Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Making it Count

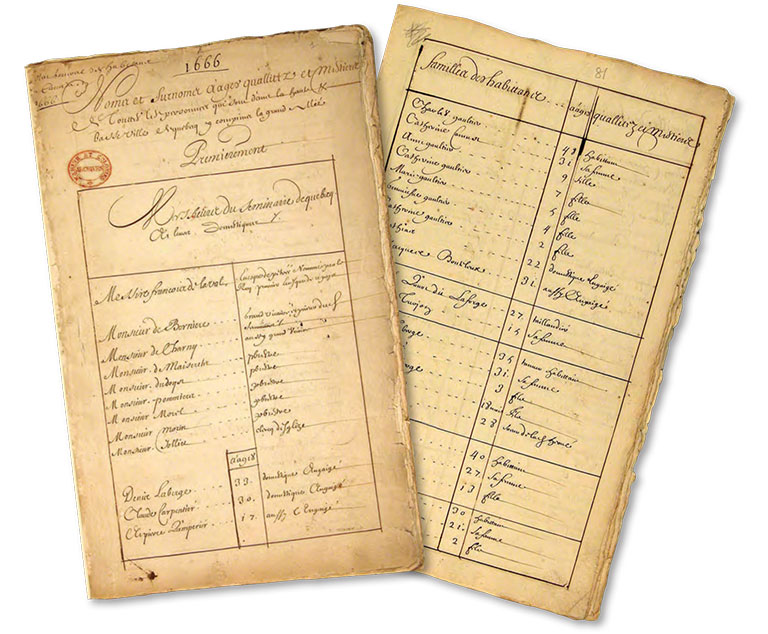

Compared to the sophisticated technology and statistical expertise behind the upcoming May 2021 census of Canada, the 1666 census of New France was a low-tech affair.

The first census undertaken in what is now Canada involved a handful of clerks working with quill pens, bottled ink, and sheaves of paper while making their way through the scattered riverside farm communities and small, raw towns of New France, mostly in the depths of winter. Their effort to make an accurate tally of a few thousand colonists took months.

Anyone with deep roots in French Quebec can enjoy finding ancestors named and identified on the “Rolle des familles” of 1666 — my own children can, but through their mother, not me. For the rest of us, the census provides an encounter with the people of a new colonial settlement: husbands and wives with broods of children and the occasional hired man on small farms cleared from the woods. Seigneurs, shoemakers, missionary priests and teaching nuns, traders, and the rest all shared a landscape that was growing into our image of New France: steep-roofed homes of stone and wood, farm lots spreading out along the long riverfront, with the forest still crowding in everywhere.

The 1666 census of New France had two authors, really. Strangely, one of them was not even born until 250 years after it was compiled.

Jean Talon orders a census

The official census taker, the one actually living in 1666, was Jean Talon. Talon came from the powerful corps of administrators called intendants, the men upon whom French King Louis XIV relied to manage his kingdom. The king had just taken back control of his colony from a private company, and Talon was his man to set it in order. Dispatched to what is now Quebec City as the first intendant of New France, Talon, not yet forty, disembarked in the colony in September 1665.

In a whirl of energy, he set about his many assignments. There was a regiment of royal troops to be supplied and provisioned as it set out to confront the colony’s great rival, the powerful Haudenosaunee Confederacy. The colony’s finances had to be set in order. A justice system had to be created. There were laws and regulations to be drafted. The fur trade had to be managed, local enterprises encouraged, and the colony’s agriculture diversified.

Talon had also been instructed, when convenient, to “visit the settlements and take an accounting of them.” He got that job started within months.

Talon had never organized a census. In 1666, almost no one had. France itself had never held a census, and Talon was given no model to follow. But in January his census takers — exactly who they were is unknown — began to tally who lived in the colony, household by household, in a census of three columns: name, age, and profession, or craft, or relationship to the head of their household.

The census took place during the coldest, snowiest winter New France had seen in thirty years. But a winter count had its advantages. Settlers were close to home, and almost no one would complicate the count by arriving in or leaving the colony mid-census.

The census takers managed to keep their ink thawed, and by summer Talon was ready to send his census to his patron at Versailles, France, the king’s powerful minister Jean Baptiste Colbert. “There are undoubtedly some omissions,” Talon acknowledged in a note at the end of the census. He promised a second, better census soon, but he proudly reported that the vital force of the colony was now established. New France had a population of 3,418 men, women, and children, he declared — a small number after fifty years of colonization, but a deeply rooted base from which to build.

