Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Off the Rails

Amid ripples of laughter, the parade float rolled into view.

Standing in a pink makeshift “jail cell” was a Canadian Forces private sporting a thong, women’s lingerie, and a blond wig. As the male soldier hammed it up for the crowd, signs on the float proclaimed, “2 PPCLI Express. Next Stop North Side. CT-01.” Another sign, spotted by some witnesses, read “Crazy Train.”

Written off by some military members as a harmless prank, the incident that took place at CFB Winnipeg on November 22, 2002, would spark an inquiry that revealed widespread discrimination in the military against soldiers with “operational stress disorder.” Operational stress disorder (OSI) is the contemporary name for mental illness that arises out of military operations.

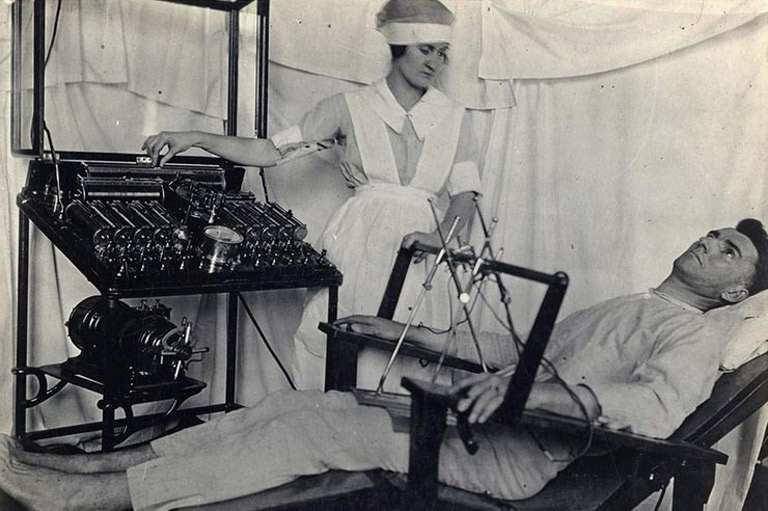

The findings of the inquiry echoed attitudes that go back all the way to the First World War, when sufferers of “shell shock” — as they called it then — were often viewed as cowards or malingerers.

The “Crazy Train” incident took place the same year Canadian troops began their deployment in Afghanistan. About four hundred men and women had gathered at Kapyong Barracks on the south side of CFB Winnipeg to celebrate a traditional day of sports competition between members of the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry.

According to a report filed in March 2003 by thenCanadian Forces Ombudsman André Morin, many witnesses found the parade to be “fun and enjoyable.” But at least one person — a civilian peer-support counsellor who works on base with OSI sufferers — wasn’t laughing. After several of his patients privately told him they had found the float offensive, he lodged a complaint with his superior officers.

The ombudsman’s investigation discovered that the term “north side” referred to the location at CFB Winnipeg where patients with OSI received treatment. The phrase “crazy train” was a derogatory term used by the rank-and-file to belittle OSI patients.

Morin titled his 2003 report “Off the Rails: Crazy Train Float Mocks Operational Stress Injury Sufferers.” It quotes one soldier involved with the float as saying: “We came up with the idea of the Crazy Train … everybody knows and talks about the Crazy Train. Some people deserve to be helped, but some individuals that have gone to the North Side don’t deserve to be there and are getting a free ride.”

The comments seemed to reflect widespread attitudes. For instance, two Forces members told investigators that they dared not report OSI symptoms to their superior officers. “If you do that, you’re blacklisted,” testified one member. “You’re expected to suck it up and soldier on,” reported another.

And in an earlier ombudsman’s report filed in February 2002, a medical officer with twenty years experience testified that soldiers diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) “are often insulted, accused of being weak, of using the system, and [are] ostracized by the unit…. Others regard these folks with disgust and very little compassion. They make fun of the soldier.”

The incidence of OSI in the military has increased in recent years due to the ongoing war in Afghanistan. In a 2008 story, The Hill Times of Ottawa stated that at least fourteen percent of Canadian troops returning from Afghanistan had reported some sort of operational stress injury. That adds up to about 3,500 of the 25,000 Canadians who have served in Afghanistan since 2002. These disorders include major or minor depression, suicidal thoughts, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or PTSD.

Changes have been made since the release of the 2003 ombudsman’s report, which had called for efforts — including educating military personnel about OSI — to erase the stigma surrounding mental health disorders in the military.

In 2009, Veterans Affairs Canada launched a new program to improve the cooordinaton of benefits and other help for veterans with operational stress injuries. Veterans Affairs offers a wide range of services to Canadian Forces members, veterans, and their families, including a number of treatment clinics across the country.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!