Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Rupert's Land

Sometimes the course of history hinges on small things, such as the baby who was almost left behind when members of his household escaped their embattled castle in Prague in November of 1620.

Eleven-month-old Prince Rupert of the Rhine was crying on the floor of a drawing room in the empty Hradcany Castle, forgotten or abandoned by his nurse as the household fled the approaching army. A final search of the palace by the royal chamberlain saved baby Rupert, who was tossed into the last carriage to leave the castle.

Thanks to the servant’s quick action, Rupert survived to grow up in exile, land at the court of his English royal relatives as an adult, and use his influence to establish the Hudson’s Bay Company, thereby shaping Canada’s destiny.

Rupert certainly left his mark on the map of Canada. For two hundred years, from 1670 to 1870, the Hudson Bay drainage basin was known as Rupert’s Land, honouring the prince’s founding role as first governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

This vast territory ultimately became the provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan as well as southern Alberta, southern Nunavut, northern Ontario, and northern Quebec. It also included parts of what are now Montana, Minnesota, and North and South Dakota.

Today, Prince Rupert’s name remains a part of Canadian geography. He is the namesake of the city of Prince Rupert, British Columbia, the Prince Rupert neighbourhood in northwest Edmonton, and Quebec’s Rupert River, which drains into Rupert Bay on James Bay. Despite all this, the man behind the name on the map is virtually unknown to Canadians.

The history section of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s website acknowledges that “it took the vision and connections of Prince Rupert, cousin of King Charles II, to acquire the Royal Charter which, in May, 1670 granted the lands of the Hudson Bay watershed to ‘the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay.’”

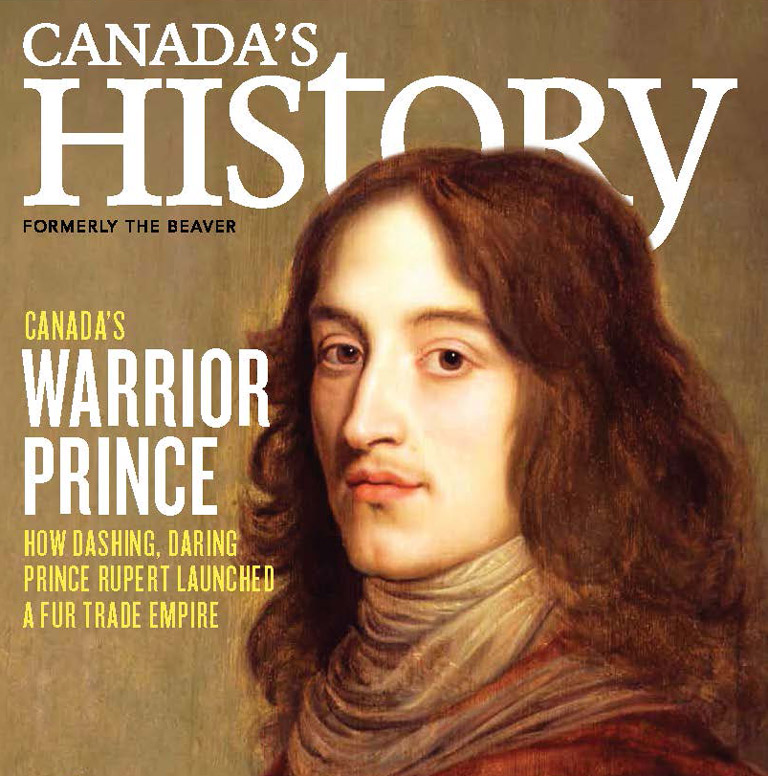

But who was Prince Rupert? Like King Louis XIV of France, who transformed New France into a royal province, or Queen Vicroria of Great Britain, whose birthday is a national holiday in Canada to celebrate her role as a “Mother of Confederation,” Rupert is one of those royal personages who had a profound influence on Canada without ever setting foot on Canadian soil. The first HBC governor, however, was not a typical royal.

In contrast to Louis XIV or Victoria, who spent most of their lives in their homelands and came into secure royal inheritances, Rupert was a wanderer, a younger son of an exiled king. The political turmoil of seventeenth-century Europe obliged Rupert to find his own way in the world. Rupert applied his formidable energy and intellect to a wide variety of professions. Over the course of his lifetime, he would become a soldier, an artist, a general, a privateer, and a scientist. But most of all he would be an explorer and traveller, eager to find new possibilities in new lands.

The circumstances of Rupert’s flight from Prague as an infant during the Thirty Years War (1618-48) shaped the course of his entire life. His father was Prince Frederick of the Rhine. Frederick was a Calvinist, so, when Protestant Bohemians in Prague rebelled against the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II, he took their side, becoming king of Bohemia (the modern-day Czech Republic) in 1619.

His reign lasted just over one year. Seeking to make an example of the prince who had dared to usurp the Bohemian throne, Emperor Ferdinand confiscated Frederick’s castle in Heidelberg and his lands along the Rhine. The now homeless Frederick—nicknamed the Winter King for his short reign—found refuge with his family in the Netherlands.

At the Prisenhof palace in Leiden, his thirteen children, including young Rupert, played games of make-believe, arranging chairs into an imaginary carriage and pretending they were going home to Heidelberg.

As he grew into a young man, Rupert realized that his family would not be going home to a comfortable royal inheritance anytime soon. His father died in 1632. The only chance his family had to regain their German lands was to obtain the support of his mother’s powerful relatives in Britain. Rupert’s mother, Princess Elizabeth, was the older sister of King Charles I of England, Scotland, and Ireland. In 1635, she sent the high-spirited Rupert and his more subdued elder brother Charles Louis to England to be received at the king’s court.

Rupert’s mother realized that sending her brilliant but impetuous third son to England was a bit of a risk. She wrote to Sir Henry Vane at the English court, asking him, “give your good counsel to Rupert, for he is still a little giddy, though not so much as he has been. I pray tell him when he doth ill, for he is good-natured enough, bur doth not always think of what he should do.”

The tall, dark-haired sixteen-year-old Rupert was a handsome young man and made a big impression at the English court, in part because of his straightforward manners. While experienced courtiers were careful to speak without giving offence, Rupert expressed his opinions without reserve, a trait that impressed his uncle the king and that would later enable Rupert to successfully argue the merits of establishing an English fur-trading empire on the remote shores of Hudson Bay.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

As early as 1637, Rupert’s interest in exploration was clear. The restless young prince was very keen to carry out an English proposal to establish a colony on the island of Madagascar off the southeast coast of Africa and to have himself act as governor. His mother, however, thought it was a silly idea. “As for Rupert’s romance of Madagascar, it sounds like one of Don Quixote’s conquests where he promised his trusty squire to make him king of an island,” Elizabeth wrote. With the Thirty Years War raging on the continent, she urged her son to return to Holland and to serve as a soldier under the Prince of Orange. He dutifully did so but was captured and imprisoned in a castle in Austria for three years. During that time he was allowed to hunt and to pursue other pastimes, including a romance with the daughter of the local governor.

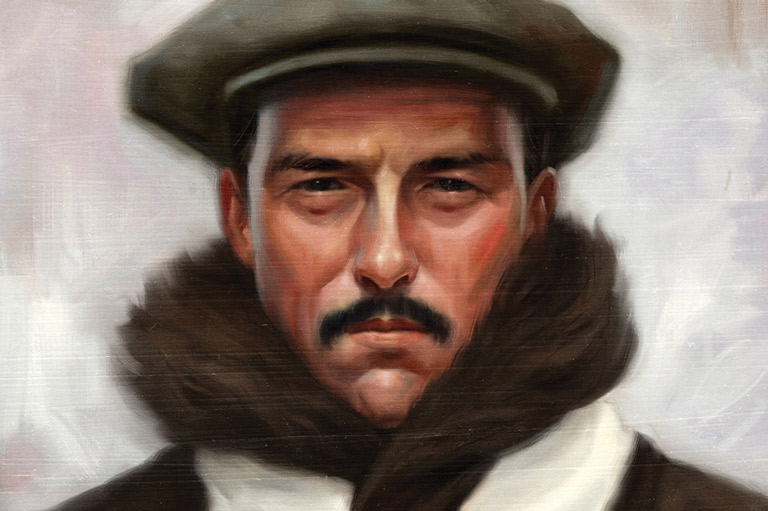

His uncle’s diplomacy eventually got him out of prison, and by 1642 twenty-three-year-old Rupert was in England serving as Charles I’s right hand military man during the English Civil War. As a royalist military advisor, task force commander, and director of cavalry, he won some early victories and gained a reputation as a daring fighter. Rupert became the quintessential royalist Cavalier: bold and fearless with a graceful bearing and long hair, always impeccably dressed in scarlet coats and wide lace collars.

His youthful brashness also made him controversial. His loyalty was to his uncle alone, and he had little interest in the complexities of English politics. “The prince was rough and passionate and loved not debate,” according to his contemporary Edward Hyde, the Earl of Clarendon, in his history of the English Civil War.

In a letter to the Earl of Essex, who led the parliamentary forces opposing the king, Rupert was characteristically straightforward: “I know my cause to be so just that I need not fear. For what I do is agreeable both to the laws of God and man, in defence of true religion, a King’s prerogative, an uncle’s right, a kingdom’s safety. Now, I have said all, and what more you expect of me be said shall be delivered in a larger field than a small sheet of paper and that by my sword and not my pen.”

The king’s other military leaders objected to Rupert’s critical appraisals of their tactics, while his opponents accused him of brutality, stating in their propaganda that he introduced the word “plunder” into the English language.

One notorious incident attributed to Rupert took place after his Cavalier forces captured Birmingham in April 1643. A parliamentary account stated that Rupert and his men “outraged the women, broke windows, spoiled the goods they could not take away, leaving little to some but bare walls, some nothing but clothes on their backs,” before setting fire to the town. Rupert dismissed these accounts as “hackney, rambling pamphlets” and insisted that he had spared the city and that the fire occurred contrary to his command after he had left the area.

By 1645, however, the royalist forces were being soundly defeated, and Rupert advised Charles I to seek a treaty with Parliament. Instead, the king regarded Rupert as having failed the royalist cause and banished him from England. Rupert landed on his feet in France, where he fought with the French army in its war against Spain. His life as a soldier ended with the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years War. The same treaty also erased his chance at obtaining a royal inheritance. The treaty gave Rupert’s elder brother Charles Louis part of their late father’s lands in southern Germany, but there was no settlement provided for the younger siblings.

At the age of twenty-nine, with no inheritance coming to him, Rupert patched up his relationship with his English relatives and embarked on a new life as a privateer. His previous loyalty to Charles I—who was executed by parliamentary forces in 1649—was transferred to the king’s exiled son, Charles II. Charles II gave Rupert command of some warships that remained in royalist hands, as well as letters of marque allowing him to seize vessels trading with England, which had became a protectorate under Oliver Cromwell in 1653. Thus Rupert would embark on an unprecedented voyage for a European prince, exploring the west coast of Africa, crossing the Atlantic, and seeing the possibilities of the New World for himself.

Rupert lost no time getting to work. Accompanied by his younger brother Maurice, he escaped from a naval blockade in Ireland and set sail for Portugal, seizing four merchant vessels during the voyage. In one letter, Rupert boasted of taking a ship from Newfoundland, saying, “we took all her fish and fried the half.” In Lisbon, Rupert and Maurice received a warm reception from King Joao IV of Portugal, a firm supporter of the royalist cause who hoped to marry his daughter, Catherine of Braganza, to Charles II (they did in fact marry in 1662). From Portugal, the fleet continued to the west coast of Africa, where the privateer princes seized Spanish ships along the Gambia River.

The fleet’s next destination was the English colony of Barbados, whose colonists had remained loyal to the Crown. Rupert had hoped to find a safe haven there, but an English Commonwealth fleet arrived before him and compelled Barbados to surrender. Even worse, hurricanes sank two of Rupert’s four ships. He lost booty as well as his younger brother Maurice. The grief-stricken Rupert recorded in his journal that his brother “lived beloved and died bewailed.” Rupert and his remaining ships and men returned to Europe in 1653 with little to contribute to the royalist cause.

The journey, however, had a profound effect on Rupert’s world view. He had seen more of the world than any of the surviving members of Europe’s royal houses and saw first-hand the possibilities of long-distance trade. His journals from the voyage carefully catalogued the resources on each of the Caribbean islands he had visited with his fleet.

After the restoration ofthe English monarchy in 1660, Rupert was better positioned than the rest of the royal family to consider the extraordinary findings of two French explorers: Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart Des Groseilliers.