Talon’s silent partner

Historians and genealogists always appreciated the details about early New France in Talon’s census, but they could not help finding more errors than Talon had been willing to admit to having included.

At Quebec City, the census included the priests and nuns and other religious personnel, but in Montreal almost all of them were left out. Most royal officials, including even Talon and the governor himself, Daniel de Rémy de Courcelle — were omitted. Among the ordinary settlers, names were missed and ages were omitted. Some people were counted twice, and more than a few families had been missed entirely. Even the final tallying of the numbers proved unreliable. Talon reported 3,418 people in total, but the actual names on the “Rolle des familles” added up to only 3,246 people. Removing duplicates and correcting some adding mistakes left the tally at 3,173.

Then, three hundred years later, Talon got a partner. What we might call the completion of the census taking of 1666 was the work of a remarkable historian in the twentieth century.

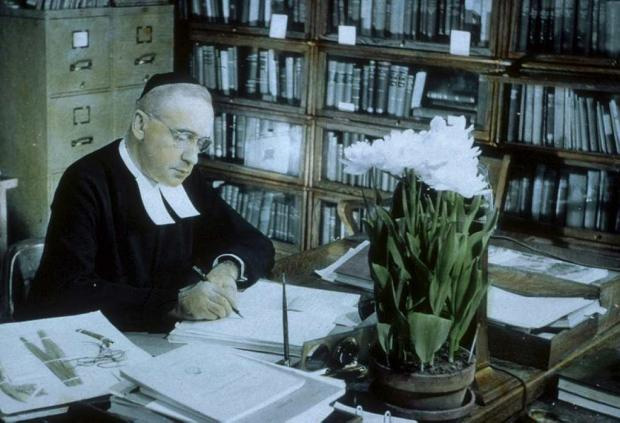

Marcel Trudel’s fellow historians called him “the man who knows everyone who lived in New France — by their first names.” Trudel was born in a village north of Trois-Rivières, Quebec, in 1917 and was orphaned at the age of five. He would come to believe his upbringing had differed only a little from that of the Trudels he found listed on Talon’s census. He, too, grew up in an isolated, rural, traditionally Catholic community. In his youth, many traditions and usages endured from the ancien régime of New France. His late-in-life memoir would emphasize how much people like him had been shaped by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

When Trudel began to study Quebec’s history in the 1940s, however, he refused to let the traditions he had inherited define the history of New France. In his youth it was mostly presented by devout clerics as the story of a saintly place, a paradise lost.

Rebelling against the clerical version of history, Trudel and others of his generation became early adherents of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution. Trudel wanted the freedom to seek “objectivity” in history, free of churchly control. History had to be “a perpetual search,” not a sermon, he declared. It had to be guided by data, not faith. Trudel’s passion for facts produced controversial results, as in the groundbreaking study of slavery in New France he produced in 1960. His candour alarmed the clerics who still controlled the universities and publishing houses where he taught and published. He eventually moved to the relative freedom he found in Ontario universities.

The Talon-Trudel census

To create a new history of New France that reflected his passion for data and for facts, Trudel really did want to know precisely who lived there at the start of the royal government. He doubted that Talon had found enough of those people in 1666 and decided that he must assemble his own record.

As someone who has done some historical research, I need to underline how crazily, terrifyingly ambitious this idea was, as well as the sheer amount of labour Trudel was undertaking to do. Imagine you once lived in a small town. Now think of starting to assemble a complete list of everyone who lived there twenty years ago. There may have been a phone book, but not everyone had a phone. Voters lists omit children and non-citizens. Property records leave out tenants. Newspapers don’t mention everyone. If there wasn’t a reliable census that year, you are in trouble. Now imagine trying the same thing for a three-hundred-year-old community where most people were illiterate and where there were no printing presses. Trudel had spent years in rectories around Quebec mining ancient, handwritten registers of baptisms, marriages, and burials, and he had spent almost as long working through the land-grant registers of the colony. From the massive index-card collections he had assembled, he believed he could fill the gaps in the census.

He could learn about how the census had been made, too. Noting here and there on the census an old man counted before he died in January, or the mention of a child not born until May, Trudel determined that the census takers had worked simultaneously all over New France and for several months. It took from January until June to count the people in Quebec City, but they had wrapped up the settlements around the city by March. The Montreal region was done by March, too, but around the Trois-Rivières region they worked from January into May.

