Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Riots on the Rock

From its early days as a British colony, through its time as an independent dominion, and up until it joined Canadian Confederation in 1949, Newfoundland has had a tumultuous political history. Perhaps no more dramatic and significant were the riots of 1861.

For much of its history, Newfoundland was a British colony, governed directly by Great Britain's appointed officials. In 1855, however, Newfoundland made great strides towards independence and was granted Dominion status and moved towards a system of responsible government. Unfortunately, its new independence exposed well-rooted divisions between the English Protestant and Irish Catholic populations, who traditionally aligned with the Conservative and Liberal parties, respectively.

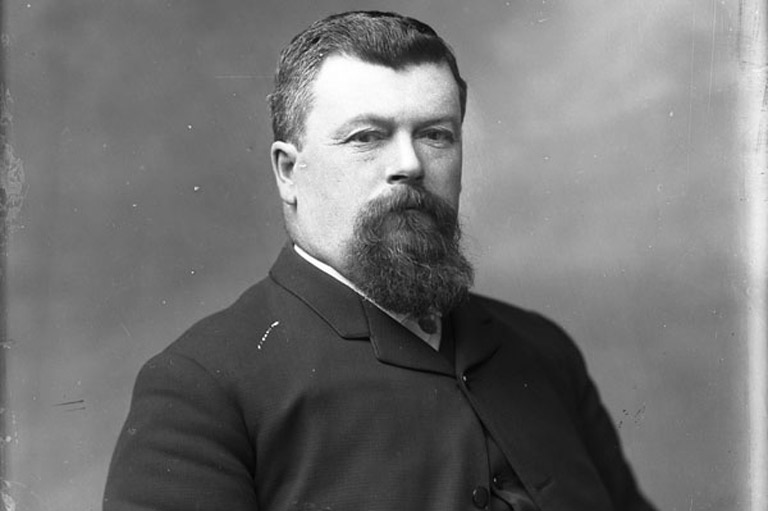

Problems in the government began to emerge in 1860 when the Liberal government’s long-time supporter Bishop Mullock became disillusioned with the party. Premier John Kent and his party were under attack for patronage, intimidation, and corruption, and the Bishop released a letter to his parishioners accusing the Liberals of being “a party who take of themselves, but do nothing for the people.” With the Bishop's considerable influence over the Roman Catholic population, these words marked the downfall of the Liberal government.

In February 1861, the Assembly introduced a currency bill that would standardize the currency for the Dominion, which previously used both the British and Newfoundland Sterling. When the opposition leader, Conservative Hugh Hoyles, criticized the bill and petitioned Governor Bannerman to oppose it, Premier Kent made a scene in the Assembly and accused both of conspiring against him and his government. Kent’s outburst was the last straw, and Governor Bannerman dismissed the Liberal government and instated Hoyles as Premier. Bannerman’s abrupt dismissal of the Liberal government quickly backfired and, because they still maintained a majority, the Liberals passed a resolution of non confidence against the Conservative government. Bannerman had no choice but to call an election.

In most ridings, the election ran much as expected, with Protestant populations electing Conservative candidates and Catholic populations supporting the Liberals. However, in a few ridings, religious divides along party lines created tense situations. In Harbour Grace, fighting broke out between supporters of the Protestant and Roman Catholic candidates. Although troops were called in to suppress the violence, they were largely ineffective. When one candidate withdrew his nomination, instead of declaring the remaining two candidates the winners of the riding’s two seats, the returning officer deferred the decision to the Assembly.

Even in Harbour Main, where four Roman Catholic candidates were running as Liberals for two seats, each were backed by different members of the Church and support was divided. Opponents went through great efforts to prevent the other side to vote and even blockaded towns to prevent residents from casting their vote. Riots broke out and the crowd even opened fired, killing one person and injuring several others. In light of the circumstances in Harbour Grace and Harbour Main, the election results were declared invalid and both ridings were effectively disenfranchised. By not filling the four seats from the two ridings, the Conservatives were given a 14 to 12 majority over the Liberals.

The Liberals felt that the disenfranchisement of the Harbour Main and Harbour Grace ridings was an attempt to prevent the party from taking power. When the Assembly opened, two of the candidates from Harbour Main took their seats in protest. Premier Hoyles demanded that they leave and police had to be brought in to remove one of the candidates.

By this point, a crowd had formed outside in support of the Liberals and they soon began to riot. Troops were called in to suppress the riot, although their presence provoked the crowd even more. A shot was fired by one of the rioters and the troops were forced to open fire on the crowd. Three people were killed, including one of the Roman Catholic priests who had been trying to restore order to the streets. Bishop Mullock rang the cathedral bells over the city, summoning the crowd to the church. There, he urged people to end the violence and to return to their homes peacefully. Fortunately, the rest of the night passed uneventfully.

The riots of 1861 represented a climax in sectarian conflict and a turning point for politics in Newfoundland. In the aftermath of the violence-ridden election, both parties, as well as their constituents, realized the danger of such divisions. Even religious leaders, like Bishop Mullock, recognized the inherent problems of having political parties aligned so closely with religion. In the years following, political parties began to move away from their religious affiliations and toward a more equal and inclusive system.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!