The Restoration brought the forty-one-year-old Rupert more stability than he had enjoyed at any other time in his life. The new king, Charles II, made his cousin the governor of Windsor Castle, giving him a permanent home. Rupert never had the income sufficient for marriage to a princess, but there was nothing to stop him from taking mistresses. His long-rime companion was the actress Margaret “Peg” Hughes. Hughes—a plump, dark-eyed beauty—was one of the first actresses to play the role of Desdemona in William Shakespeare’s Othello, and she caught Rupert’s eye performing onstage at the King’s Theatre. Their daughter, Ruperta, was born in 1673. Rupert delighted in his new family, purchasing a stately home for his mistress and child.

The prince, middle-aged by the standards of his time, served the king as an admiral in the Royal Navy during the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 1660s, but the Restoration gave him more time to pursue his many interests. In 1662 he became a founding member of the Royal Society. He experimented with improvements to gunpowder, shot, and guns. The prince’s finances, however, remained straitened by royal standards, and he was eager for opportunities to increase his income. The possibilities demonstrated by the voyages of Radisson and Des Groseilliers combined Rupert’s need for money with his interest in exploration.

The two French explorers had undertaken expeditions into regions of modern-day Canada that were virtually unknown to Europeans. In 1658-59, they travelled beyond Lake Superior and discovered that beaver furs were plentiful in the region north and west of Superior. At that time in Europe, beaver had become scarce. But the popularity of felt hats made from beaver fur was greater than ever. Fashionable, durable, and waterproof, the hats became status symbols in Restoration England. Radisson and Des Groseilliers saw the potential to transform the fur trade from a subsistence activity to a source of untold riches by bringing the beaver felt of the Hudson Bay watershed to the eager European market. Moreover, they saw the possibility of a direct trade route between Hudson Bay and Europe. All they needed was someone to finance an exploratory trip to Hudson Bay.

To their surprise, Radisson and Des Groseilliers found that there was little interest in their discovery among the ruling elite of New France. The governor at the time, the Marquis d’Argenson, feared that establishing trading poses on the shores of Hudson Bay would divert the fur trade away from the French settlements along the St. Lawrence River. Instead of supporting further voyages inland, d’Argenson confiscated the bales of furs Radisson and Des Groseilliers had brought with them and briefly jailed Des Groseilliers for unlicensed trading.

Having been censured in New France, Radisson and Des Groseilliers travelled to New England, where they were well received. Eventually they met Colonel George Cartwright, who was there to collect taxes on behalf of Charles II. Seeing a business opportunity, Cartwright persuaded the two to return with him to England and to present their scheme before the court of Charles II.

Radisson and Des Groseilliers arrived in England in the autumn of 1665 and had an audience with Charles II. The king—who was fond of wearing beaver felt hats—was impressed by the explorers’ tales of vast beaver populations in the Hudson Bay region. Nevertheless, he was initially reluctant to involve England in the North American fur trade because that would put him into conflict with his first cousin—French King Louis XIV. The Sun King, as he was called, was an important ally and provided Charles with a pension chat allowed him to remain financially independent of the English Parliament. As interested as Charles was in developing a lucrative new source of wealth, he feared that an English presence west of New France would jeopardize his close relationship with his powerful ruling cousin.

While thinking over what to do, Charles made sure his French guests had a pleasant stay. He provided them with a small pension and housed them with cousin Rupert at Windsor Cascle. No doubt Rupert heard many tales of adventure as Radisson and Des Groseilliers stayed under his roof. He became unreservedly enthusiastic about English investment in acquiring beaver pelts from the Hudson Bay watershed. Like Radisson and Des Groseilliers, Rupert had travelled the world and saw the potential for great wealth from lands across the seas. While Charles equivocated, Rupert set to work organizing a group of private investors to finance a journey to Hudson Bay.

The prince’s royal rank and his vast array of social and military connections were crucial to realizing his vision. Rupert financed the exploratory voyage from funds advanced by King Charles’ personal banker, the Admiralty paymaster, and the customs commissioner, and he persuaded numerous wealthy investors to subscribe to the scheme. When two ships left London on June 3, 1668, Rupert and his fellow investors were rowed up the Thames to bid farewell to Radisson and Des Groseilliers, who sailed with English captains and crew back to the lands they had explored in previous years.

The return of the expedition in August of 1669 proved that it was possible—and potentially profitable—for English ships to sail across the Atlantic Ocean to Hudson Bay, spend the winter, trade with indigenous people, and return with a cargo of lucrative beaver pelts the next year. While Rupert and his fellow investors made little return on the exploratory voyage because of the initial expense of financing the expedition, the rich cargo of furs finally persuaded Charles II to risk the displeasure of the king of France.

He granted the Company of Adventurers a monopoly over trade in all the lands in the Hudson Bay watershed. After decades of service to his English royal relatives, Rupert finally had his reward.

Rupert’s name was all over the royal charter that incorporated the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1670, recognizing his pivotal role in the enterprise. The charter stated, “Wee doe assigne nominate and constitute and make our said Cousin Prince Rupert to bee the first and present Governor of the said Company.” After a vast description of the lands and privileges granted to the new company, the charter declared: “And that the said Land bee henceforth reckoned and reputed as one of our Plantacions and Colonyes in America called Ruperts Land.” Rupert and his nine fellow investors had received one of the largest royal bequests in history, sole trading rights in land that comprises nearly forty per cent of modern-day Canada.

Rupert served as governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company for twelve years. During that time, he set the tone for the company’s next few centuries of activities in what is now Canada.

Through Rupert’s influence, the company received extensive autonomy over Rupert’s Land, allowing it to build forts and to employ military personnel to defend the vast territory. Company officials also had sole authority to administrate law and dispense justice in the region.

Since the company’s focus was business, not colonization, Rupert’s negotiations with the king focused exclusively on financial matters—such as exempting trade goods bound for Rupert’s Land from customary duties. The Hudson’s Bay Company retained its monopoly in the Hudson Bay watershed until the purchase of Rupert’s Land by the Dominion of Canada in 1870.

Rupert governed the company until his death from pleurisy on November 29, 1682, at the age of sixty-three. In his will, the prince left a sizeable inheritance to his mistress and his daughter. Ruperta would go on to marry a Member of Parliament, Lieutenant-General Emanuel Scrope Howe, in 1695 and bore three sons and two daughters. Through his five grandchildren, Rupert has descendants alive today in the United Kingdom.

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, first governor ofthe Hudson’s Bay Company, had a profound effect on Canada’s history. Following his flight from Prague as an infant, he spent his life constantly on the move, undertaking military service in continental Europe and Great Britain and leading the royalist navy to the west coast ofAfrica and the Caribbean. Rupert’s travels enabled him to recognize the significance of Radisson’s and Des Groseilliers’ discoveries and to envision an enterprise with the vast scope of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Moreover, the grant of Rupert’s Land to the company discouraged the Americans from expanding northward after the Thirteen Colonies declared their independence in the late eighteenth century.

Prince Rupert not only left his mark on the map of Canada, he helped to forge the modern nation.

Man of War

Prince Rupert lived in an age of constant conflict.

Thirty Years War (1618–48)

This series of wars in central Europe started as a religious conflict between Catholics and Protestants within the fragmenting Holy Roman Empire. It later expanded into a political conflict involving the Kingdom of France and the Hapsburg dynasty.

Prince Rupert’s exile as an infant from Prague to the Netherlands came as a consequence of the Thirty Years War. His family also lost its land and castle because of the war.

Eighty Years War (1568–1648)

The Dutch war of independence was fought mainly between the provinces of the Low Countries and their Spanish overlords. After a twelve-year truce, the conflict resumed in 1619 with the start of the Thirty Years War.

The exiled Prince Rupert fought with Dutch forces under Frederick Henry, the Prince of Orange, from the age of fourteen to eighteen (1633&#ndash;37). At age nineteen, Rupert left the Netherlands to join a failed campaign to regain his family’s lands in Germany—part of the Thirty Years War.

English Civil War (1642–51)

The civil war was actually three distinct conflicts that pitted parliamentarians against royalists and involved the kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Religious differences between the three kingdoms—all ruled by one king—as well as disagreements over the power held by Parliament and the monarchy led to the outbreak of war.

Since Rupert had plenty of military experience, and since King Charles I was his uncle, he joined the royalist cause in 1642 and became its foremost military commander.

Anglo-Dutch Wars (1652–1784)

The Dutch and English were frequently at loggerheads over trade, colonial control, and naval supremacy. Both had large mercantile fleets and powerful navies; thus their battles took place at sea.

Although Rupert and his family had been sheltered by the Dutch, and he had fought for them in his youth, his first loyalty was to the English.

In spite of failing health from old war wounds and recurring malaria, Rupert served with distinction as a senior naval commander during the second and third of the four Anglo-Dutch Wars.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!