You Don't Vote for Kings

Legitimate political power derives from a mandate from the masses — that’s today’s theory. But in practice, Canada’s governing elites historically have often tried their best to snub the masses.

The road to today’s universal adult franchise has been not only incremental, it’s often been corrupt, violent, and not awfully democratic.

What helped women earn the right to vote in federal elections in Canada in 1918? Was it forward thinking politicians intent on embracing high-minded, democratic ideals?

Sadly, no — it was nothing short of political scheming, a kind of gender gerrymandering. In 1917, Prime Minister Robert Borden felt he could save Canada’s honour only by winning that year's general election, so he rigged the vote to ensure that he would.

Borden’s Conservative government extended the franchise to people most likely to support his policies and took it from those most likely not to.

As one critic remarked, it would have been more honest if the legislation “simply stated that all who did not pledge themselves to vote Conservative would be disenfranchised.”

Arthur Meighen, the federal solicitor general, wrote to Prime Minister Borden, suggesting that extending the franchise to women could meet the “foreign population difficulty.”

Meighen wasn’t enthused about giving women the vote but hoped it would bolster election ambitions: “To shift the franchise from the doubtful British or anti-British of the male sex and to extend it at the same time to our patriotic women, would be in my judgment a splendid stroke.”

He suggested giving “the closest consideration to this subject.” A year later it was law.

Borden’s government needed as many “patriotic women” as it could get to win the election. In 1917, the war in France was killing and wounding men faster than the Canadian army could replace them.

Borden decided conscription was the only answer. If men wouldn't volunteer to fight, they’d be forced to.

Quebec was generally against conscription — for many reasons.

For one, it saw little reason to participate in a foreign war, particularly if it appeared to be at the bidding of the English. Borden was going to lose almost every seat in that province, and the outlook in the West was just as unpromising. Farmers didn’t want to lose sons to conscription, and the West was full of recent immigrants who tended to vote Liberal.

Clearly something had to be done. On September 25, Borden wrote in his diary, “our first duty is to win, at any cost, the coming election in order that we may continue to do our part in winning the War and that Canada be not disgraced.”

So Borden and the Conservatives pushed two laws through Parliament: the Military Voters Act and the Wartime Elections Act.

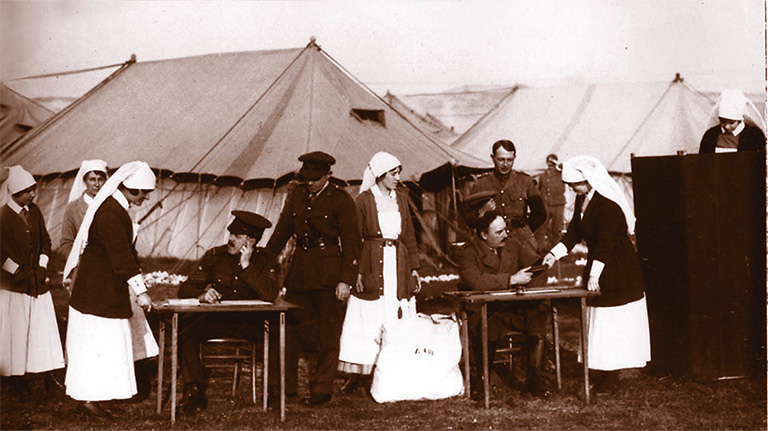

The first gave the vote to “all British subjects, whether male or female” who were in the armed forces. In one stroke, about two thousand army nurses became the first women to get the federal franchise.

The act also allowed military personnel to vote simply by party, allowing votes to be counted where a party needed them most.

The Wartime Elections Act gave the vote to women related to Canadian or British military or naval personnel and took it away from Canadians naturalized after 1902, if they were from a country Canada was fighting.

One result? Many of those Liberal immigrants in the West were disenfranchised.

Margaret Gordon, president of the Canadian National Suffrage Association, said it would have been more honest to make it illegal not to vote Conservative.

Borden’s next step was to form a Union government, with the Conservatives taking in Liberals who either supported his policies or realized they couldn’t win if they appeared not to.

A vote for the Liberals was depicted as a betrayal of the country’s fighting men. The military voted 92 percent for the Unionists, and anecdotal evidence suggests “patriotic women” did their bit, too.

On the December 17 election day, the Winnipeg Evening Tribunereported that Mrs. M. Wilson and her three female friends cast their votes as expected: “We have done all we could to put the Union government back into power.”

The Unionists won 153 seats, including 14 decided by the military vote. The Liberals got 82, including 62 of Quebec's 65.

Borden's campaign promised all women the federal vote and, in 1918, they got it. By the early 1920s, women also had the provincial vote everywhere but Quebec, which resisted the inevitable until 1940.

The immorality of Borden pushing such acts through was stunning in its transparency, but rigging a vote was nothing new in Canada. Extending the franchise had little to do with the political desire to protect basic human rights.

Woman weren't the only disenfranchised group, as voting restrictions were linked to wealth (or, lack of it), religion, ethnicity, and, though still a contentious issue, even incarceration.