One might guess that the census takers would have proceeded street by street and farm by farm. But Trudel knew the land-grant records as well as the parish registers. He saw that within each community there was no geographical order to Talon’s census. Perhaps the census takers simply stood outside different parish churches each Sunday and tallied the families as they gathered after Mass.

What they did observe carefully was hierarchy. This was not an egalitarian society. In each community the census takers listed royal officials, seigneurs, clergy, and any other notables first, and only then the common people.

The first name on the census is François de Laval, the bishop of Quebec; the very last is Pierre Constant, twenty-six, a recent arrival, unmarried, and claiming no craft or skill.

Because of Trudel’s labours, the first Canadian census became two censuses. The first, Talon’s, was the count taken in the winter and spring of 1666. The second, published in 1995, was Trudel’s revised edition. He had done more than correcting names, ages, and other details; he also added names the census takers had missed in every community — seventy entire families, a tenth of all the families in the colony, and dozens of individuals.

In the end, the Trudel version listed 4,219 people living in Talon’s colony in 1666. Trudel had increased the population of New France by more than twenty-five per cent.

What the census saw

What does the Talon-Trudel collaboration tell us about this early Canadian colonization venture?

It was a small place to begin. After half a century, New France’s 4,200 settlers could not match the 75,000 already settled in the English colonies in what would become the United States. The census suggests why. New France’s only industry was the fur trade, but apart from a few merchants in Montreal the census found few colonists engaged in that trade. The fur trader and future Hudson Bay Company founder Médard Chouart des Groseilliers can be found on the 1666 census, though he was then actually in England with his partner, Pierre Radisson, who is marked “absent from the country.” But mostly the fur trade of 1666 was run by the First Nations and a handful of French merchants. The trade would eventually extend New France’s reach across half of North America, but it would never employ its people in large numbers.

Already the people of New France were very separate from the Indigenous peoples of North America. At Trois-Rivières, the census notes Pierre Couc and his Algonquin wife, Marie, both in their thirties, with their four children; but such families are rare in the census. Some of New France’s founders had foreseen a merging of French and Indigenous peoples, but that mingling would mostly involve male colonists drawn inland by the fur trade, with their children growing up as Wendat, or Ottawa, or Cree in the communities of their mothers. By 1666, the settlement colony occupied the St. Lawrence Valley. The home territories of its First Nations allies and rivals were mostly elsewhere, independent of New France. Even nearby Indigenous communities were not included in the census.

The large number of families where the census identifies the household head as a habitant — generally meaning one who held a farm lot — confirms at a glance that New France was already rural and agricultural. Already in 1666, farms with newly cleared fields of wheat, and oats, and buckwheat, some pigs and cattle, and with a vast supply of firewood in the surrounding woods, lay along the riverbanks from below Quebec City up to Île de Montréal. Since few other livelihoods existed, New France was becoming a colony of farmers. With little to export and few markets, they were likely to be largely self-sufficient and cash-poor for a long time.

Farms could thrive only as family enterprises, and the census reveals that early New France was dangerously male. Men outnumber women almost two to one on the census. For every family there were long lists of young single men who were likely to return to France if they found no one to marry.

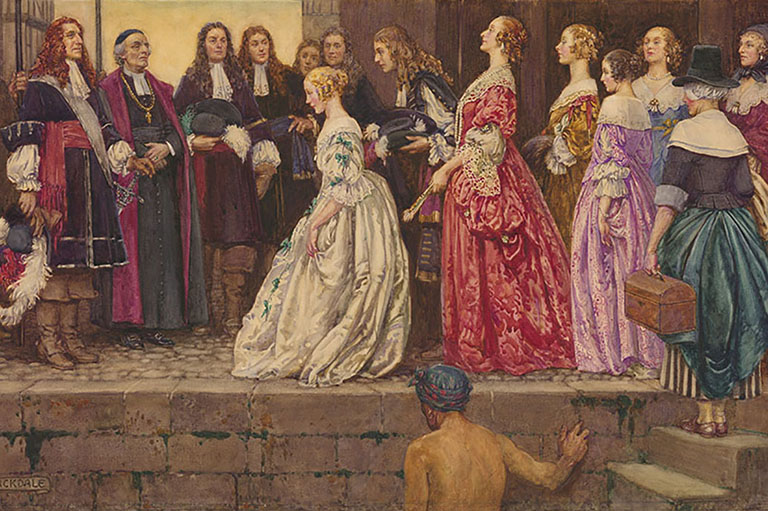

To avert that, the royal government had already begun the recruitment of the filles à marier (marriageable girls) and then the women known as the filles du roi (the King’s daughters). These were young women, often orphaned or otherwise left unsupported and vulnerable in France, who chose a subsidized passage to New France over the uncertainties of home.

Few of them failed to find husbands, and their names are found throughout the census. Twenty-two-year-old Françoise Heuché had arrived in 1664, and she married Guillaume Beaupré, twenty-three, the son of a settler, in October. She was tallied on the census with him and their infant son, Nicolas. Marie Martin, just sixteen, arrived with her brother about the same time as Jean Talon in 1665, got married in February 1666, and was tallied soon after alongside her brand-new husband, Jean Lavallée, twenty-four, habitant.

These women on the census, and over seven hundred more young women who arrived over a couple of decades, secured the future of New France. Healthier, better housed and fed, and married younger than their sisters in France tended to be, these women and their daughters raised large families. For a century and more, the colony would have a birth rate far higher than the “baby boom” of the 1950s. The many children ensured rapid growth in the colony’s population, and they would figure in the family trees of a large proportion of old-stock Quebeckers.

As in all pre-modern societies, however, as many as a quarter of all New France’s newborns died in their first year, and many mothers died in childbirth. Trudel’s version of the census, to which he added birth and death dates, is filled with the names of infants born, baptized, and buried within a few days. The census includes many young fathers who had remarried after the death in childbirth of a first wife. Men died young, too — from wars, and accidents, and illnesses — and widows with farms and infants to maintain remarried promptly. Blended families are everywhere on the census.

Talon, a busy bureaucrat with a hundred other tasks demanding his attention, had little to say about what he thought his census said about the colony. Marcel Trudel, always the man of facts, was almost as restrained. But he did mention one clue he had found in the census about what kind of people his ancestors had been.

The census takers, instead of going door to door, had expected people to come to them. The thousand people they missed, Trudel suspected, must have been the ones who decided not to turn up. Perhaps, he thought, they calculated that if the king was taking names it was probably to tax or to to control them somehow. They were too independent to fall for that, a bit rebellious, not so inclined to do as they were told. Perhaps the Marcel Trudel who broke with the received history of New France was just like his ancestors, after all.

Colbert, Louis XIV’s powerful minister who had sent Talon to New France, told him he wanted a census to tell him the “force” of the colony, by which he probably meant its ability to support and to defend itself. All censuses have that kind of practical significance. In 2021 as in 1666, sound planning depends on sound census data.

Almost anyone who has done family history has experienced the slight shock of suddenly encountering an ancestor’s name amid the cold print of official records and has sensed the personal meanings a census can have along with all that practical data. Where else but on a census text might we encounter the newborn daughter of Jean Pelletier and Anne Langlois, habitants on Île d’Orléans? She was noted by Talon’s census takers as an unnamed “daughter not yet baptised,” eight days old. Marcel Trudel’s revisions add a little more: that she was born January 29, 1666, censused about the sixth of February, baptised Marie-Delphine on February 7 — and buried on February 27.

THE HISTORY OF CENSUSES IN CANADA

- Between 1666 and 1867, almost a hundred censuses were undertaken in various parts of what is now Canada.

- The Province of Canada started the practice of taking a census every ten years in 1851. Other provinces and the federal government gradually adopted that schedule.

- Taking a census every decade is required by Canada’s constitution. A reliable and frequent count of the population is essential to ensuring accurate representation in Parliament and in the provincial legislatures.

- Since 1956, a less-detailed census of Canada has been held every ten years, five years apart from the larger census.

- Census questions have changed regularly, depending on how interested policy makers have been in religious affiliation, ethnicity, language, education, employment, income, and other matters.

- All the information in Canadian censuses up to 1921 is now open to the public. Many censuses have been elaborately digitized and made searchable by genealogical services or by volunteers.

- In 2006, Statistics Canada declared that privacy law required it to destroy the raw data about individual Canadians in the census. Only the general findings will be preserved, and future researchers will not be able to consult all the small details of the 2006 census.

- In 2011, after complaints that the government was using the census to spy on Canadians, the detailed “long form” census was declared voluntary rather than mandatory, and many Canadians declined to complete it. Data from 2011 will need the kinds of revision and correction that Marcel Trudel gave to Jean Talon’s 1666 census.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.