Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

The Hair of the Dog

Dog breeders have long debated which canine breed can lay claim to being the oldest. Contenders for the title include greyhounds, which are similar to dogs that appear in Egyptian hieroglyphs; passionate advocates of these slender canines also assert that Alexander the Great owned a greyhound named Peritas. Other contenders for early breeding include the hairless chihuahua and the long-haired Pekinese; the former resembles skeletal remains found in Mexico as early as 800 AD, while the latter, which was bred by Chinese royalty, goes back at least five hundred years.

Dogs themselves are much older, of course. Remains estimated to be about 14,000 years old have been found in Germany; slightly younger remains – about 13,500 years old – have been found in Israel; and canine skeletons about 10,500 years old have been found in archaeological digs in Idaho.

There seems to be no question that dogs were the first animals to be domesticated, perhaps 15,000 years ago, and while domestication may have occurred independently in a number of places, recent genetic tests prove that all dogs are descended from a Eurasian stock of wild dogs, and not from wolves, as has long been commonly believed.

These ancestral canines, which arrived in North America with their human owners, served a number of purposes: as hunters, guards, sentinels, and as draft animals, pulling travois for members of mobile societies prior to the reintroduction of horses to North America in the late fifteenth century. The care with which they were buried, at least in some circumstances, indicates that these hard-working dogs were highly valued. However, they were not selectively bred, a process that requires isolation during periods of female fertility.

The sleek Egyptian and Macedonian dogs mentioned above undoubtedly have a legitimate claim to antiquity, but a remarkable line of North American dogs, the Salishan wool dogs, may be even older and might also be the world’s most unusual breed.

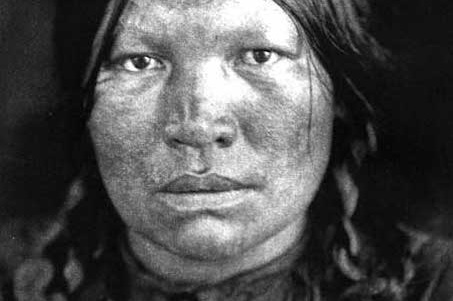

Developed by Salishan-speaking peoples of what are now southwestern British Columbia and the neighbouring state of Washington, this singular breed is now, unfortunately, extinct. Known as sko-mai or ki-mia in the many Coast Salish languages, and xlit selken among the Nlaka’pamux of the Thompson River region, who speak an Interior Salish dialect, the medium-sized wool dog was raised for its thick, soft, generally white or dun-coloured hair, like sheep or goats.

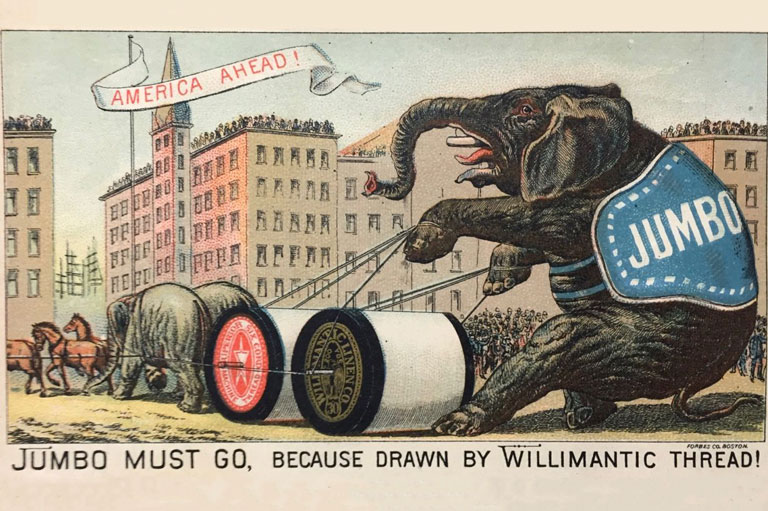

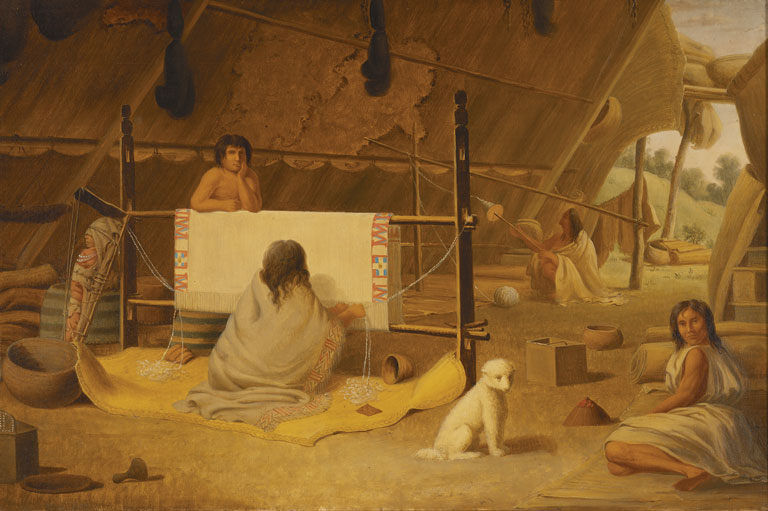

Carefully isolated when in heat, often on islands or in pens, wool dogs were regularly shorn close to the skin, like their ruminant counterparts. But their wool was not used for just any type of garment; instead, sometimes combined with the fine wool of elusive mountain goats, as well as plant fibres, it was used to create the magnificent blankets for which coastal British Columbians are celebrated today. For hundreds of years, these beautiful blankets were perhaps the ultimate symbol of wealth on the northwest coast. Given as gifts at potlatches or used to wrap the dead for burial, they displayed the donor’s generosity, wealth, and status.