Today, most Canadians take it for granted that all adult citizens have the right to vote. But in the nation’s early days, those who had voting privileges were in the minority.

In 1885, the Canadian Parliament established a complicated federal franchise based on property ownership. At first, only men could vote — but only some of them.

Political resistance to extending the franchise reflected a distrust of liberal-democratic ideals and a general protective attitude - the few privileged voters would have equated universal suffrage with social disorder.

After all, landowners had a reason to uphold traditional values, to not “rock the boat.” Teems of newcomers — many with no land at stake — couldn't be entrusted with the vote. Or so went the prevailing attitude.

Chiselling away at such entrenched attitudes took years though the history of the vote in Canada is almost entirely one of a constantly expanding franchise with small detours along the way.

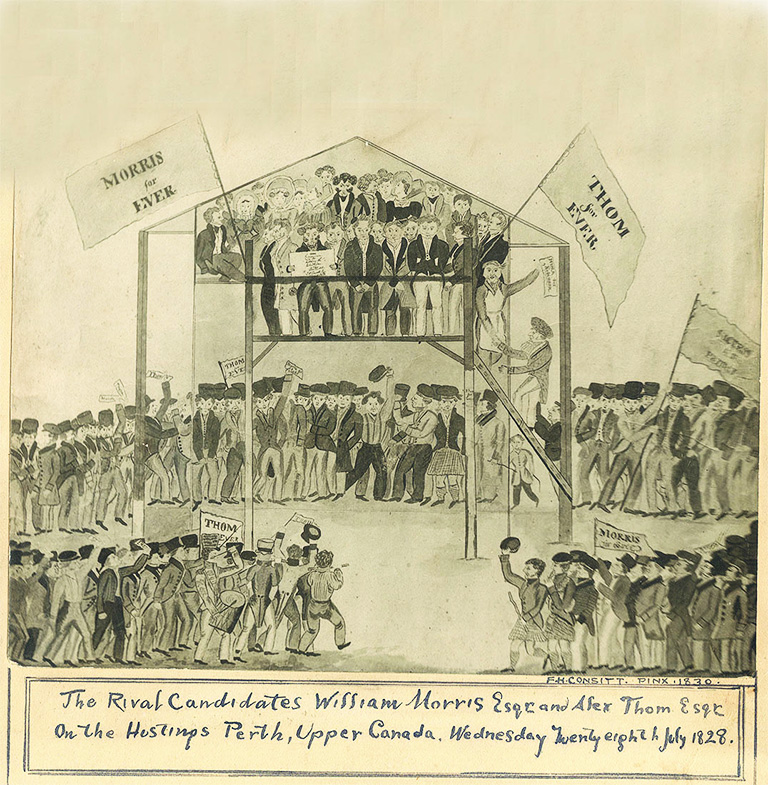

More than one hundred years before the federal franchise, simply preserving life and limb could be an obstacle. Some of the first changes to the rules were aimed at reducing election violence.

Election rules for Britain's Canadian colonies — beginning with Nova Scotia in 1758 — were blueprints for fraud, intimidation, discrimination, rioting, and even murder.

Casting a vote in private was almost unimaginable.

Instead, voting was conducted aloud, and “the franchise-holder had to step up before a turbulent crowd of friends and foes ... and openly declare his choice, while enemy partisans tried to howl him down or more vigorously discourage him,” wrote historian J.M.S. Careless. “Hotly contested elections thus all too easily degenerated into pitched battles of fists, cudgels and stones - and sometimes gunshots and death.”

Candidates fuelled the mayhem with free liquor, and by Confederation in 1867, at least twenty people had been killed in riots.

In 1785, New Brunswick’s first election produced its first election riot. That was in the Saint John riding, where six pro-government candidates, including the attorney general, were known as Upper Covers (landowners in the Upper Cove region).

They were opposed by Lower Covers, voters unhappy with the way land was handed out, among other things.

Voting began in a Lower Cove tavern and was interrupted by the riot that started after Sheriff William Oliver moved the poll to an Upper Cove tavern. The Lower Covers won all six seats, but Upper Covers demanded a recount.

The sheriff, who had voted for them, agreed, and together they threw out almost two hundred votes on the grounds that those who cast them did not meet a three-month residency requirement. That excluded about one-third of the Lower Cove voters, more than enough to reverse the election result.

The same election was also manipulated on religious grounds, as the votes of thirty Acadians in Westmorland County “were objected to as illegal, the Frenchmen having refused to take the oath of abjuration,” the Royal Gazette reported.

The oath required Catholics to pledge allegiance to the king and renounce the authority of the Pope. Not likely. So with handfuls of votes discounted, on January 20, 1786, the Westmorland candidate who had initially finished last gloried in his win.

But sheriffs were not alone in determining who could vote. Property ownership was a clincher. In 1855, provincial attorney general Charles Fisher reflected on the rationale for property rules.

A person with money or property “would not be likely to wish to see the laws and the institutions of the country disregarded.”

