Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Roots: Coming Clean

Bring it on! That’s how contemporary family historians typically respond to discoveries of ancestral misbehaviour that shocked earlier generations.

One family recently thrilled to the unmasking of a bigamous ancestor. Meanwhile a friend enjoys sifting through the sketchy evidence that her grandfather ran booze across Lake Erie during Prohibition. For many family historians, unthinkably bad genealogical news would be a discovery that their antecedents led blandly respectable lives of no interest to anyone.

Earlier generations felt differently. The kin of those who had disgraced the family took active measures to ensure future generations remained ignorant of the facts. A cone of silence was imposed, documents were altered, and lies passed down as gospel.

As a result, the modern-day researcher may be blissfully unaware that there’s a story to be found and cannot expect elderly family members to be helpful. Very possibly they remain active conspirators in the cover-up; at the very least they may feel, like my aunt, that these things shouldn’t be discussed.

So what do you do when you discover a delicious truth that may be unpalatable to some?

Don’t do the research — either personally or through a professional — unless you’re prepared to accept extreme and unexpected consequences.

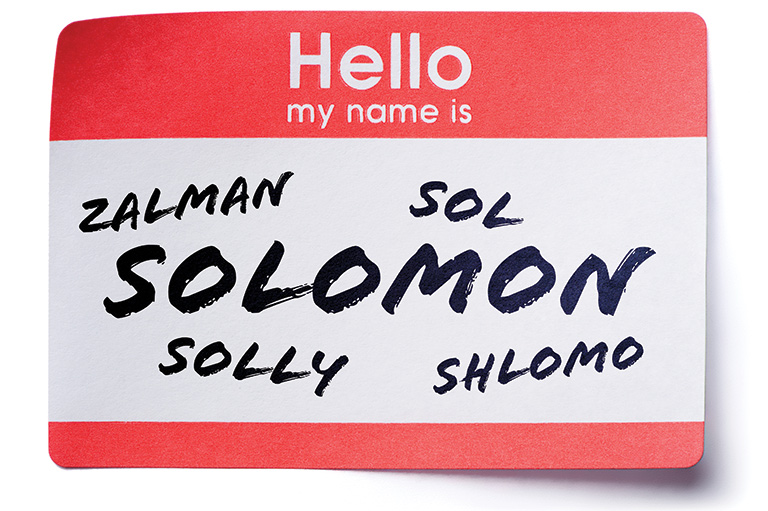

More often than not, untold tales involve sexual or connubial peccadilloes, such as a stay in the army VD clinic, an undisclosed prior marriage or bigamy, or an illegitimate child.

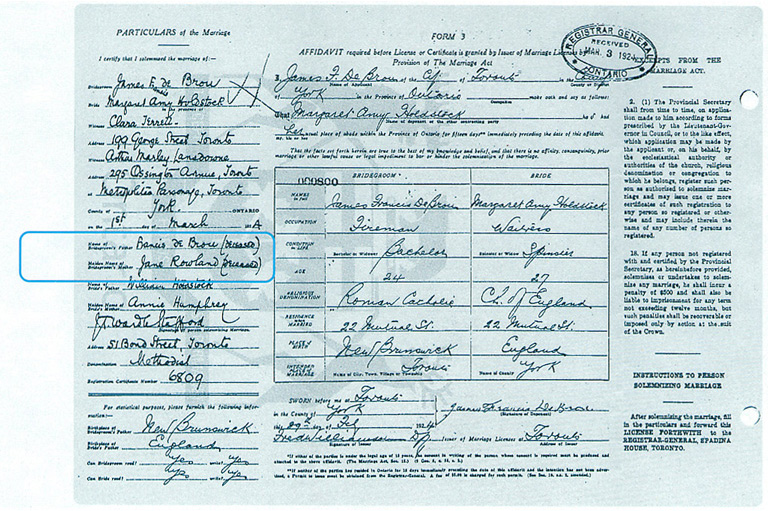

The all-time favourite fudge was the propagation of a fictitious marriage date in order to allow for a full nine-month term for the first-born child. Search hard enough and you’ll probably find examples in most family trees, including my own.

Few, though, will have experienced the same drama as a genealogical friend who inadvertently displayed a correct marriage date on a family tree distributed at a gathering of the clan. Several cousins pointed out the “error,” including one who had been born just five months after his parents’ actual wedding.

What would you say to this person? Would you come clean?

If you were a professional researcher, you would have no choice. The code of ethics of the Association of Professional Genealogists requires that members “refrain from withholding, suppressing … sources or data.”

A common-sense rule is this: Don’t do the research — either personally or through a professional — unless you’re prepared to accept extreme and unexpected consequences. This applies to genetic as well as archival research. How would you feel, for example, if you were to learn from a DNA test that your sibling is only a half-brother or half-sister?

Sometimes news may be unwelcome, even if it shouldn’t be. One expert in Canada’s black pioneer families is sometimes embraced and sometimes rebuffed when she approaches descendants who have always defined themselves as one hundred percent white.

What if research uncovers grievous moral failing or unbearable tragedy? Surely no one wants to prove descent from a rapist or someone who participated in a lynch mob. And who would not feel unspeakable pain at the discovery that a parent or grandparent had lost a young child in heartbreaking circumstances? Would you wish to inflict that pain on other family members?

One group of researchers who have confronted their shared pain includes those whose ancestors were shot at dawn for “cowardice” in the First World War — 312 in total, including twenty-five Canadians — many of them clearly suffering from what we know today as PTSD. Through the efforts of the descendants, pardons have been granted and we all better understand the unpredictable impact of prolonged stress on the psyche.

Most of us don’t belong to such support groups and would have to think twice before disseminating to all and sundry unexpected findings of mental illness, runins with the law, gross sexual impropriety, or other shortcomings in recent generations.

The consensus view is best expressed by a researcher friend: “I keep ‘unwelcome’ findings about my more contemporary ancestors (parents, grandparents, and collaterals) to myself and a select few family members out of consideration for those living relatives who would be upset if the findings were made public.”

When it comes to generations gone and forgotten, most genealogists have no qualms about full disclosure. As one elderly relative put it to a researcher, “There’s nothing new under the sun, but people talk about it more these days.”

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!