Unfortunately, the blankets have rarely been found in archaeological sites, since most natural fibres rapidly decompose. As a result, it is not clear when they were first made and, by extension, when wool dogs were first successfully bred.

Simon Fraser University archaeologist David Burley has suggested that, since breeding for such specialized traits would take time and patience, and given that the resulting wool and blankets would only be of value to a complex and highly stratified culture, wool dogs may well stretch back to British Columbia’s early Marpole culture some 2,500 years ago (almost 200 years before Alexander the Great’s lifetime) or even to the Locarno Beach culture that preceded it 1,000 years before (some 400 years before Egyptian hieroglyphic writing was developed).

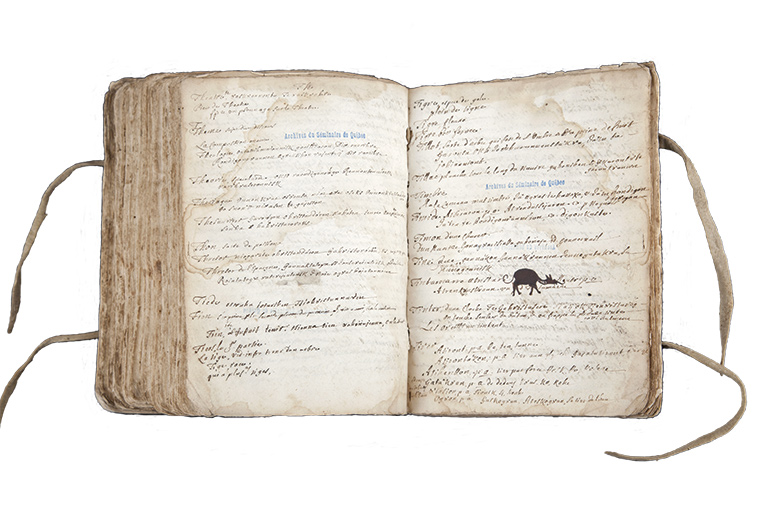

Several pieces of evidence combine to suggest that wool dogs were a valued part of life for people from Vancouver Island to the Fraser Canyon and south to the Olympic Peninsula by 1500 BP (“Before Present,” using 1950 as a baseline date). Grant Keddie, archaeological curator of the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, believes that two dogs buried in middens dating from that period on southern Vancouver Island may be wool dogs. In part, this is because he has also discovered blanket pins, spindle whorls, and antler combs in midden layers dating to the same period (the last of these possibly used for tamping the weft or woven fibres tightly to create a sturdy woven cloth).

Retired dean of British Columbia archaeology, Roy Carlson of Simon Fraser University, and others have frequently unearthed decorated and highly polished bone and antler blanket pins, as well as spindle whorls of whalebone or a soft, easily carved soapstone called steatite, in late Marpole sites on the Lower Mainland. Virtually all are 1,500 years old or younger. Older spindle whorls are rarely found, likely because most were made of wood.

Wool dogs clearly continued to be bred and their wool used ceremonially for more than a millennium, for many of the first European adventurers and traders, including George Vancouver, Simon Fraser, and Alexander Mackenzie, made a point of commenting on both the animals and the remarkable items made from their hair. Of his visit to a village near present-day Yale in 1808, Fraser wrote, “They have rugs made from the wool of Aspai or wild goat, and from Dog’s hair ... we also observed that the dogs were recently shorn.” Villages in the area were apparently famous for their exquisite blankets or “rugs.”

Wool dogs were not the only canines found in the West Coast villages, though. There, and in other aboriginal villages across North America, were dozens of the ubiquitous “camp dogs,” or “little buffalo dogs” as they were often called on the Prairies. About the size of a coyote, with large, erect ears and long, brushlike tails, camp dogs were once crucial to the well-being of native North Americans. They were trained to protect villages, guard and entertain children, herd buffalo, and even swim under water to drive fish into nets.

Largely because of their resemblance to coyotes, camp dogs were hunted almost to extinction, according to breeder Kim La Flamme. Kept as pet or guard dogs, they are prized for their intelligence, versatility, and devoted nature, as well as for their remarkable vocalizations. As a result of their unusual high-pitched barks and howls, these animals are also known as “song dogs.” Individuals, which vary in colour from black to fawn and cream, and have amber, gray, or even blue eyes, are agile and remarkably willing to please. Members of this ancient breed can be taught to climb trees and will instinctively stay one step ahead of their owners. Today, fewer than three hundred exist worldwide, according to La Flamme.

For wool dogs, however, the arrival of Europeans was a death knell. Traders flooded the market with cheap blankets and, later, sheep’s wool. Without careful breeding, the dogs quickly disappeared. By 1858, wrote anthropologist F.W. Howay, “the blankets themselves were very scarce, and the wonderful dog had become almost extinct.” In the Canadian Journal of Archaeology in 1994, author Rick Schulting wrote, “The last account of what was possibly a living pure-bred wool dog comes from 1862, when the first postmaster of Vancouver seems to have seen a dog fitting that description at a Lower Fraser band potlatch.”

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!