Roots: Your Place or Mine?

In my student days I roomed with an actor who practised elocution with the aid of a road map.

“Now loading on platform four,” he would intone in a voice reminiscent of a bus-terminal PA system, full of explosive consonants and vowels lengthened dramatically or eliminated altogether, “Straathroyyyyy, via Leam’ngt’n, Flesh’rt’n, Ferrrrg’s, aaand Peff’lawwww. Allll a-bud.” Then it was on to his next farcical itinerary.

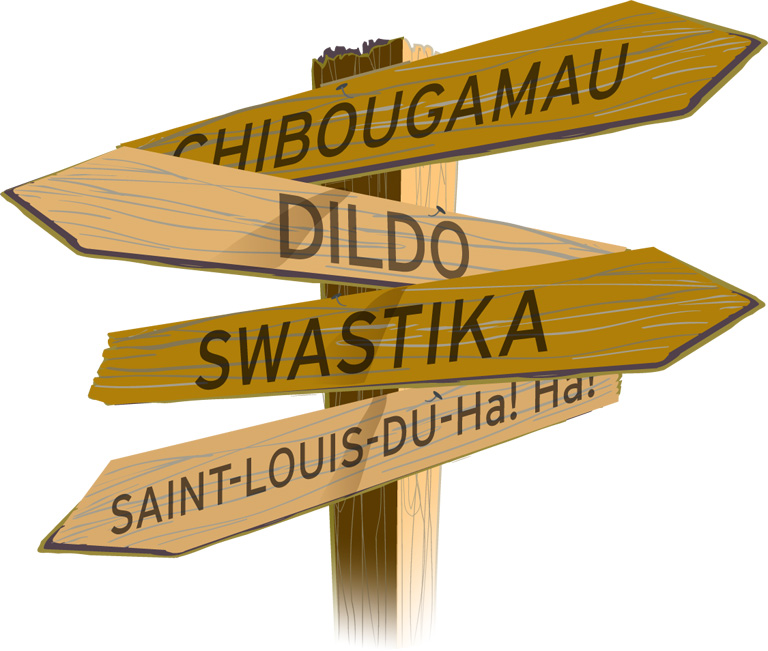

That’s when I first realized place names could be fun for adults. Why should it only be schoolkids who get to laugh out loud at names like Medicine Hat, Alberta, and Chibougamau and Saint-Louis-du-Ha! Ha!, in Quebec?

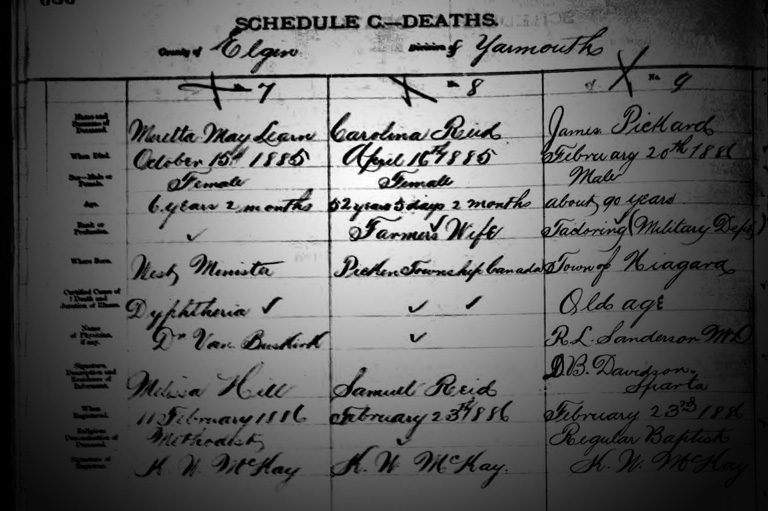

Almost fifty years later, place names once again feature in my life. As a responsible genealogist, I’m acutely aware that pinning down the location of an ancestor is essential to the identification of the correct person and the study of the appropriate records. Research rigour demands that we take these things seriously.

Certainly our forebears did. At least until Elizabethan times, local history and geography studies were solemnly and inextricably linked in what is now known as “the chorographic tradition.” To William of Malmesbury, writing in the twelth century, the depiction of the land and the tales of its inhabitants were inseparable. William Camden’s county-by-county Britannia, published in Latin in 1586 and English in 1610, was reprinted, reissued, and gravely repurposed for the next quarter of a millennium. Everyone understood that this was capital-S-serious subject matter.

The scholarly study of place names took hold in the nineteenth century. The biggest challenge was to identify and clarify the folk etymologies that had cheerfully and haphazardly modified European place names over many centuries, even millennia.

For example, the English town of York had been known by broadly similar-sounding names in several different languages (Celtic, Latin, Anglian, Old Norse, and every era of English) with shifting meanings to accommodate each successive tongue.

In North America we do not have these accretions of language to the same degree. Sometimes we’re not entirely sure what a word meant in a First Nations tongue, such as Chibougamau. And there are conflicting legends as to how a place originally got its First Nations name, as in Medicine Hat (a literal translation into English). Usually, though, we have at most one layer of linguistic confusion to deal with, not the four or five that are possible in the Old World.

In fact, many Canadian place names are rather easily traced to a specific source, especially honorifics that celebrate royalty, aristocracy, saints, soldiers, politicians, or community founders. Among the less exalted ranks, pioneer farmers, railway officials, Matthew Yathon and postmasters often lent their names to their communities.

These days, the naming of places is a bureaucratic business.

The Geographical Names Board of Canada oversees approximately 350,000 official place names, and the board and its provincial counterparts require exceptional circumstances before commemorating a person. So don’t get your hopes up if you’re not a monarch, a prime minister, or Rick Hansen. Descriptive names, perhaps Aboriginal in origin, will do nicely.

If you need to identify a Canadian place, Natural Resources Canada operates the Canadian Geographical Names Data Base with an online query tool that “provides many ways to search for a current or former official name.” Prospective merriment is not one of the search criteria.

No discussion of Canadian place names would be complete without mention of Alan Rayburn, the doyen of his field, author of the book Place Names of Canada, and contributor of the article “Place Names” to the Canadian Encyclopedia. Few could match his erudition in authoritatively describing the chaste origins of the placename Dildo, in Newfoundland and Labrador, while maintaining the prose equivalent of a poker face.

From Rayburn we learn that many places almost adopted different identities.

Regina, for example, might well have been Wascana or even Pile of Bones. Would schoolchildren around the world know Medicine Hat today had it become Smithville instead? And would the recreational allure of Kenora, Ontario, be quite as appealing to sporty types if it had continued with the moniker Rat Portage?

Then there are the Ontario communities once known as Berlin, Stalin township, and Swastika, but today called Kitchener, Hansen township, and — really? Are you sure? Still Swastika? Oh, my.

I don’t suppose Swastika’s residents were less passionately anti-Nazi than other Canadians. Yet they couldn’t see why they should cede their forefathers’ benign heritage to a vanquished, Johnny-come-lately evil. Don’t hit people where they live. Even the oddest of names may be no joking matter.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!