Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

The Bear Facts

-

Lieutenant Harry Colebourn with Winnie at Salisbury Plain military training camp in England, circa 1914.Library and Archives Canada

Lieutenant Harry Colebourn with Winnie at Salisbury Plain military training camp in England, circa 1914.Library and Archives Canada -

Two children and Kenelm and Theresa Quincy and feed a bear cub in Vancouver, circa 1910.City of Vancouver Archives

Two children and Kenelm and Theresa Quincy and feed a bear cub in Vancouver, circa 1910.City of Vancouver Archives -

A polar bear cub is photographed wearing snow goggles on Southhampton Island, Nunavut, circa 1942-44Library and Archives Canada

A polar bear cub is photographed wearing snow goggles on Southhampton Island, Nunavut, circa 1942-44Library and Archives Canada -

Bear cubs on a signpost at Mount Robson, Alberta, circa 1920s.Library and Archives Canada

Bear cubs on a signpost at Mount Robson, Alberta, circa 1920s.Library and Archives Canada -

Nancy, a pet grizzly bear, at the CPR station in Medicine Hat, Alberta, circa late 1890s.Esplanade Archives of Medicine Hat

Nancy, a pet grizzly bear, at the CPR station in Medicine Hat, Alberta, circa late 1890s.Esplanade Archives of Medicine Hat -

A black bear poses with people on the verandah of the CPR hotel at North Bend, British Columbia, circa 1887 or 1888.City of Vancouver Archives

A black bear poses with people on the verandah of the CPR hotel at North Bend, British Columbia, circa 1887 or 1888.City of Vancouver Archives -

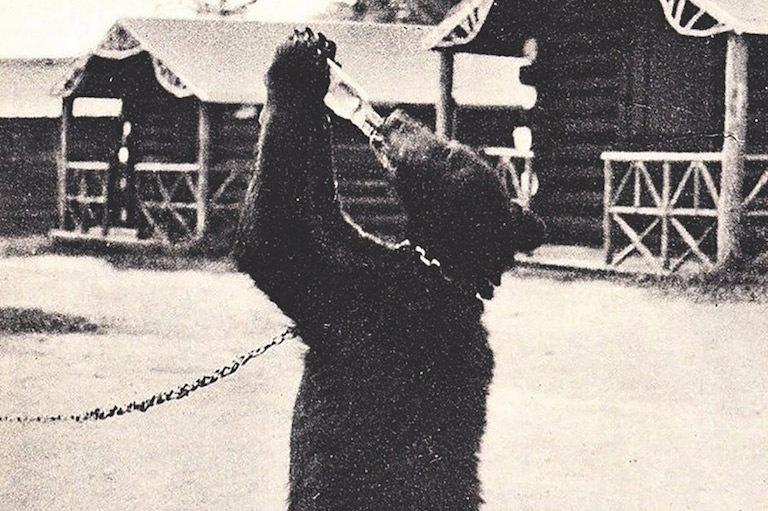

A chained bear guzzles a soda at Dorchester, New Brunswick, circa 1930s.Ben Bradley collection.

A chained bear guzzles a soda at Dorchester, New Brunswick, circa 1930s.Ben Bradley collection.

Winnie the bear, the real-life inspiration for the classic children’s stories about Winnie-the-Pooh, certainly did not have the life of a typical Canadian bear. Yet, while her story was exceptional in certain regards, in others it was far from singular.

Winnie was initially taken from the forest near White River, Ontario, by a trapper who had killed her mother. The trapper brought the orphaned cub into town and sold her to Lieutenant Harry Colebourn, a soldier who was travelling through town aboard a train that would carry the bear further afield. Winnie became a mascot at a First World War training camp in Britain and later was given to the London Zoo when Colebourn went to fight in France.

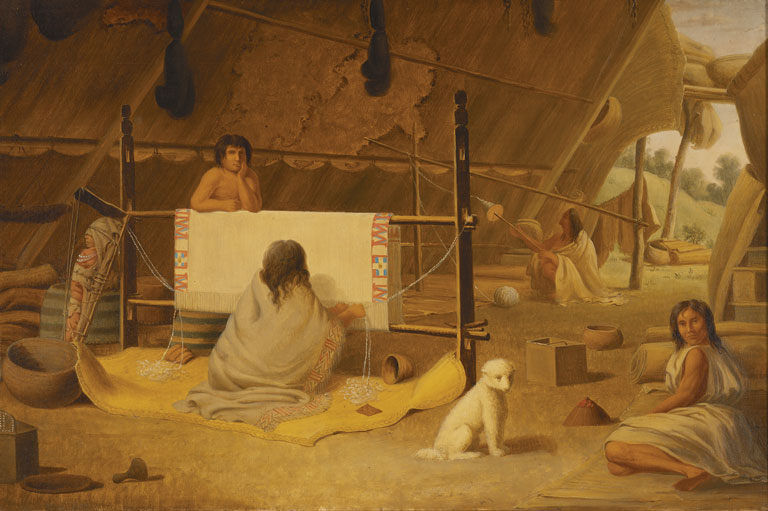

Similar instances of bears being captured, transported, and then used as pets, mascots, and attractions abound in Canadian history. In fact, doing so was a fairly common practice and a part of popular or vernacular culture from the late-nineteenth century well into the twentieth. It happened from coast to coast to coast in an array of settings, including hinterland work camps, rural farms and ranches, small-town stores and hotels, and even urban homes.

Few bears were taken as far or written about as much as Winnie was, and therefore most of their captivity stories are forgotten to history. Nevertheless, the ways Canadians used bears as companion animals, promotional devices, and tourist attractions reveal how values and premiums placed on wildlife have changed over time.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

Many bears that fell into the hands of hunters, farmers, and hinterland resource workers were brought to communities where they were displayed at commercial businesses, hotels, and railway depots. Typically they were used to attract and to amuse customers by appealing to their curiosity about wild animals.

The CPR made Western Canada accessible to well-heeled pleasure travellers, and several of its station masters offered passengers the opportunity to see bears up close. Photographs from the 1890s show a yearling black bear displayed on the veranda of the Fraser Canyon House hotel at North Bend, British Columbia. Around the same time, a grizzly bear named Nancy was kept at the station in Medicine Hat, Alberta. Nancy was a prominent trackside feature due to her pen being attached to the garden beside the station platform.

Tourists hoped — or even expected — to see bears in Canada’s mountainous national parks, and the CPR sometimes helped them fulfill this wish. Bears were also held captive at points along the Canadian National Railway, particularly along its route through the Rockies.

While passenger trains followed fixed routes and predictable timetables, the age of mass automobile tourism that began during the interwar years saw travellers explore Canada at their own pace and by routes of their own choosing. Since many motorists hoped to see large, furry mammals “in the wild” when travelling Canadian roads, putting captive bears on display at roadside businesses struck many operators as a surefire draw.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

Most human-bear encounters at roadside businesses were benign. However, having noisy children, giddy tourists, and city people unfamiliar with wild animals in close quarters with bears could sometimes lead to significant injury and even death. Nevertheless, against the experts’ advice, proprietors of roadside businesses in Ontario and other provinces continued using bears to attract customers.

The practice of keeping bears captive at roadside stopping places only began a gradual decline in the 1950s, as Canadians recognized the dangers and liabilities of displaying these animals. There was also a broader change in attitudes toward wildlife spurred by suburbanization, the ecology movement, and the popularity of movies like Walt Disney’s Bambi.

Whether at trackside stations, at roadside businesses, or in the family home, the private keeping of bears as “pets” was a highly unusual and blurred traditional relationships between humans and companion animals. Some bears fell into captivity after being rescued by good-hearted people who could not stand to leave orphaned cubs in the wild. Others were taken from similar circumstances by profit-minded individuals, and still others were hunted down with the specific intention of their being made a captive. But regardless of how a bear came into captivity, a sad fate awaited most that did. Captive bears that showed signs of aggression, caused accidental injuries, or learned to escape were likely to be passed on to another owner, released back into environments to which they were unaccustomed, or killed.

Our relationship with bears has changed for the better, overall, and we have become both better informed and more compassionate in our dealings with them. Canadians no longer think of bears as viable candidates for captivity as pets or attractions; most believe their rightful place is in the wilderness, sometimes with protective measures. But although the practice of ordinary Canadians keeping bears as pets and mascots has fallen by the wayside, what lives on is the public’s desire to observe bears — in the wild, beside a highway, in zoos and wildlife parks, on the printed page, and online. Looking beyond Winnie to the broader history of how Canadians have kept bears in cages, on chains, and in backyard pens goes some way toward explaining our continuing fascination with these animals and, ultimately, elucidating our own human nature.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Nominate an exceptional history project in your community for this year’s Governor General's History Award.