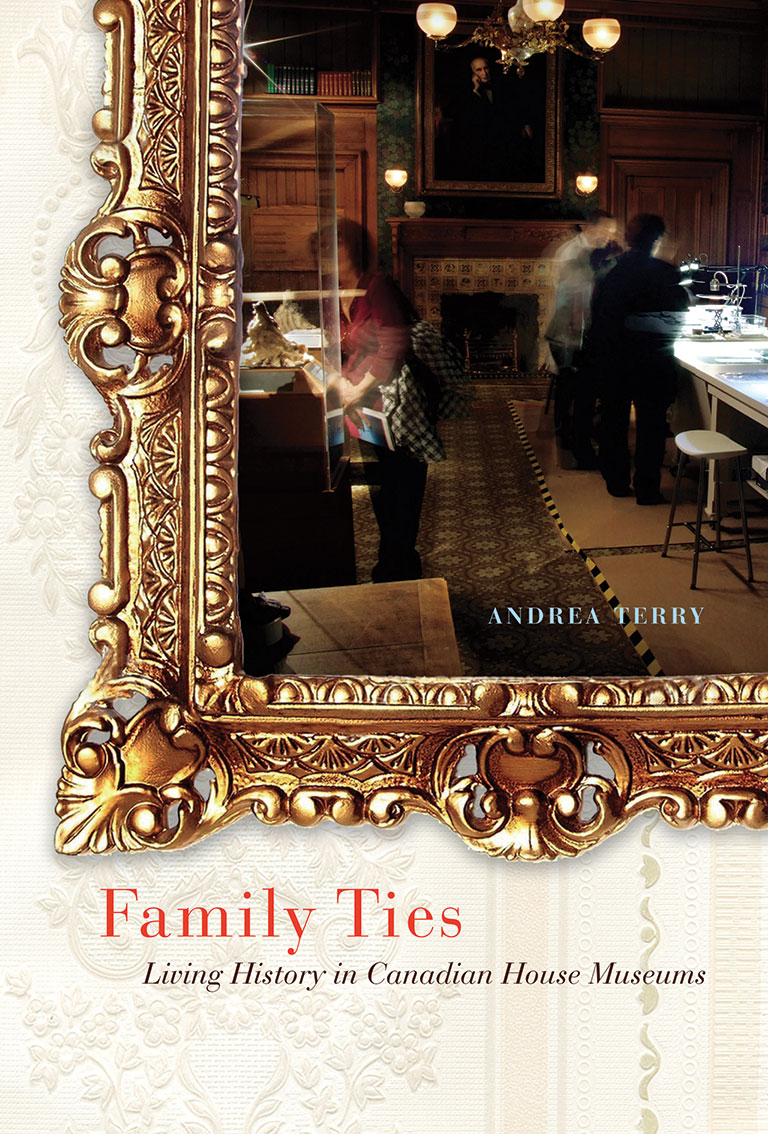

Family Ties

Family Ties: Living History in Canadian House Museums

by Andrea Terry

McGill-Queen’s University Press

264 pages, $44.95

A double review with

Time Travel: Tourism and the Rise of the Living History Museum in Mid-Twentieth-Century Canada

by Alan Gordon

UBC Press,

372 pages, $34.95

Museums are in a state of constant change. They have moved from the Victorian cabinets of curiosities to more sophisticated sites that offer storylines, reconstructions,and films. In recent years, Canadians have been able to access virtual museums and museums of ideas — those with few artifacts and based around organizational concepts. Nonetheless, there is a desire in almost all history museums to retain a sense of authenticity. This is not Disneyland. The truth matters in museums. And yet the truth, of course, is always contested.

Alan Gordon’s fine book Time Travel explores the rise of living history museums in Canada from the mid-twentieth century. Through animators and reconstructed historical sites, these new museums hoped to bring life to dead history.

Gordon’s deeply researched book will become a classic in the field of cultural policy and museum studies. His exploration of Louisbourg, Upper Canada Village, Sainte-Marie among the Hurons, and many other living history sites tells us much about how Canadians desired to recreate the past in a changing and modernizing world. Gordon also unpacks the intersection of tourism, regional development, and the challenges of historical reconstruction (such as picking a time period in which to place historical animators for sites that span decades or centuries).

Andrea Terry’s Family Ties is a more limited book. She examines three historic houses that are now museum sites: Dundurn Castle in Hamilton, William Lyon Mackenzie House in Toronto, and Sir George-Étienne Cartier National Historic Site in Montreal. Terry skilfully analyses how artifacts, programming, and animators infuse the stories told in these spaces, as well as how the past is actively reshaped in the present.

While Gordon’s Time Travel is an easy read underpinned by research into several archives, Terry’s work is steeped in theoretical discussions where the reader is subjected to page after page of quotes from other scholars. Some of these discussions burden the story, and the reviewer wished for a broader study that included well-known and contested history sites like Riel House in Winnipeg, Bellevue House in Kingston, Ontario (where Sir John A. Macdonald lived), or Laurier House in Ottawa.

These living history sites and historical houses are places where the past is performed. Yet with tourism dollars driving many of these museums — hence Gordon’s clever title — the history is often sanitized, even sanctified. Visitors do not encounter eighteenth- or nineteenthcentury living history actors dying from a runaway infection that cannot be treated in an age before antibiotics.

In this new century of social mediadriven news and events, where everyone is connected and at the same time disconnected, these sites, houses, and museums allow us to return to a quieter time, to marvel at how the past was (or how we think it was), and to visit, if temporarily, a different way of life — some of which is familiar, while other parts are foreign.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement