Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Roots: Understanding Family Photos

Such a nice family portrait, everyone in my wife’s family agreed. All her cousins have copies too. Unfortunately, none of the prints carries the name of a photographer or any annotation of date or place.

The Maynards were Protestant missionaries from the county of Kent, England, who had lived in India around the turn of the twentieth century. Around 1912, it was said, they moved to Victoria, British Columbia. The photo certainly doesn’t look like India. Possibly it was taken in Kent. Maybe B.C.

The youngest child, Joyce, was born in 1905, so the consensus from her apparent age in the photo was of a late Edwardian date. No one knew for sure and no one thought much about it. A nice shot, but families have their pictures taken all the time, right?

That was certainly my attitude, even when I used the photo to illustrate my research into the history of the Maynard family. (My late father-in-law, Max, is the worried-looking chappie at the far left.)

I had documented the missionary travels of the patriarch, Thomas Henry (Harry) Maynard, often but not always accompanied by wife Eliza (Lily) and assorted children. I had even tracked down and read the long-out-of-print autobiography of eldest son Theodore, a poet and theologian who scandalized his parents by converting to Roman Catholicism before settling in the United States.

One day it dawned on me that Theodore must have left India to attend his English boarding school long before his youngest siblings had even been born. Far from being an every-other-weekend occurrence, a Maynard family get-together was surely a rare event. Just how rare?

For each member of the family, I compiled a timeline based on family, civil, church, military, and transportation records — anything that would give information about where a family member was at a specific moment in time.

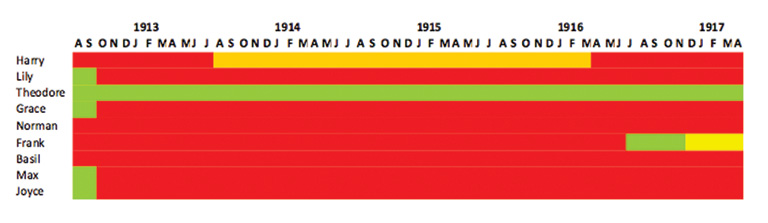

The starting point was October 1905, when Joyce was born, and the end was April 1917, when Frank died at Vimy Ridge. For each member of the family, I categorized every month by the country of residence. Rationale: To sit for a family photo, you can’t be in different countries. When were they all in the same country?

Let’s take Joyce as an example. She was born in Britain in October 1905 while her parents were on home leave from their missionary duties. According to the missionary newsletter for their sect, Joyce accompanied her mother back to India in October 1908 and stayed there until October 1911, when they all returned to Britain.

In October 1912, Joyce, her mother, and two siblings sailed from Liverpool to Montreal on the Empress of Ireland — the ship that a year and a half later would sink in the St. Lawrence River in Canada’s deadliest maritime disaster. (Joyce’s father and three of her brothers had preceded them across the Atlantic in August of that year.) Joyce then stayed in Canada with most of her family through the war years, although her father did return to India for one last hurrah between 1913 and 1916.

So here’s what the timelines look like after August 1912, when the first family members arrived in Canada. Those who have been reading attentively will be able to figure out which country is signified by each colour, but it’s not necessary to do so. The key point to note is that no column is in a single colour, and so members of the family were never all in the same country during this period and thus could not have had their photo taken together.

Similar analysis rules out the interval between June 1906 and September 1911. And prior to June 1906, two of the children were babes or infants. So, by a process of elimination, the photo must have been taken in the period between October 1911 and July 1912 when all members of the family were in Britain.

I have to admit I was quite full of myself for having narrowed down the date and location of the photo from a span of several years and three continents to one ten-month interval and a single country.

Then I was lucky enough to meet Boston-based Maureen Taylor, a.k.a. the Photo Detective. Her insights persuaded me that much more could yet be discovered. She pointed out that the healthy foliage was hardly consistent with even a mild English winter. Indeed, the trees seem to be in flower — for example, to the left of Max. If so, the photo could only have been taken in the spring.

Was there anything more to be learned from the foliage? Two experts, including one from the Royal Horticultural Society in London, concluded that the photo shows fruit trees trained on a lattice — a fashionable practice at the time — possibly cherry, apple, or pear. Foliage of this character in southern England would argue for a date in April.

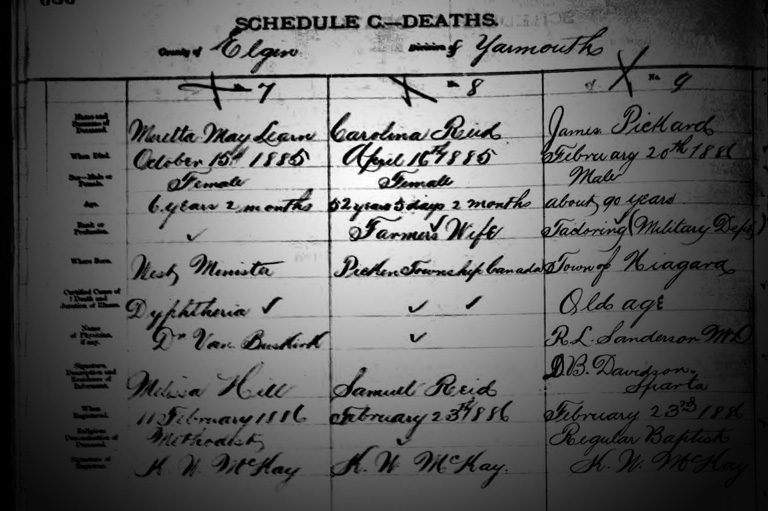

Taylor also encouraged me to consider the specific location the photo could have been taken. A very likely spot was the back garden of the Maynard home in the town of Tunbridge Wells, especially as Harry’s mother, Maria, was ill thoughout this period — indeed, she died on May 21, 1912.

It seemed a dead-cinch certainty that the Maynards must have gathered at Maria’s home during her illness, even though Theodore was living in London and Norman and Frank were attending boarding school in Margate.

But, alas, a site visit confirmed what an aerial view from Microsoft Bing had suggested: This photo could not have been taken in Maria Maynard’s postage-stamp back garden.

Then I noticed that Maria’s death certificate gave the address of Harry’s temporary lodgings in Britain: 25 Cavendish Avenue, Eastbourne. An aerial view seemed promising, and I sent a note to the local genealogical support group in what is now East Sussex.

Genealogists are helpful folk. Three people offered to pop over to Eastbourne to take a look; a fourth suggested she could nip around the corner to Cavendish Avenue; while a fifth said, no problem, he’d ask his brother who lives at number 23. The latter’s judgement after sticking his head over the fence: “I would say that the old photo was indeed taken at number 25.”

So a ten-month interval and an entire country were further winnowed to a single month and one specific back garden!

But here’s the kicker. During that ten-month period, how many family portraits did this group sit for? My guess is only one. It’s inconceivable that these pious folk, always in need of funds to spread the Lord’s word, would have paid for two photographic sessions in a matter of months.

If this conjecture is correct, we are forced to the conclusion that this was the only photograph of the Maynards taken when all members of the family were of an age to remember and appreciate the occasion. No wonder it evoked strong emotions in all those who appeared in it. No wonder it was lovingly passed down to all branches of the family, even as its significance was lost on subsequent generations!

What untold stories are waiting to be teased from your family photos?

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!