Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Lava Land

-

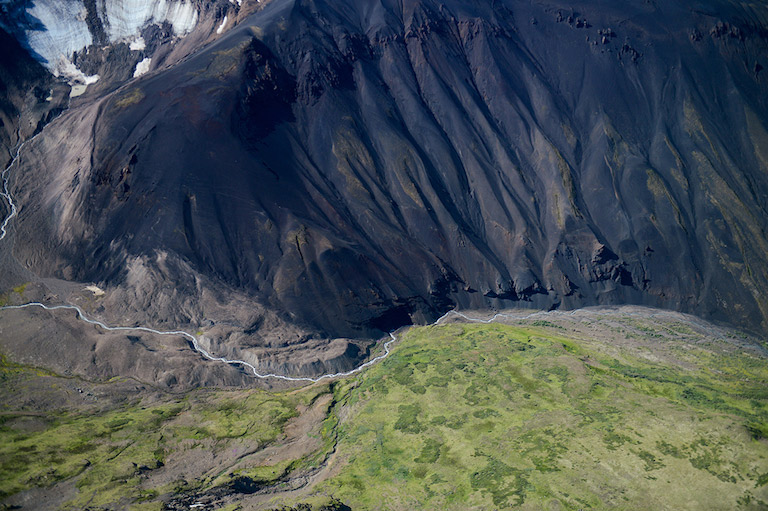

A view of B.C.'s Spectrum RangeFrancois-Xavier De Ruydts

A view of B.C.'s Spectrum RangeFrancois-Xavier De Ruydts -

A view of B.C's Spectrum Range.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts

A view of B.C's Spectrum Range.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts -

A view of B.C.'s Spectrum Range.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts

A view of B.C.'s Spectrum Range.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts -

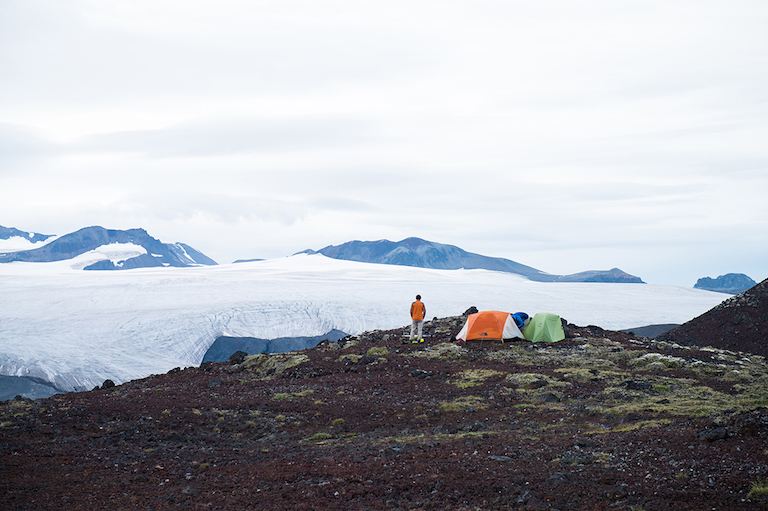

Tenting while overlooking the snow covered Spectrum Range.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts

Tenting while overlooking the snow covered Spectrum Range.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts -

A hiker walks the Armadillo Peak in British Columbia's Spectrum Range.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts

A hiker walks the Armadillo Peak in British Columbia's Spectrum Range.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts -

Sun over mountains.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts

Sun over mountains.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts -

Sunbeams across mountains.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts

Sunbeams across mountains.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts -

Pink snow.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts

Pink snow.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts -

A river flows.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts

A river flows.Francois-Xavier De Ruydts

The mountains of Canada’s West Coast are spectacular, but what often gets missed are the volcanoes that come with those mountains. British Columbia, Yukon, and Alaska are situated on the Pacific Ring of Fire. The sulfurous hot springs found all over the region are more than just places to enjoy a soak; they are reminders of the vigorous activity taking place just below the surface, where shifting tectonic plates threaten to trigger earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

Earthquakes are not uncommon — the last big one, at 7.7 magnitude, rolled through the Haida Gwaii region of B.C. in 2012. No casualties or structural damage resulted from this quake, but it did cause some hot springs to temporarily dry up. Volcanic eruptions are much less frequent.

Canada’s last major eruption took place about 2,360 years ago at Mount Meager, a volcano northwest of Pemberton, B.C. As recently as October 2016, geologists were investigating the presence of new gas vents (fumaroles) atop this mountain. They discovered steam, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulphide escaping from the vents — but no sulphur dioxide, which could indicate the presence of magma and a potential volcanic eruption.

British Columbia has no less than ten volcanic fields and belts, each with a unique origin.

Among the most majestic of these are the volcanoes of the Mount Edziza volcanic complex in the northwestern part of the province. Located within what is known as the northern Cordilleran volcanic province, the complex includes the Spectrum Range, about fifty kilometres north of Mount Edziza. Named for its beautiful rock that covers every colour of the rainbow, the Spectrum Range contains one of the most stunning geological displays in Canada.

Mount Edziza, located within a remote provincial park that is without vehicle access, has been dormant for ten thousand years, but numerous small eruptions have taken place around it, creating more than thirty black cinder cones on the wild plains extending from the mountain’s base. Formed about thirteen hundred years ago, the bare cones are perfectly symmetrical and unaltered by erosion, a sharp contrast to the vegetation around them.

Mount Edziza itself is a rugged mountain covered with a thick ice cap from which glaciers flow in all directions like lava.

Another area of interest to volcanologists in B.C. is the Juan de Fuca plate, which extends from southern Oregon to the north of Vancouver Island and is slowly subducting under the adjacent North American plate. As it plunges downward and pressure increases, the plate transforms, releasing liquids that melt adjacent rock. This magma then rises to the surface and has, over millions of years, created a chain of volcanoes called the Cascade volcanic arc.

In present-day Washington state, the active volcanoes of Mount Ranier, Mount Baker, and Mount St. Helens are all part of this volcanic arc. Mount St. Helens is notorious for a catastrophic eruption in 1980 that killed fifty-seven people and laid waste to a large area surrounding the mountain.

Volcanoes have shaped the landscape in which we live for the past two hundred million years and will continue to do so long after we have disappeared from the surface of the earth. One thing is for sure: They will keep erupting regardless of who is in the way and will always be reminders of how small we are.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!