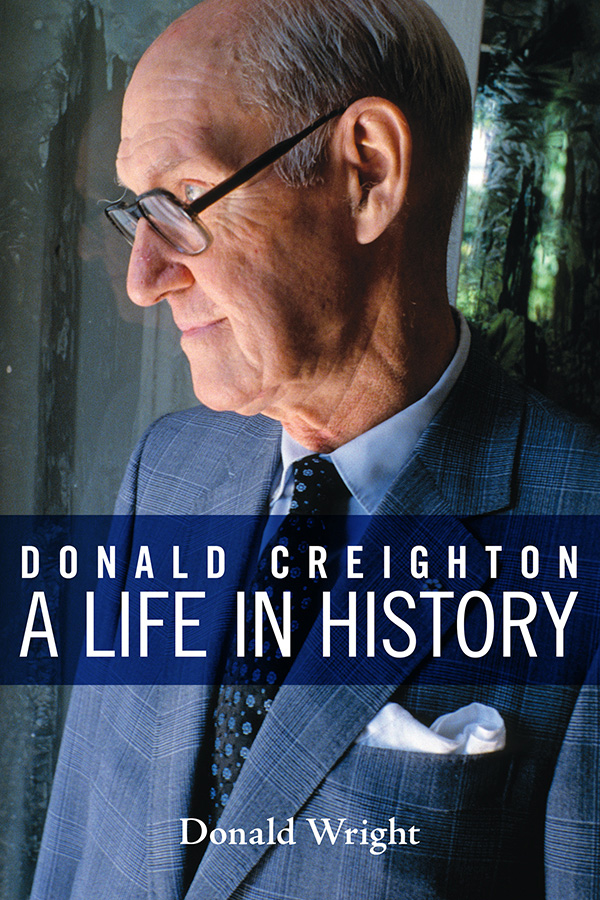

Donald Creighton: A Life in History

Donald Creighton: A Life in History

by Donald Wright

University of Toronto Press

490 pages, $37.95

Donald Creighton (1902–1979) wrote about the history of Canada “as if it mattered.” Biographer Donald Wright suggests that Creighton also matters and has produced an engaging portrait of a scholar and public intellectual who dominated his profession at mid-century but who came to be seen as quaint, even embarrassing, by many colleagues.

Wright tells the story of this complex and pivotal figure with sensitivity, respect, and a sharply critical understanding of his subject’s self-inflicted shortcomings. Creighton’s origins help to explain him: the proper Methodist upbringing in Edwardian Toronto (where “‘God, king, and country’ was not an empty phrase”), a classical education at Victoria College and Oxford, and the honing of an argumentative mind.

At the University of Toronto, Creighton rose professionally in “a department marked by strong personalities, ancient animosities, ambitious juniors, and brewing resentments.” He scrambled for research funding, mostly in the U.S., carried a heavy teaching load, and strove to construct a vision of Canada that explained its history and gave it meaning.

This vision — Creighton’s “Laurentian Thesis” — saw Canada as the product of its geography, from the St. Lawrence River and Laurentian Shield westward by rail to the Pacific. At the same time, Britain’s imperial, commercial, and military ties to Canada forestalled the country’s absorption by the United States. These twin realities, and not an urge to emulate the U.S. by separating from Britain, gave Canada its distinctive nationality and its reason for being in North America.

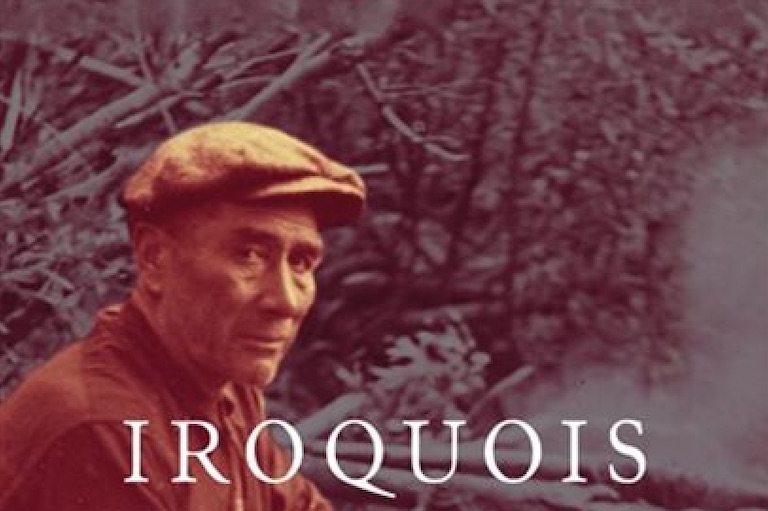

In his book The Commercial Empire of the St. Lawrence and his two-volume biography of Sir John A. Macdonald, especially, Creighton fleshed out his very British framework of Canadian history. But Creighton’s “Achilles heel,” says Wright, was always his dismissal of the role of French Canada and First Nations people. Within his mythic framework, a form of “intellectual imperialism,” they didn’t count or were simply obstructions.

As Canada became a multicultural and bilingual nation after the Second World War, more aligned with the United States than a diminished Britain, Creighton stuck ferociously to his vision. Wright portrays Creighton as a stalwart product of his time — one for whom the new flag was another sacrilege — and offers an unflinching depiction of a great historian who “was always more comfortable in the nineteenth century than he was in the twentieth century.”

Wright admires Creighton’s scholarly and literary gifts. While thoroughly professional in his research, Creighton regarded history as a field of literature. His focus was on “a story to be told,” with a vivid narrative flow. As Wright stated in his entry on Creighton in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, “among his contemporaries no other historian wrote as well or reached as many readers.”

History was akin to another art form, says Wright. Creighton admired Wagner’s operas, and his eleven books feature vast themes, heroic figures, sinister villains, and recurring motifs. By the 1970s, however, an embittered Creighton sensed impending twilight for Canada. He anticipated a tragic Wagnerian conclusion, with a divided Canada falling prey to cultural and economic takeover by the U.S.

Wright, an associate professor at the University of New Brunswick, has “lived” with his subject for years and is the master of this material. (He owns and uses Creighton’s rustic writing desk, for example.) Wright also understands the importance of Creighton’s wife, Luella, herself a published author. Her role is given full weight, including her own bibliography.

In this highly accessible biography, organized around the four seasons, Wright gives Creighton his due as an undeniably salient figure in Canada’s intellectual history. In the process, he has created an invaluable guide for anyone who seeks to read and to understand Canada’s pre-eminent historian.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement