, dark winter, except when it was so cold that the film would shatter into tiny particles the moment he turned the crank. Much film was lost to soot, the result of using soft coal to heat the stove in the film-drying room. still more film was lost due to stray hairs from Nanook’s deerskin coat.

On April 29, 1921, Flaherty’s developing hut caved in, a major frustration as processing film on-site was no small feat: “The light of my little electric plant was not steady enough for the printing of the film,” Flaherty wrote in his journals.

“To do that, I cut a hole in the wall of the hut and let the daylight in through a trap the exact size of the aperture of the printing machine.”

“He told me he was terribly sorry, but it was a film that just couldn’t be shown to the public.”

By the end of September, Flaherty was back in New York, putting his film together. The final version made little reference to the fur industry, nor to his sponsor, Revillon Frères, other than in the credits. The company was by then losing money and had started selling its fur posts to its rival.

By 1936 the HBC held full control of Revillon Frères. As for the promotional film Flaherty was supposed to make for Revillon’s 200th anniversary, it seems to have been discarded.

Flaherty’s own film appeared destined for the same fate. His first screening was for the staff of Paramount, a potential distributor.

With the projection room a haze of cigarette smoke, the manager “very kindly put his arm around my shoulders and told me that he was terribly sorry, but it was a film that just couldn’t be shown to the public,” Flaherty said of the event.

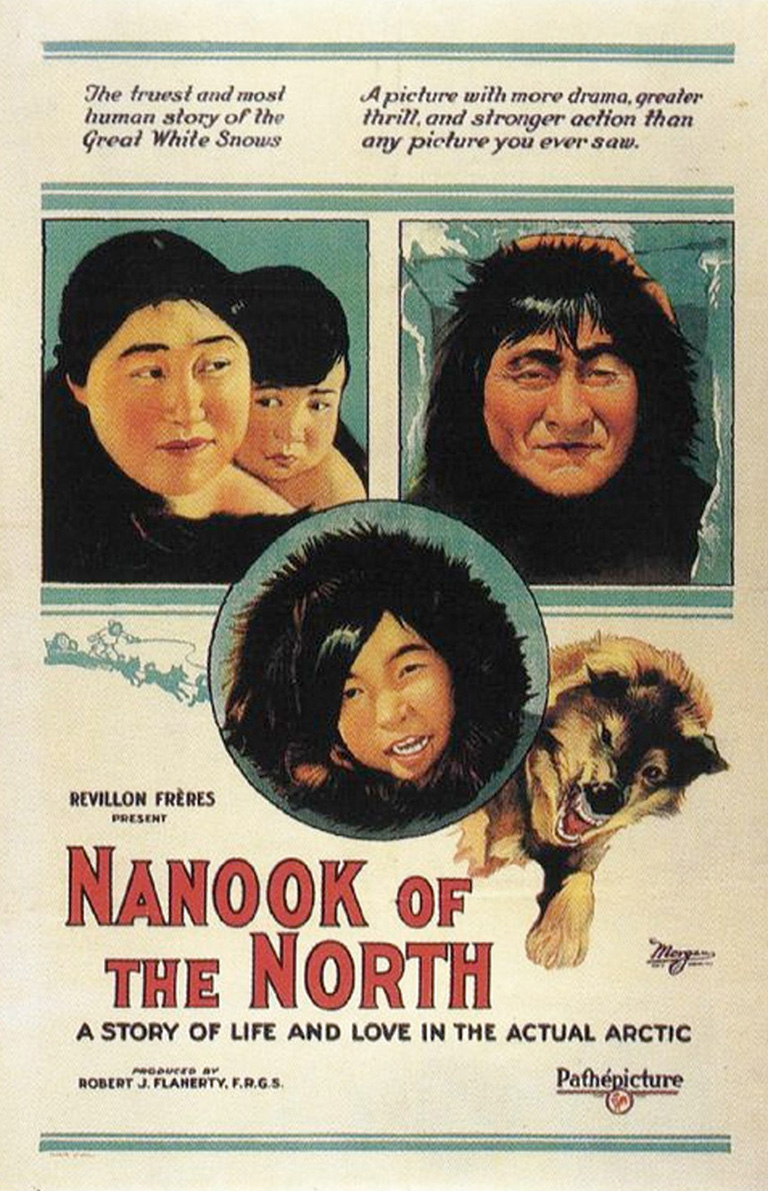

The problem was, the film was not like anything they had seen before. It was not a travelogue of the North, nor was it an adventure story from an expedition. In all, five distributors rejected his film because they feared it would not sell. Finally, a Paris-based company, Pathé, agreed to take a chance.

To find a venue for the premiere, Pathé proceeded to “salt” the executive screening at New York’s biggest theatre, the Capitol. The staged audience clapped on cue, and the manager became more and more excited — when it ended, he called it a “masterpiece.”

Nanook of the North premiered at the Capitol Theatre on June 11, 1922, and became one of the most popular films of the summer. In London, Paris, and other European capitals, the film stayed in cinemas for six months or more.

Commercial spinoffs included a soft drink called the “Nanook fizz,” “Igloo” refrigeration units and an ice cream bar with Nanook’s face on the wrapper. Within a few years, critics hailed Flaherty as the first “documentary” filmmaker, and today Nanook of the North is available on DVD, re-released by Criterion in 1999.

As for Romance of the Far Fur Country, it had a far shorter life in public memory. Visual historian Peter Geller is one of the few people alive to have watched Romance of the Far Fur Country — at least, the footage that once made up the film. There are no known complete copies.

“The film doesn’t exist as it did then,” Geller says of the footage, which is in pieces at the British Film Institute archive in London. Geller, author of Northern Exposures: Photographing and Filming the Canadian North, 1920–45, has a dream of reassembling it and placing a copy in the HBC archive where it belongs.

In Winnipeg’s trendy Exchange District, a few blocks from the now vacant Allen Theatre, a February film weekend, entitled In the Shadow of the Company, is planned at Cinematheque, the city’s arthouse theatre.

On the bottom floor of a stone and brick warehouse built when Winnipeg was the western fur trade capital, screenings of rare HBC footage, dug out of the company archive across town, will take the audience on another journey north, a route similar to what Romance of the Far Fur Country took when it premiered, ninety years ago.

Fittingly, In the Shadow of the Company is sponsored in part by The Beaver magazine. And in a twist of irony, the main ticket item is a screening of Nanook of the North.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!