Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Confederation: The Unfinished Project

Grade Levels: 5/6, 7/8, 9/10

Subject Area: Social Studies, History, ELA, Civics

This lesson plan is inspired by the article “Confederation Diary,” in the Summer 2017 issue of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

Lesson Overview

This lesson examines the various viewpoints and perspectives of the participants in the Confederation debates, including the voices of women, Indigenous peoples and other groups left out of the process. Using primary source material, students will be asked to interpret various perspectives on Confederation as well as to imagine how discussions could look today, set within contemporary values.

Time Required

45 minutes x 5

Historical Thinking Concept(s)

This lesson plan uses all six historical thinking concepts. This includes: establish historical significance, use primary source evidence, identify continuity and change, analyze cause and consequence, take historical perspectives, and understand the ethical dimension of historical interpretations.

Learning Outcomes

Student will:

- Outline the major participants in the Confederation debates of the 1860s, as well as identify the the principal groups who were excluded.

- Summarize the point of view of one of the provinces or parties involved in the debates, including pros and cons of joining the union.

- Describe some of the major ideas informing Confederation debates.

- Explain the concerns of groups not included in the debates, including linguistic minority groups, women, and First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people.

- Apply their new understanding of the Confederation debates to create their own political cartoon, illustrating a distinct point of view on the union.

- Analyze how the debates over nationhood, inclusion and identity have by identifying those who might be included in a discussion of Confederation if held today.

- Recommend a new model for contemporary Confederation that is more inclusive and reflective of Canada today.

Background Information

At the end of the summer of 1864, delegates from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island gathered in Charlottetown to discuss the possible union of the Maritime colonies. The Canadian delegation — led by John A. Macdonald, George Étienne Cartier and George Brown — invited itself to their meeting. The Canadian delegates did their best to persuade their counterparts of the benefits of an extended union and debated the main points of their initiative with the Maritime delegates.

Having come to an agreement on the principle of a colonial union, the delegates decided to pursue the discussions in Quebec City. In October 1864, they met in the library of the Parliament of the Province of Canada to debate two major visions: one favouring a strong central government and the other upholding the autonomy of the provinces.

At the second conference, 72 resolutions were adopted. They were essentially a draft constitution. At the end of the Quebec Conference, the delegates were asked to have the resolutions ratified by the legislative assemblies of their respective colonies. The process of ratification was not without friction. As these publications suggest, Confederation was intensely debated in the assemblies and newspapers. In Nova Scotia, Joseph Howe opposed the union initiative in a series of open letters entitled “The Botheration Scheme.” Other politicians and journalists published vehement pamphlets. However, Thomas D’Arcy McGee, in Montreal, and Edward Whelan, in Charlottetown, eloquently defended the Confederation initiative.

A third conference began in London, England, on December 4, 1866. Ratified by the legislative assemblies of the Province of Canada, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, the 72 resolutions of the Quebec Conference now had to be revised and validated by the imperial government. A bill entitled the British North America Act, essentially a written constitution, was introduced in both houses of Britain’s Parliament and approved. Queen Victoria then received the delegates at court and, on March 29, 1867, gave royal assent to Confederation.

Confederation was a union of colonies who considered themselves to be as different as countries vast distances apart. Yet, not all nations in the land that was to be called Canada were included. First Nations had long signed treaties with the government to preserve friendship and goodwill. For First Nations people, the agreements they signed were contracts that should last forever, or as long as the sun shines and the rivers flow. First Nations, along with their lands, were mentioned in the 72 resolutions as subject to the jurisdiction of the central government. The Resolutions, as well as the British North America Act which created Confederation, did not name First Nations as nations unto themselves. Confederation was signed without their understanding or consent, leading the way to future abuses of rights.

In addition, Confederation was not a union of diverse people. At the time of Confederation in 1867 women were not allowed to be politicians. They were not even allowed to vote in federal elections. It was not until 1918 that women could vote in federal elections, and not until 1919 that women gained the right to be elected to the House of Commons. Most men believed women were incapable of participating in democratic affairs. At the Charlottetown, Quebec and London conferences, however, women accompanied their husbands and fathers. The women played a major role in the social aspects of the conferences. Mercy Ann Coles, who accompanied her father from Charlottetown to Quebec City, carefully recorded her impressions of the events in her diary. Sarah Caroline Steeves, daughter of a delegate from Nova Scotia, is said to have made a cushion with silk from a gown she wore to the conference balls in 1864. Still, and despite these voices, it is clear that the perspectives of women did not feature prominently in the shape the country was to take.

