Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Behind the Lens

When I was a rookie reporter for a small daily in Nova Scotia, I was also required to shoot my own photos. I still remember my first breaking news assignment like it happened yesterday.

The scanner crackled the news: a collision near the town's busiest intersection, a pedestrian down … injuries unknown.

I grabbed my battered old Pentax K-1000 and rushed for the door.

Soon, I pulled up to the scene. There were ambulance lights flashing, and a woman on the ground, moaning in pain. Nearby, the driver of the car seemed dazed as he recounted the events to police.

I remember moving in close to get a good photograph of the woman. Pure mechanics took over: frame the photo, focus, press the shutter release, repeat.

The victim, still conscious, stared straight into my lens. I kept on shooting. Then, just as suddenly, it was over. As the ambulance sped away, I hurried to get my film processed before deadline.

At the time, it didn't cross my mind to put down my camera and offer my assistance. Today, years later, I wonder if I made the right choice.

I have long admired photojournalists; admired, but not envied them, for theirs is a lonely occupation. While most of us participate in life, photographers are required to be outsiders. They exist on the fringes, viewing life through lenses that provide both sharp focus and cold distance.

Two years ago, we presented in The Beaver a special magazine feature titled “10 Photos that Changed Canada”

As I read through the articles, one line in particular stayed with me. It's from Chris Webb's story “Henderson's Goal” — the tale of Frank Lennon's iconic photo, taken moments after Team Canada scored the winning goal in the 1972 Summit Series against the Russians.

The game was in its dying seconds. Lennon — at the time a shooter for the Toronto Star — stood silently near the Russian goal amid thousands of frantic fans. When Paul Henderson banged home his own rebound, the Canadians in the crowd erupted with euphoria — but not Lennon.

As Webb recounts: “Lennon desperately wanted to join in the cheering but stayed perfectly still shooting the celebration.”

If I'd been there, I would have likely whooped as loudly as the rest — and likely missed the photo. That's why I'm not a great photographer.

To be a great photographer requires sacrifice. Consider Claude Detloff, the Vancouver Province shooter who took the photo at the heart of Phil Koch's article “Wait for me, Daddy.” The photo shows a mother chasing her son as the lad — hand outstretched — reaches for his father who is marching off to war.

To me, the image is gut-wrenching. I wonder: did Detloff wish, even momentarily, that he could toss aside his camera and instead console the little boy? He didn't — and for that, we are all lucky.

Great photographers must view the world dispassionately in order to fill their photos with passion. Their cameras and press cards gain them entry into an exclusive world many of us will never know — a world where prime ministers pirouette behind queens and political campaigns are lost with a simple slip of a football. Yet, while a party to this world, they are never truly part of it.

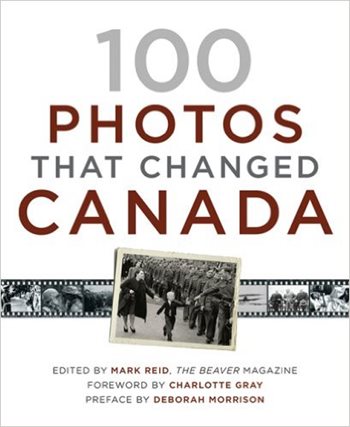

In the wake of the “10 Photos that Changed Canada” feature, we produced a book, titled 100 Photos that Changed Canada, which hit bookstores in November 2009.

In it, you'll find photos that inspire and infuriate, make you laugh, and cry. Each photo is a shared moment in time that collectively makes up the fabric of Canada.

As you leaf through the pages of the book, please take the time to reflect on the photographers who sacrificed a bit of themselves to capture Canada's iconic images.

We're fortunate that some among us choose to live this lonely life.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.