Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

The Evil Deeds of Dr. Cream

On the morning of November 15, 1892, thousands of anxious people gathered outside Newgate Prison in London, England, to await the imminent execution of a prisoner within.

It was the largest crowd to gather at an execution site in London since public hangings had been brought to an end in 1868, and although the disorderly group wouldn't get to witness the death of the prisoner first-hand, they were nevertheless eager to cheer his demise from afar.

As the Toronto Globe reported the next day: “Probably no criminal was ever executed in London who had a less pitying mob awaiting his execution.” That criminal was a McGill-trained physician by the name of Thomas Neill Cream.

Inside the prison walls on the morning of Cream’s execution, the mood was far more subdued. Cream was quiet and composed when he was led to the scaffold to meet the fate he had etched for himself over a long career of crime.

As various city and prison officials looked on, and hangman James Billington placed his hand on the lever that would send the doctor to his death, Cream allegedly started to speak. “I am Jack,” he began, but was cut off forever as the trap doors opened and his neck snapped in the noose.

Was Dr. Cream about to claim that he was none other than Jack the Ripper? Could it be that he, the notorious Lambeth Poisoner, was also responsible for the series of horrifying slayings that had confounded the people of London — and the rest of the world — four years earlier?

In the latter half of 1888, London’s largely impoverished East End served as a backdrop for the machinations of an unidentified madman who slaughtered at least five local prostitutes.

Nicknamed Jack the Ripper, this mysterious murderer was later deemed the world’s first serial killer, and while the Metropolitan Police never managed to identify or capture him, they had no end of leads to pursue. From a Jewish butcher and a Polish barber, to a famous artist and a future heir to the throne of England, the list of suspects was long — and it only grew longer as time passed.

Today, Cream’s name is still among those on this exhaustive list, and while he is not generally considered to be one of the more likely suspects, there is no doubt that he was capable of killing in cold blood.

Thomas Neill Cream was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on May 27, 1850. Four years after his birth, his family immigrated to Quebec, where Cream’s father, William, became manager of a shipbuilding and lumber firm located in Wolfe’s Cove, near Quebec City.

Cream, the oldest of eight siblings, followed briefly in William’s footsteps, apprenticing in the shipbuilding trade and helping out his father when the latter started his own successful wholesale lumber business.

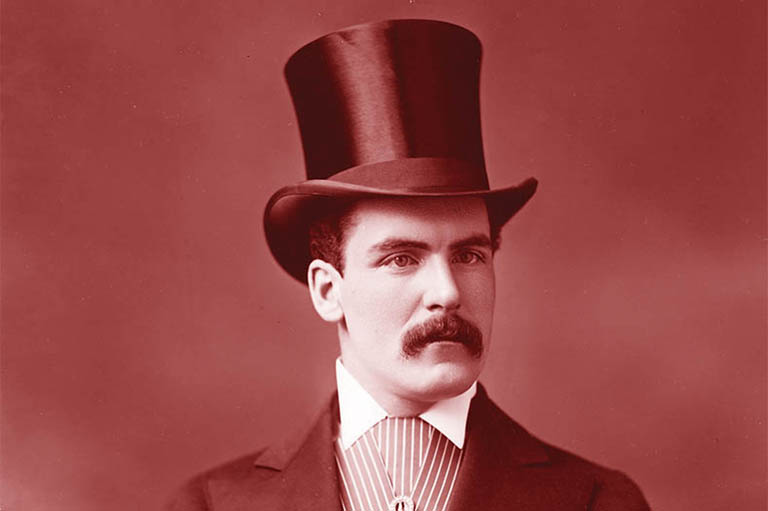

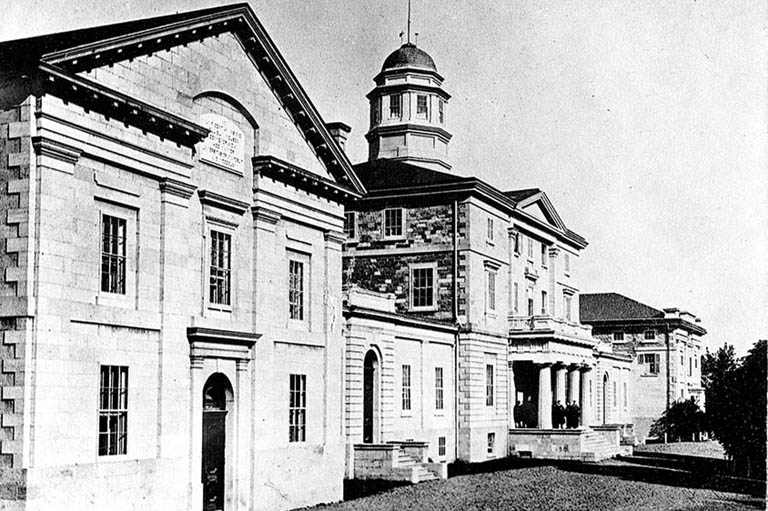

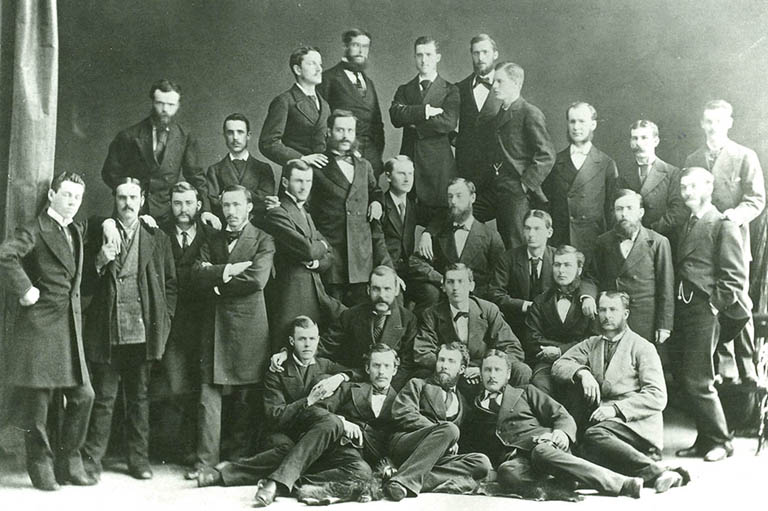

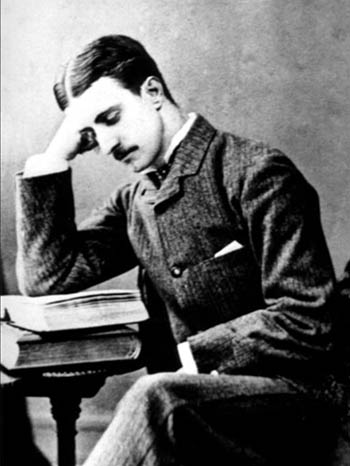

But the lumber industry did not hold Cream’s attention for long. In October 1872, at the age of twenty-two, he entered McGill University in Montreal, where he studied medicine for the next four years.

During this time, Cream earned a reputation among his schoolmates and professors as a wild and extravagant young man. Well supplied with money from his now-wealthy father, he dressed in high-priced clothing, adorned himself with flashy jewellery, and travelled about in a stylish carriage.

Despite his wild streak, Cream graduated from McGill with merit, receiving his medical degree at a crowded ceremony on March 31, 1876. The address given to his graduating class was titled “The Evils of Malpractice in the Medical Profession.”

Cream, who had written his thesis on the effects of chloroform, would soon demonstrate just how devastating these evils could be.

Not long after his graduation, Cream met and seduced a young woman named Flora Eliza Brooks, daughter of a prosperous hotel owner in Waterloo, Quebec. When Flora became pregnant with Cream’s child, Cream took it upon himself to perform an abortion.

Flora fell ill as a result, and after learning what had transpired, her father tracked down Cream, dragged him back to Waterloo, and forced him — at gunpoint — to marry her.

The next day, Cream left his new bride and headed to England to continue his medical studies at St. Thomas's Hospital in London. He attended lectures there until 1878, working intermittently as an obstetrics clerk and spending his free time courting women.

Meanwhile, back in Quebec, Flora contracted bronchitis and died of what appeared to be consumption. Her doctor, however, couldn't help but wonder if her death was actually linked to some “medicine” that Cream had purportedly sent to her.

Though he never acted on his hunch, the doctor later admitted that he suspected Cream of foul play.

Cream returned to Canada in May 1878, after spending some time in Scotland and gaining the qualification of the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons in Edinburgh. He set up a medical practice in London, Ontario, where he also began a career as an illegal abortionist.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

About a year after Cream arrived in the Ontario town, the body of a young woman named Kate Gardener was discovered in an outhouse located behind his office building. A bottle of chloroform to the body, and the woman’s death was quickly viewed as suspicious.

When it came out at the inquest that Gardener had visited Cream's office on several occasions to procure an abortion, Cream insisted that he had refused to provide her with abortifacients and maintained that her death must have been a suicide.

The coroner’s jury disagreed, ruling that Gardener had “died from chloroform, administered by some person unknown.” Though Cream was not charged with her murder, suspicions against him were so strong that both his practice and his reputation were ruined. He promptly left Canada for the wild streets of Chicago.

In the Windy City, Cream set up a medical practice near the West Side’s bustling prostitution district and was soon known to local police as a backstreet abortionist — and as someone to keep an eye on.

After narrowly escaping imprisonment for the murder of a young patient who died as the result of a botched abortion, Cream continued to draw attention from the Chicago authorities.

In December 1880, another of his patients, Ellen Stack, died after taking medicine prescribed by him. The next month, Cream attempted to blackmail the pharmacist who had made up Stack’s prescription, sending the innocent man threatening letters. The pharmacist complained to the police, but no charges were brought forth.

Finally, in 1881, police were able to put Cream behind bars for something concrete: the murder of a sixty-one-year-old man named Daniel Stott.

A resident of a Chicago suburb, Stott had been sending his thirty-three-year-old wife, Julia, into the city regularly to pick up pills that Cream had been marketing as a remedy for epilepsy.

Cream soon began an affair with the young woman and, after coaxing her to convince her husband to take out life insurance, gave her pills full of strychnine to give to him. Stott died within minutes of taking the pills.

At first, Stott’s death was attributed to an epileptic seizure. But Cream sent a letter to the coroner accusing the chemists who had made up Stott’s prescription of being responsible for the man’s demise. (Cream had intended to sue the chemists for damages on Julia’s behalf.)

When the coroner ignored Cream’s letter, the doctor went to the district attorney, who eventually had Stott’s body exhumed. Enough strychnine was found in Stott’s stomach to kill anyone three times over, but it was Cream, not the chemists, who was charged with and found guilty of murder in the second degree. He was sent to the Illinois State Penitentiary in Joliet.

In October 1872, at the age of twenty-two, he entered McGill University in Montreal, where he studied medicine for the next four years. During this time, Cream earned a reputation among his schoolmates and professors as a wild and extravagant young man.

Although Cream was given a life sentence, he was released from prison in June 1891, after having his term reduced to seventeen years and then obtaining an early parole. Upon his release, he returned to Canada briefly, then made his way back to England, eventually settling into a room on Lambeth Palace Road in South London.

Soon after his arrival in London, Cream, by then horribly addicted to drugs, began another murderous streak, poisoning four Lambeth prostitutes in the span of seven months — a fifth intended victim had wisely decided against taking the strychnine-laced pills the good doctor offered her. She later testified against him in court.

Cream could have escaped suspicion for these murders had he stayed quiet and kept to himself. Instead, he wrote letters under false names in an attempt to cast suspicion on innocent people and extort money from potential suspects.

He also bragged to others about his vast knowledge of the killings and even went so far as to take his friend, a former New York detective named John Haynes, on a tour of the murder scenes.

Police were soon trailing Cream, and he was eventually arrested and charged with the murders of four women, the attempted murder of a fifth, and the sending of letters of extortion to two London physicians.

His trial took place at the Old Bailey (London's Central Criminal Court) over five days in October 1892, and the jury needed only ten minutes to arrive at its verdict: Guilty. Justice Henry Hawkins, the presiding judge, sentenced Cream to hang, telling the prisoner that his cold-blooded deeds could “be expiated only by your death.”

Shortly before Cream was sent to the gallows, he conceded to his jailors that his sentence was deserved and admitted to murdering many other women. Since then, the notion that Jack the Ripper's victims were among these other women has been met with both interest and disdain.

The main argument against the theory that Dr. Thomas Neill Cream was Jack the Ripper seems airtight: in 1888, the year the Ripper murders occurred, Cream was securely behind bars in Joliet, Illinois, serving time for the murder of Daniel Stott. And while this simple fact has prompted most Ripperologists to dismiss Cream as a suspect, it hasn't deterred all of them.

In the summer 1974 issue of The Criminologist, late Montreal writer Donald Bell published an article titled “Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution?” in which he championed the possibility that Cream was the Ripper. Bell maintained in this article, and in another published in the Toronto Star in February 1979, that Cream could have been let out of prison long before 1891 (the year of his official release).

In the 1880s, the penitentiary at Joliet was rife with corruption among prison authorities. So, it might have been possible that Cream — whose father died in 1887 — was able to take advantage of these crooked conditions by using a portion of his large inheritance to effect an early escape and keep his jailors quiet about his absence.

According to Bell, if one is able to accept the idea that Cream could have managed a clandestine escape prior to his official prison release, then a strong case can be made that he was also Jack the Ripper.

Cream did, after all, share a major personality trait with the mysterious East End murderer: both were serial killers of London prostitutes. And while Cream’s known modus operandi was to poison his victims, Bell argued that he “was more naturally a doctor-butcher style killer than he was a poisoner.”

Indeed, Cream's past as an illegal abortionist could be seen as evidence of his tendencies toward Ripperlike butchery. As well, due to the nature of the postmortem wounds inflicted on the Ripper's victims, it is widely thought that Jack the Ripper must have had a medical background — like Cream.

When London authorities arrested Cream in 1892, it was impossible for them not to see the parallels between the poisoner and Jack the Ripper. Both killers appeared to possess a sense of moral superiority, killing prostitutes to rid society of what they considered a terrible menace. And both, it seemed, liked to write letters.

Soon after his arrival in London, Cream, by then horribly addicted to drugs, began another murderous streak, poisoning four Lambeth prostitutes in the span of seven months.

During Jack the Ripper's reign of terror, hundreds of letters were sent to the police and press, all claiming to have been written by the unidentified killer. Today, many Ripperologists believe that none of these letters were genuine. Other experts, however, maintain that the true killer was likely responsible for penning at least two, and possibly three, of them.

Soon after his arrival in London, Cream, by then horribly addicted to drugs, began another murderous streak, poisoning four Lambeth prostitutes in the span of seven months.

Nearly a century after these letters were written, a British graphologist by the name of Derek Davies compared samples of Cream’s handwriting with the handwriting on one of the “genuine” Ripper letters, and with that on one of the hoax letters. He found striking similarities between all three scripts.

In an article titled “Jack the Ripper: The Handwriting Analysis” (published in the same issue of The Criminologist in which Donald Bell first advanced his Cream theory), Davies concluded that Cream wrote “the two letters ... by using as much disguise as possible on each occasion.”

Much like the Ripper letters, the physical descriptions of Jack the Ripper are questionable at best. During the weeks in which the killer struck, several witnesses described men — or one man — seen with the Ripper's victims before their deaths. Not surprisingly, these descriptions varied considerably.

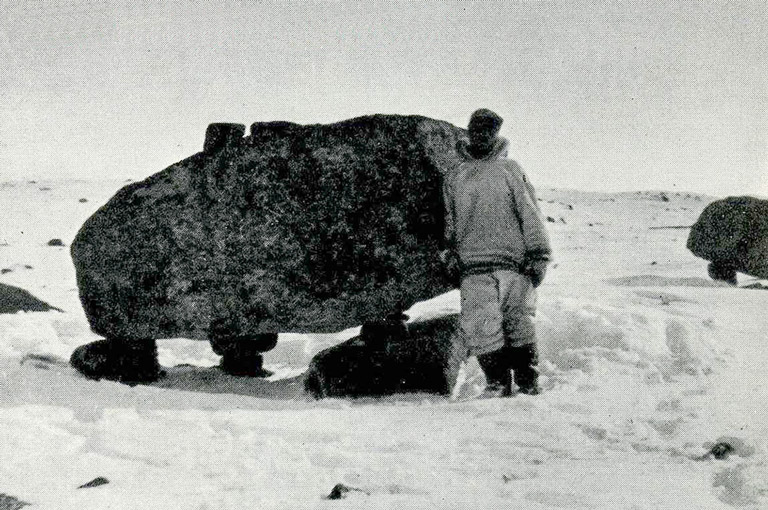

But Bell argues that the most thorough of these portraits, provided by a labourer named George Hutchinson, matched Cream's general appearance quite closely: the man had a dark complexion, a dark moustache twirled at the ends, and was sporting — among other respectable apparel — a memorable watch-chain and a horseshoe tiepin.

Lou Harvey, the prostitute who evaded Cream's attempts at poisoning her in October 1891, wrote in a letter to authorities that Cream had been wearing a fancy watch when she'd met him. And while Bell saw this as an interesting indicator, it was the horseshoe tiepin that proved to be “the turning point” in his research.

Cream was photographed wearing such a pin while he was a student at McGill University. For Bell, this was the clue that convinced him that Dr. Thomas Neill Cream could really have been Jack the Ripper.

Whether Cream was Jack the Ripper or not, the mere inclusion of his name on the list of suspects has lifted the Canadian physician to a whole new level of notoriety. And that, some speculate, is exactly what Cream had intended when he uttered, “I am Jack,” as he fell to his death.

An egomaniac who consistently sought out the spotlight, it's possible his last words were nothing more than an attempt to take credit for the murders of a more famous killer.

It's more likely, however, that Cream never uttered the words at all. Though Cream's executioner, James Billington, is said to have sworn that he heard the doctor claim to be Jack, most Ripperologists view the story as suspicious. Their doubts are supported by the fact that other witnesses at Cream's hanging never mentioned this utterance.

Regardless of the evidence for and against Cream, suspicions that Jack the Ripper once roamed the halls of McGill University have long dogged the school's medical faculty and alumni. And until the Ripper's identity is proven without a doubt, these suspicions will continue to lurk in the shadows.

History of Chloroform

While many physicians adopt their own practical “tricks of the trade” after they leave medical school, Dr. Thomas Neill Cream’s use of chloroform fell devastatingly short of therapeutic.

While at McGill University, Cream evidently recognized the colourless, sweetsmelling liquid as an effective general anaesthetic: his thesis was based on its properties and medical usefulness. It was not long before he put theory into practice.

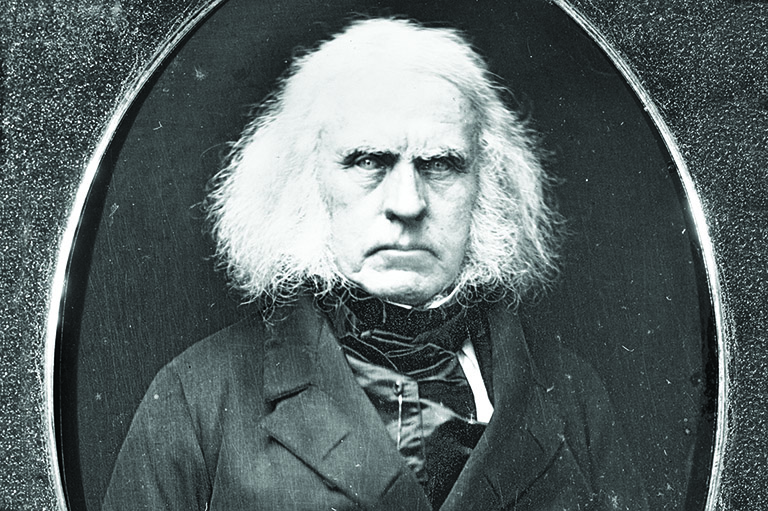

Chloroform has been known to exist for about 175 years, according to medical history. American physician Samuel Guthrie discovered the chemical compound by accident July 1831, when he mixed disinfectant with whisky.

Though independently, and just a few months later, chloroform was recognized by French chemist Eugene Soubeiran as well as Justus von Liebig in Germany. Marie-Jean-Pierre Flourens recorded chloroform’s anesthetic properties in 1847.

That same year, the chemical was used as general anesthesia during childbirth for the first time. The use of chloroform in surgery grew rapidly in Europe, and it began to replace ether as an anesthetic. But surgeons quickly returned to the use of ether when chloroform was discovered to be highly toxic.

In popular culture, especially books and films, a pervasive image is that of a chloroform-soaked handkerchief held over the victim’s mouth, resulting in unconsciousness. In reality, more than just a few drops would be required to knock somebody out, or to result in death (Beaver readers, don’t try this at home. Remember, this was how John Wayne Gacy and Jeffrey Dahmer drugged their victims).

In the case of Dr. Cream, an empty bottle of the poison was found lying beside one of his victims. He would have been aware that a full dosage was necessary to achieve his malevolent aims.

Chloroform is found in today’s environment and traces can be found in automobile exhaust and sewage-treatment products. It is a by-product of chlorinated drinking water. It is also used in the manufacturing of pesticides and dyes.

Next time you find yourself with your head in the fridge gazing at leftovers from another era, recall that in this modern one, chloroform is mainly used in the production of Freon, a refrigerant.

Four More Ripper Suspects

The Lodger

One of the most popular images of Jack the Ripper is that of a quiet gentleman of some wealth who rents a room from a retired couple at a higher-than-market rate. Though quiet, he displays idiosyncratic habits, reading the Bible aloud during the day and going on nocturnal wanderings. The wife becomes suspicious, noticing that her lodger’s evening disappearances coincide with the murders.

M.J. Druitt

A prime suspect for many years, M.J. Druitt, a barrister, was pulled out of the Thames River in 1888. His possible suicide has been linked to guilt over the murders. But the handsome Druitt, who bore a striking resemblance to Prince Albert Victor (another suspect), had a penchant for young boys, and likely not Whitechapel women. There is little evidence to implicate him.

Severin Klosowski

Born in Poland in 1865, Severin Klosowski (a.k.a. George Chapman) came to England with a surgeon’s skills. In time, he was found guilty of murdering at least three women to whom he had romantic ties. He worked as a barber in the Whitechapel district and is the only suspect who is known to have been capable of serial murder. A strong case.

Prince Albert Victor

Born in 1864 to Edward, Prince of Wales, and Princess Alexandra, “Eddy” is thought to have suffered from syphilis and gone insane. In 1970, Dr. Thomas Stowell wrote an article that caused a stir, theorizing the Royal Family knew the prince was the Ripper and covered up his guilt. Still, Prince Albert Victor was not in London when most of the murders occurred.

Et Cetera

Jack the Ripper A to Z by Paul Begg, Martin Fido, and Keith Skinner. Headline Book Publishing, London, 1994.

Doctor Thomas Neill Cream (Mystery at McGill) by David Fennario. Talonbooks, Vancouver, 1993.

A Prescription For Murder: The Victorian Serial Killings of Dr. Thomas Neill Cream by Angus McLaren. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1993.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk necktie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. Made exclusively for Canada's History.