Confederation was instituted as a union of the provinces with the aim to promote economic opportunity and security and well-being for the provinces, as well as to ensure the development of a national railway system. It was not a compact for or of the people, but an agreement that the provinces arrived at through negotiation and compromise, by considering what was best for them.

The Lesson Activity

Activating

- Working in pairs or in small groups (3-4), students will share any information they know about how Canada was founded. If no one in the group has prior information, students will create a bullet-point chart showing what they think happened. Groups should then share their version of events with the rest of the class.

- Students will watch the Heritage Minute. Breaking into pairs or groups, they will be asked to revise the information or the stories they created according to the information provided in the Heritage Minute.

Acquiring

- In small research teams, students research basic information on Confederation – who, what, when, where, why? (Student Handout 1 and Confederation for Kids website)

- Teacher presents political cartoon, “La Confederation!” (Annex 1). The class can predict who they think drew it and what it might mean, before it is explained by the teacher.

(The cartoon, published in Quebec in 1864, paints Confederation as the harbinger of destruction. The sacrificial lamb in the image represents Québec as a sacrifice to the hydra monster of Confederation, which is ridden by George Brown, one of the Fathers of Confederation. The cartoonist predicts the demise of French Canadian culture, and shows Québec politicians blessing the monster instead of defending the lamb. The accompanying text for this cartoon argues that Québec will be destroyed by joining Confederation. It represents the total destruction of Québec’s cultural, religious, and linguistic heritage.)

- Students read “Confederation Diary” considering the perspectives of women left out of the Confederation debates.

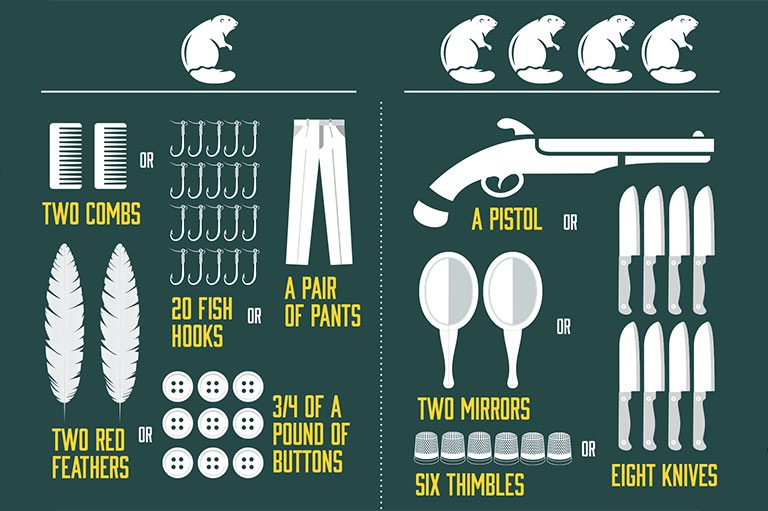

- Teacher presents treaty medal (Annex 2). The class can predict what the imagery seems to represent and what it might mean, before it is explained by the teacher.

(Between 1871 and 1921, the Crown concluded 11 numbered treaties with groups located in the territorial boundaries set by Canada. First Nations leaders believed that the Treaty they were signing was establishing a nation-to-nation relationship, negotiated as equals, that would ensure the group’s survival and success into the future.)

- As a small group or as a class, students brainstorm what other groups might have been left out of the Confederation debates.

Applying

- Using the summary perspectives attached, students will produce their own political cartoon outlining their province or territory’s objection to, or agreement with, Confederation (according to the perspective based on the handouts).

- Students will watch the original Heritage Minute again, noting what they might change to better reflect the diversity of Confederation debates and the difficulties of achieving consensus.

- Students will engage in a small or large-group discussion about which groups might be invited today to discuss Confederation, if the debate was to take place in contemporary times.

Suggested Materials/Resources

“Confederation Diary,” in the Summer 2017 issue of Kayak: Canada’s History Magazine for Kids.

Heritage Minute: Sir John A. Macdonald

Annex 1: Confederation Cartoon

Annex 2: Treaty Medal

Themes associated with this article

Related plans and resources

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!