Property requirements persisted into the twentieth century, and the man in charge of deeds could be a candidate’s best ally (as he provided proof of voting eligibility). Such support was particularly handy when the man in charge of deeds was your father, as in the Nova Scotia election of 1806.

In this case, Edward Baker won in Amherst riding with the help of Edward Baker Sr., according to a petition to the House of Assembly by the losing candidate.

The man in charge of deeds was small potatoes when it came to rigging a larger election.

In that case, the person to see was Charles Edward Poulett Thomson, 1st Baron Sydenham, the governor general who predetermined the outcome of the 1841 vote in the Province of Canada.

“He chose returning officers favourable to the government, issued land deeds to supporters and denied them to opponents, thus disenfranchising the latter, handed out promises of pensions and government patronage ... and distributed polling booths and troops where they would most benefit his sympathizers,” according to Canadian historian Phillip Buckner.

Sydenham got down to rougher business, bringing in thugs at polling stations —nine people were killed in the 1841 election.

The baron had been sent to Canada to get local backing for the British government's plan to unite the two colonies, thus ending the French-English divide by assimilating the French in the new, larger colony.

Sydenham proclaimed the union on February 10, 1841.

The next job was to get the colonials to elect a supportive government. Elections were set for March and April. “In Upper Canada they will be excellent,” Sydenham wrote, “In Lower Canada we shall not have a man returned who does not hate … everything which has a taint of British feeling.”

His plans to rig the outcome included the tough job of finding pro-British candidates, and the easier one of gerrymandering electoral districts to ensure voters were pro-British: “I shall reduce the limits of Montreal & Quebec to the Cities & cut off the suburbs” (the suburbs were mostly French, which largely disenfranchised the French, because these areas became rural ridings where tenants did not have the vote).

There was only one poll to a riding, and in largely French areas, Sydenham put the polls in English-speaking enclaves, then sent out mobs to prevent the French from using them.

One French-Canadian leader, Louis Hippolyte Lafontaine, withdrew his candidacy rather than have his supporters risk trying to vote. Sydenham supporters won the election.

Qualifications governing the right to vote differed among provinces and governments. Finally, in 1920, Parliament took control of the federal franchise with the Dominion Elections Act (renamed the Canada Elections Act in 1951).

Property requirements for voting in federal elections had ended, but racial and religious exclusions remained. Anyone barred on those grounds from voting provincially was also barred from voting federally. In both instances, British Columbia was centre stage.

British Columbia’s white settlers worried about being outnumbered by the growing Asian population. The gold rush of 1858 had spurred the influx of Chinese, and Japanese arrived about twenty years later.

Both groups were denied the vote (if they lived in B.C.) and by the 1920s, immigration barriers reduced Asian newcomers to a trickle. Despite this, fears accelerated during the Depression.

Then in 1942, disaster after disaster followed the disaster of Pearl Harbour. The Japanese who lived in British Columbia — 22,000 out of 23,000 living in Canada — were moved to internment camps.

Two years later they lost the vote, even though they no longer lived under B.C. election laws.

On July 18, 1944, with the headline “No Votes for Japs,” the Sun beamed, “There will be widespread approval in British Columbia of the decision by the Parliament of Canada to deprive the Japanese of the right to vote in the next federal election.”

War also brought religious exclusions. In 1917, the Wartime Elections Act disenfranchised conscientious objectors, or anyone who refused to go to war. Paradoxically, war later played a part in religious groups regaining the vote.

The horrors produced by racism during World War II made many people less accepting of discriminatory practices. British Columbia restored the franchise to Mennonites and Doukhobors, who had lost the vote around World War I.

First Nations, Inuit and Metis have also been targets of discrimination. In 1920, Indigenous peoples who served in the war got the federal vote, as did people who moved off reserves.

In 1950, people on reserves also got the federal franchise, but only if they waived treaty rights, including tax exemptions. By 1960, those waivers were removed.

Those steps left one sizable group without the vote, the 35,000 or so inmates of provincial and federal jails. Their exclusion could be traced back to Edward III, King of England until 1377.

Serious crimes meant civil death, he decided, and convicted felons lost civil rights. About 600 years later, some Canadian felons challenged his view.

In 1993, Parliament gave the vote to prisoners serving less than two years. That was too little for, among others, Richard Sauve, a Satan's Choice biker sentenced to life for murder.

On October 31, 2002, the Supreme Court of Canada agreed with him, allowing all prisoners to vote.

Chief Justice of Canada Beverley McLachlin said, “the slow movement toward universal suffrage in Western democracies took an irreversible step forward in Canada in 1982” when the right to vote was constitutionally guaranteed through the Charter of Rights.

The path to gaining the franchise has not been without struggles, but, as stated in The History of the Vote in Canada, the adoption of the Charter has been the “single-most effective move in reversing the last vestiges of discrimination.”

By 1993, the legislation that gave the vote to prisoners finally gave it to judges. Now that judges and the people they send to prison can vote, there are few left to whom to extend the franchise.

According to the Elections Canada Act, the only citizens “18 years of age or older on polling day” prohibited from voting are the chief electoral officer and the assistant chief electoral officer.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement