Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Laurier’s Sunny Ways

Wilfrid Laurier loved to read. As a boy in mid-nineteenth century Quebec, he was familiar with morality tales told by the ancient Greek slave and storyteller Aesop. In one of Aesop’s fables, the sun and the wind hold a contest of strength; the sun, with its warm and kindly approach, wins. From this fable Laurier articulated his approach to politics—the sunny ways of gentle persuasion, conciliation, compromise.

Fast-forward to the present. Sunny ways are again in vogue—although often misunderstood to mean unbridled optimism. Laurier, whose pensive face stares out at us from the five-dollar bill, may have sounded overly confident when he declared that “the twentieth century belongs to Canada,” but he was no fool.

As a French Canadian, he saw that Confederation could overwhelm the rights of the francophone minority and he initially opposed it. But once Confederation took place, he did his best to hold the country together. Although he doubted English Canadians would elect a French Canadian to lead them, they did. He held office for fifteen years, the longest unbroken stretch of any prime minister.

Tremendously popular in his time, Laurier continues to be respected today. Historians rank Laurier among the top three of Canada’s prime ministers—the others being John A. Macdonald and William Lyon Mackenzie King.

November 20 of this year marks 175 years since his birth, so it’s timely to look back at Laurier and what his legacy means to us today. In this article, we interview Réal Bélanger, a biographical historian of Laurier and the co-director of the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Senator André Pratte, the former editor-in-chief of La Presse, and Roy MacSkimming, author of the novel Laurier in Love. Each offers a unique perspective on a complex man whose words from more than a century ago continue to ring true today.

Story continues below.

Photo Gallery

-

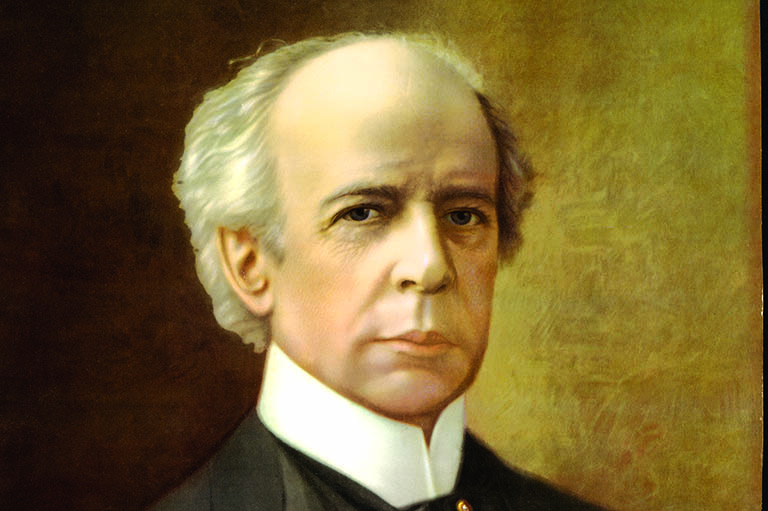

Sir Wilfrid Laurier, artist and date unknown.Library and Archives Canada / Acc. No. R1300-198

Sir Wilfrid Laurier, artist and date unknown.Library and Archives Canada / Acc. No. R1300-198 -

Assemblee des six-comtes, by artist Charles Alexander Smith, depicts Patriote leader Louis-Joseph Papineau speaking in 1837 during the Rebellion of Lower Canada.Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec

Assemblee des six-comtes, by artist Charles Alexander Smith, depicts Patriote leader Louis-Joseph Papineau speaking in 1837 during the Rebellion of Lower Canada.Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec -

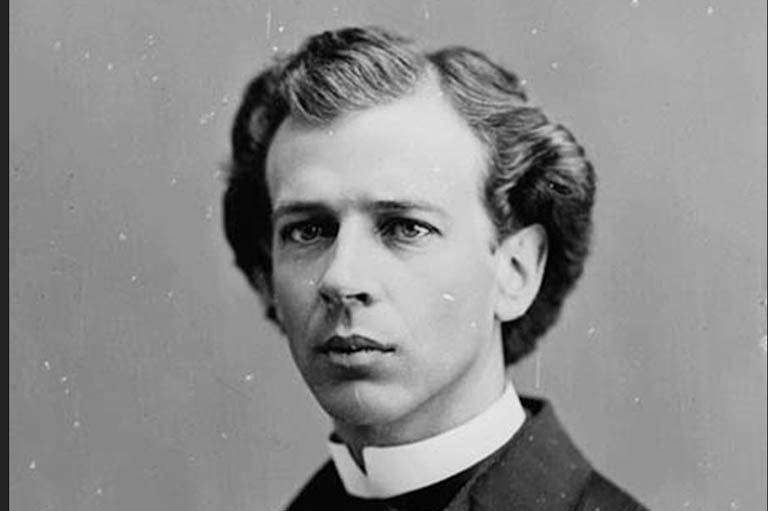

Wilfrid Laurier in 1874, the year he first won election to the House of Commons as a Liberal MP.William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-026430

Wilfrid Laurier in 1874, the year he first won election to the House of Commons as a Liberal MP.William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-026430 -

Zoé Lafontaine, Laurier’s devoted wife, in 1878.William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-026528

Zoé Lafontaine, Laurier’s devoted wife, in 1878.William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-026528 -

Émilie Lavergne, Laurier’s close friend and possible mistress, circa 1897.William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-196357

Émilie Lavergne, Laurier’s close friend and possible mistress, circa 1897.William James Topley / Library and Archives Canada / PA-196357 -

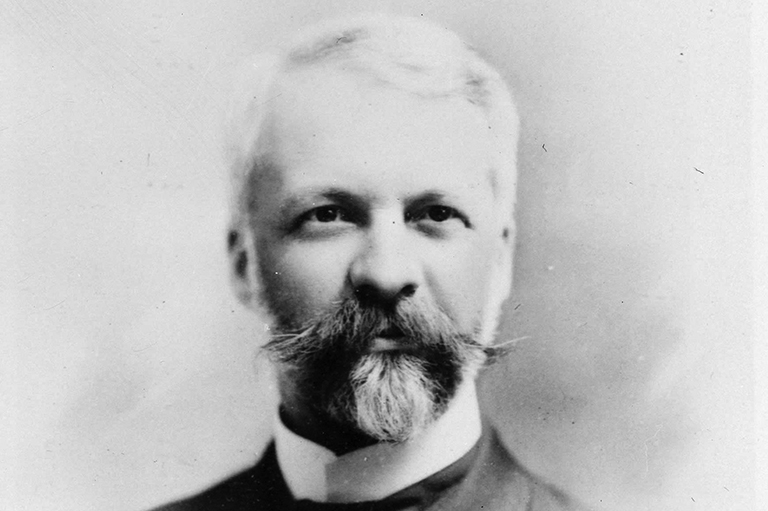

Armand Lavergne, Émilie Lavergne’s son, who many contemporaries thought bore a striking resemblance to Wilfrid Laurier. As a Quebec nationalist, he would grow up to become a thorn in Laurier’s side.Armand Renaud Lavergne / Library and Archives Canada / PA-135125

Armand Lavergne, Émilie Lavergne’s son, who many contemporaries thought bore a striking resemblance to Wilfrid Laurier. As a Quebec nationalist, he would grow up to become a thorn in Laurier’s side.Armand Renaud Lavergne / Library and Archives Canada / PA-135125 -

Firebrand Liberal MP Henri Bourassa was often at odds with Laurier.Library and Archives Canada / C-009092

Firebrand Liberal MP Henri Bourassa was often at odds with Laurier.Library and Archives Canada / C-009092 -

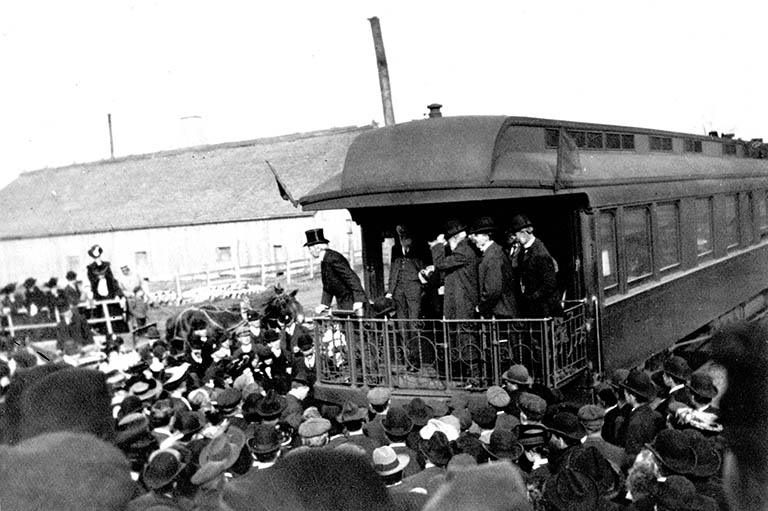

Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier gives a speech during the 1904 election campaign from a railway car in Exeter, Ontario.Library and Archives Canada

Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier gives a speech during the 1904 election campaign from a railway car in Exeter, Ontario.Library and Archives Canada -

Sir Wilfrid and Lady Zoe Laurier go to a Parliamentary luncheon at the 1907 Colonial Conference in London.Library and Archives Canada / C-033388

Sir Wilfrid and Lady Zoe Laurier go to a Parliamentary luncheon at the 1907 Colonial Conference in London.Library and Archives Canada / C-033388 -

Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier campaigns for re-election in 1908. At age sixty-seven, Laurier was returned to office for his fourth consecutive term with a majority government.Library and Archives Canada / C-00932

Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier campaigns for re-election in 1908. At age sixty-seven, Laurier was returned to office for his fourth consecutive term with a majority government.Library and Archives Canada / C-00932

What influenced Wilfrid Laurier in his early life?

Réal Bélanger: The first influence was his family. Laurier’s father was a surveyor with a vision. He was mayor of his municipality and was very active in politics, particularly the politics of the Rouges—as the Liberals were then called in Quebec. His mother was passionate about literature, art, and nature, and she left an impression that stayed with Laurier all his life.

During his student years, there were his professors and friends. In 1852, he went to school in the town of New Glasgow, about ten kilometres from his home in Saint-Lin, where he came into contact with anglophones. After that he attended Collège de l’Assomption, which at the time was strongly ultramontanist [promoting the authority of the Church in civil matters]—a movement and a vision which Laurier did not like but which would preoccupy him throughout his life. Then he discovered the Institut canadien and the Rouges in Montreal. These were all influences that would have a significant impact throughout his life.

Roy MacSkimming: Laurier was of the ninth generation of a family that traced its Canadian roots to 1642. Canada was in his blood—a French Canada, of course—but he also learned to live with the difficult reality that his ancestral home was now part of the British Empire. As a boy in New Glasgow he read Shakespeare, Milton, and Burns and spoke English fluently with a Scots inflection.

His strongest female influences were his mother, Marcelle—she named him Wilfrid after the hero of Walter Scott’s novel, Ivanhoe—and his stepmother Adeline, who loved him as her own. Laurier would always be comfortably at home in the company of women.

Senator André Pratte: When he was very young his father sent him to board with two English-speaking families that he knew. One was Protestant, the other was Catholic. So he had an experience very few young Quebeckers living in rural areas had.

He came to see Protestants as ordinary people whose faith was not an obstacle to being good, generous people. At that time it was extremely important, because the Catholic Church was very powerful and being a Protestant, in the view of the Catholic Church, was very bad.

How would you describe his personality?

Bélanger: Laurier had a fairly complex personality. He was a man of distinction but also a simple man. He was extremely charming and courteous, traits that were fairly uncommon in his time. He was open, honest, at times courageous and determined, and he was unflinchingly loyal to his friends.

But he was also a dreamer. He was inclined to contemplation, preferring reading to sports. He was a romantic who could be captivated by a beautiful landscape. He was also a generous humanist who believed strongly in tolerance and freedom. He was a pragmatist who favoured compromise and disliked one-sided outcomes.

He was not always a hero. According to some, he was without feelings, without strong convictions on any subject. To others he was a man who always wore a mask, always played a game. To them, his smiles, like his sorrows, were calculated.

So he was somewhat of a contradiction. In fact, Laurier was a man of many parts.

MacSkimming: All his life Laurier was a paradox: a mixture of self-doubt and self-confidence, idealism and realism, romantic French sensibility and steely English resolve. Above all he was highly charismatic. His sunny ways won the peoples hearts, but once accustomed to power he wielded it like a sword to achieve his goals.

Pratte: One thing that is certain is that he was a very kind man. Even his political enemies had a hard time disliking him. In his speeches and in his correspondence with people who were very critical of him, he is always very polite. We tend today to think that negativity in political campaigns is unique to today’s politics. But politics in Laurier’s time was quite tough and accusations flew. However, Laurier was quite different. He was critical of his adversaries’ arguments, but he was not critical of them as people.

As he got older, he developed a noble presence, so that people felt at once close to him. Yet at the same time he held himself at a respectful distance. He was not the kind of politician who would slap people on the back and say, “Hey, how are you.” Nor was he arrogant. He was a gentleman, really.

The Catholic Church tried to stop him from winning back his seat in an 1877 byelection. What happened and why?

Bélanger: Because the Conservatives and the Church didn’t like Laurier and Liberals of all kinds, they did everything they could to make sure he was defeated in the Drummond-Arthabaska byelection. There were heated head-to-head debates with crowds turning to violence and one man even being killed.

During the campaign, Laurier was portrayed as someone who had never bothered to have his children baptized, despite the fact he had no children. He was said to be a Protestant minister in favour of priests marrying. It was even said that Laurier brought the guillotine to Canada so that French Canadians could wade in the blood of priests!

Another tactic used was corruption. Louis-Adélard Senécal [a businessman] was instrumental in buying a significant number of votes. So naturally Laurier lost. But Laurier later ran in a different riding, this time in Quebec East. And this time he won.

Pratte: Laurier was treated like any other liberal because the Church feared liberals. Whether they were moderate or radical, all liberals were perceived by the Church as dangerous. They saw them as being like liberals in France, where they were seen as being behind revolutions. So the priests in the local churches would tell their parishioners not to vote for the Liberal Party candidate. If you did, you would commit a mortal sin and you would go to hell. For many French Canadians at the time, who had little education, it was a threat they took very seriously.

At first, Laurier was not in favour of Confederation. Why? And what made him change his mind?

Bélanger: In fact, from 1864 onward and until Confederation, on July 1st 1867, Laurier adopted the main arguments of the Parti Rouge, which were very much against Confederation. His opposing views were expressed in speeches in Montreal and in newspaper articles, the most noteworthy being in le Défricheur—Laurier was even at one point that newspaper’s editor. Laurier argued that Confederation would be the death of French Canada, since it would be detrimental to its interests and its autonomy—it would be swallowed up by the English Canadian majority And he was opposed to the fact that the French Canadian people were not consulted. Moreover, he deemed it important—and this is often overlooked—that French Canada demand and obtain a free and separate government. So this was the position taken by the man who some thirty years later would lead the country whose creation he was now trying so hard to prevent.

Laurier changed his mind after Confederation took place. He was simply following his party’s decision. Parti Rouge leader Antoine-Aimé Dorion accepted what was essentially a done deal and decided to work within the Confederation in order to lessen the damage and the pain felt by French Canadians under this new administration. Laurier did the same. He always takes things as they are and so he accepts Confederation for what it is.

Laurier is seen as one of Canada’s greatest political orators. Which of his speeches or statements stand out for you?

Bélanger: It depends on what you mean by the greatest. I would say the first really important one for him was his speech of June 26, 1877, in Quebec City on liberalism. By setting out a concept of moderate liberalism, as opposed to the radical liberalism he had previously supported, he became an important figure on the national stage. And his concept of liberalism gave his party a welcome boost.

The second, I would say, was a speech he gave in the House of Commons, on March 16, 1886, on the question of [francophone Metis leader] Louis Riel and his recent execution. “We cannot make a nation of this new country by shedding blood,” he asserted, “but by extending mercy and charity for all political offences.” Basically, Laurier proposed that Canada could build a solid foundation and rally the two founding peoples, as they were called at the time, through charity and tolerance.

The other speech that I think was very important was the one he gave on May 10, 1916, in the House of Commons, following the Ontario government’s adoption of Regulation 17, which limited the use of French as the language of instruction and communication to the first two years of elementary school. Laurier eloquently pleaded the cause of citizens of French descent in Ontario.

MacSkimming: Among his statements, I find this one from 1911 absolutely compelling: “I am branded in Quebec as a traitor to the French, and in Ontario as a traitor to the English. In Quebec I am branded as a jingoist, and in Ontario as a separatist. In Quebec I am attacked as an imperialist, and in Ontario as an anti-imperialist. I am neither. I am a Canadian. Canada has been the inspiration of my life.”

And I was also struck by this 1894 quotation—contemporary readers may notice a similarity to the last public statement by the late New Democratic Party header Jack Fayton: “And in all the difficulties, all the pains, and all the vicissitudes of our situation, let us always remember that love is better than hatred, and faith better than doubt, and let hope in our future destinies be the pillar of fire to guide us.”

Pratte: In his speech of June 26, 1877, Laurier uses his deep knowledge of European history to show why Canadian and Quebec Liberals are different, and how their models are British models of liberalism. This is very clever, because the Church is very loyal to the British Crown and appreciates the stability that the Crown provides.

He also tells the Church, we don’t mind if you meddle in politics, but what you cannot do is impose your will on people because, if you do so, you will provoke what you fear the most—revolution.

It’s a brilliant strategy. It will not convince the Church, of course, but it will convince Liberals themselves that they have in Laurier a new leader, and it will be the beginning of a pivot from Rouge radicalism to more moderate liberalism.

Laurier was often reluctant to take on leadership. Why?

Bélanger: Essentially for four reasons: Leadership wasn’t to his liking, his health was poor, he wasn’t wealthy, and he didn’t believe that a French Canadian could lead a national party.

MacSkimming: He anguished over going deeply into debt, since party leaders were inadequately paid and were expected to cover many political expenses—such as dinner parties for important guests—out of their own pockets. He would certainly have been better off financially had he just remained a lawyer in Arthabaska. To help him out, the Liberal Party purchased an Ottawa home for the Lauriers, now a National Historic Site, where Laurier’s successor Mackenzie King later lived.

Pratte: Even after he had agreed to accept the leadership, you can find many letters where he said I’m going to quit and go back home to Arthabaska, to live the quiet life of a simple lawyer. So it’s quite paradoxical that he stayed on so long. I can never make out if that reluctance was sincere or not.

His reluctance may sometimes have been a strategy. During one crisis in his government, he wrote a letter of resignation, knowing full well everyone would rally around him because there was no successor. So he could use his threat of resignation as a tool, as a strategy to rally people around him.

What are your thoughts on Laurier’s love life?

Bélanger: Laurier’s love life was really quite complicated and really heated up around 1896-97 to 1900. He had married Zoé Lafontaine in 1868, whom he had met in Montreal. But around 1874, he met Émilie Barthe, who became the wife of his associate Joseph Lavergne. Although Zoé was a good wife for Laurier, she didn’t have—how would I put it?—the stature of Émilie. Like Laurier, Émilie loved literature, was very cultured, and travelled in elite social circles. So this woman captivated Laurier, and he fell in love with her. I think the letters he wrote her attest to his love.

Even though this love was strong, and in spite of the rumours—one of the rumours was that Armand Lavergne, the son of Émilie and Joseph Lavergne, was actually Laurier’s son—I believe the relationship remained platonic.

Generally these rumours didn’t harm Laurier’s career, until he became prime minister in 1896. That same year, Laurier appointed Joseph Lavergne judge for the Ottawa district, which meant that Émilie came to live in the Ottawa area. She attended all the soirees, she had considerable presence, she was a remarkable hostess, and Laurier saw a lot of her. So people began whispering, and the rumours got stronger, to the point that Laurier realized he had to do something. Laurier sort of broke off the relationship around 1900-1901, when it looked like it could become a hindrance in Ottawa.

MacSkimming: Before he became prime minister, when he was in Arthabaska practising law, there was a ritual, usually in the afternoon, when he would rise from his desk and say to his law partner, Joseph Lavergne, “Joseph, if you will permit me, I will go and visit your wife,” and Joseph would never refuse permission. So Laurier would tuck a book under his arm and walk four doors down the street to the Lavergnes’ house, where he and Émilie would sit and commune over the latest book they were reading together.

Ostensibly it was a friendship based on a mutual love of books and ideas. There is no definitive proof that it was consummated, yet Lauder’s letters to Émilie are filled with passionate romantic longing and an intense interest in her two children. Many observers noticed the resemblance between Laurier and her son, Armand Lavergne, who grew up to be a Quebec nationalist and a thorn in Laurier’s side.

The affair was condoned by Zoé Laurier and Émilie’s husband and became generally accepted in society, even after Laurier was prime minister. Zoé and Émilie were actually friends. They would go places together and do things together. Laurier finally ended the affair when Émilie, seeing herself as the power behind the throne, became overly demanding.

There was one incident in which Émilie insulted the guest of honour, a young Winston Churchill [who was on a North American speaking tour as a hero of the Boer War], at a Rideau Hall soiree. Émilie was quite a Quebec nationalist, very outspoken, and questioned Churchill about British motives in South Africa. [The incident was obliquely described in a January 1901 column in Saturday Night by Ottawa social columnist Agnes Scott.] Churchill was apparently very offended by her criticism of British actions. I think we can conclude that Laurier was quite angry at Émilie for antagonizing an important visitor.

In any case, we know it’s true that shortly after this Laurier effectively banished Émilie from Ottawa by appointing her husband to the bench in Montreal.

Pratte: There were rumours, but they did not affect his extraordinary reputation. After he became prime minister, he took the letters Émilie had sent to him and mailed them back to her, which seems to indicate he felt some embarrassment at having those letters. We know he had a very long marriage with Zoé. They had no children, and they were very close until the end of his life.

He suffered from ill health for much of his life. How did that affect his career in politics?

Bélanger: He always feared tuberculosis, which had killed his mother. And for a long time he thought he himself was dying of tuberculosis. He frequendy coughed up blood before he moved to the Bois-Franc region in 1866—67. In the early 1900s, he even feared he had cancer. So his health problems definitely slowed him down, made him hesitate to pursue his career, and to assume the leadership of his party. He often had to take it easy, had to limit his activities, take breaks, even take vacations, which wasn’t a standard custom in those days. At times, he even considered ending his career. But his passion for politics was so strong that, in the long run, despite the worry, he always forged on.

MacSkimming: Laurier was a bit of a hypochondriac. Though he naturally feared the tuberculosis that had killed his mother and sister, he initially used it as a reason not to marry Zoé, until a doctor disabused him of his belief that he carried the disease. He continued to be troubled by a bronchial cough but was nonetheless able to meet the physical demands of office. The devoted Zoé watched over his health and diet, insisting he travel with his own clean bed linens. Laurier lived to the ripe old—for the times—age of seventy-seven, dying in harness after an astonishing thirty-two years as Liberal leader, fifteen of them as prime minister.

What was Laurier’s attitude towards the rights of Indigenous peoples?

Bélanger: It can’t be said that Laurier’s position on Indigenous people differed greatly in substance from that of John A. Macdonald’s Conservatives. This is clear from a speech he gave to the House of Commons on April 20, 1886. While he said he was sympathetic to Aboriginal claims, deep down he shared the view of many others regarding the need to “civilize” Canada’s Aboriginal Peoples, whom he called “savages,” as did everyone in those days. The prevailing notion was to civilize them by, for example, placing children in residential schools so they could be assimilated into white culture.

I’ll conclude by adding that, in 1899, Laurier’s government signed Treaty 8, one of the end results of which was that the Indigenous people relinquished title to much of what are now northerly portions of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia as well as a southerly portion of the Northwest Territories.

Pratte: Laurier was liberal in his thinking but not immune to the prejudices of his day on many topics, whether it was about the rights of Indigenous people, the right to vote for women, or the rights of immigrants, for instance.

What were some of the biggest challenges that Laurier faced as prime minister?

Bélanger: His biggest challenges are reflected in his objectives when he came to power. At the outset, it was to reinvigorate the country, which had been hard hit by the economic depression a few years earlier and by the fierce cultural and religious animosities between French-Canadian Catholics and English-Canadian Protestants. As a result, Laurier also had to rebuild national unity, which had also suffered greatly.

Another of his objectives was to change the nations mood, to get rid of the bitterness Canadians were feeling. He wanted to give people hope. So when he came to power he wanted to expand the country’s development opportunities and undertake large-scale projects. He wanted to make sure the twentieth century became, as he put it, Canada’s century. So his goal was tangible development.

Another challenge for him was to develop the West through immigration, and in so doing to create new provinces. He wanted to reconsider the relationship between Canada and the English motherland as well as the relationship with the United States. He wanted to bring Quebec solidly into the fold of the Liberal Party and to make the Liberal Party open, biracial, and much more pragmatic. Those were the challenges he took on when he came to power, and he accomplished several of them.

Pratte: His greatest challenge and his greatest legacy were the same. When we talk of the sunny ways of Laurier, it’s about his approach to convincing the different groups that compose Canada to work together. He did not try to impose the solution of the majority—or the minority. He tried to get people to work together by rational argument. That’s the sunny way, right? But that way of doing things was always challenged by events, or by the majority, or by extreme groups.

It was extremely difficult for him to hold on to this approach and make it work. When he lost the 1911 election, he may have thought his sunny ways were not working, that prejudice was winning. It was a huge challenge.

Laurier was always looking for compromise. Is there anything on which he didn’t compromise?

Bélanger: I think one area in which he would never have agreed to compromise is the way in which he led his government. He was truly the master of his administration.

Pratte: You know, Henri Bourassa [a Quebec nationalist who often clashed with Laurier] said something like that if Laurier were to arrive in hell, he would attempt compromise with the devil. It’s not far from the truth. There’s not much Laurier would not compromise on, except the unity of the country. Sometimes his compromise went too far, at least when it came to the French minority.

What do you think was his biggest mistake?

Bélanger: A political statesman of his stature has many success stories but he will also make mistakes. Among Laurier’s mistakes there is one that had major repercussions for Canada’s cultural evolution. It was when Alberta and Saskatchewan were being created in 1905. In keeping with the Constitution, Laurier wanted these new provinces to have separate schools, denominational schools, to ensure the survival of the country’s bicultural dimension in these provinces. But the English-Canadian Protestant majority and its ministers refused Laurier’s proposal. So Laurier had to concede and return to the status quo that previously existed in these territories.

In my opinion, that was a big mistake. He should have stood up to the objectors and waged the battle of his political career. This was probably the country’s last chance of finding the means to become a truly bicultural nation.

Laurier never had a chance to retire and rest on his laurels. What made the last years of his life difficult?

Bélanger: Laurier lost power on September 21, 1911, and became leader of the Opposition until his death in 1919. So Laurier still had lots of work to do after his defeat. First he had to oversee the rebuilding of his party. That was successful until 1917, and that was important. Then he had to deliver a strong and credible opposition in the House; that was successful. He also wanted to ensure that his work would not be undone by the new prime minister, Robert Laird Borden. In this, he was partly successful.

During the First World War, Laurier’s intent was ensuring that Canada did its duty, so he contributed to many recruitment efforts for the war. He also wanted to prevent negative fallout from the war and conscription. That was a failure.

His party was left quite divided, with several of its most prominent members, its MPs, joining Borden’s Union [coalition] government. And there is no denying that the country was left divided. So at the end of his political life, the overall goals of his career—which were to build a solid and united biracial party and to build national unity—those two goals were shattered.

Pratte: After the war was over, he reached out to Liberals in English Canada and called for a rebuilding of the party. He was by then pretty old, he had been leader of the party for thirty years, and he was still interested in building the party and forgetting the conflicts of the past. I find that quite impressive and quite moving.

What do you think is Laurier’s greatest legacy to Canada?

Bélanger: I believe his greatest legacy is to have shown Canadians that compromise and conciliation are the best ways to govern, to build, and to consolidate this country, a country made up of so many different and opposing elements. But his career also showed that if compromises too often satisfy only the majority, in the end they will fail.

MacSkimming: Laurier’s great legacy was twofold. The first is recognition of French Canadians as equal founding partners in the nation. His other legacy was advancing Canada along the road to full nationhood. Laurier’s assertion of Canada’s autonomy at imperial conferences and his creation of a Department of External Affairs were important steps toward that goal.

Pratte: Foreign affairs was where he had great success in breeding a new sense of Canadian nationalism. But to me his “sunny ways” was his greatest legacy, and it’s as pertinent today as it was then. I just hope that the fact it’s used today by one politician of one political party does not taint it by a partisan perspective, because to me sunny ways do not belong to one particular party. The sunny way is the only way to maintain Canada as a united project of a diverse group of people.

Otherwise, there’s no concrete policy you can put his name beside. You can’t say he was a great railway man or free trader. His policy was uniting Canada, and the rest was accessory to that.

How does Laurier compare to politicians today?

Pratte: Someone like American President Barack Obama reminds me of Laurier, in a way. He’s certainly the same kind of public speaker Laurier was, and there’s a kind of naïveté in Obama that you could find in Laurier also. I think Laurier’s great legacy was his approach to politics, not concrete achievements. And maybe the same can be said of Obama.

And, of course, both came from minority populations.

Pratte: Absolutely. If Laurier had not been prime minister, who knows, maybe no French Canadian would have been prime minister. Maybe French Canadians would have felt so estranged from the rest of Canada that they would have chosen to go their separate way long before the separatist movement of the 1960s. Who knows?

The Rise of Laurier

1871 Wilfrid Laurier begins his political career as a member of the legislative assembly of Quebec. He represents his home riding of Drummond-Arthabaska.

1874 Laurier is elected to the House of Commons, where his eloquence first comes to attention. He is appointed minister of inland revenue in 1877.

1896 He becomes Canada’s first French-Canadian prime minister, a position he will hold for fifteen years, the longest unbroken mandate in Canadian history.

1897 Laurier represents Canada at Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee and receives a knighthood. He also resists Britain’s call for an imperial federation.

1899 English and French Canada are split over participation in the Boer War. Laurier compromises by sending a volunteer force to South Africa.

1903 Laurier begins construction of the new National Transcontinental Railway (NTR), a popular move at the time but it will lead to huge cost overruns.

1905 Laurier creates the new provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta, but his bid to ensure separate schools for their francophone minorities fails.

1910 Pressured to help finance Britain’s navy, Laurier compromises by creating a Canadian navy that can be placed under British command in times of war.

1911 Laurier loses the federal election to Conservative leader Robert Borden. The loss comes after Laurier’s push for freer trade with the U.S. backfired.

1917 While supportive of the war effort, Laurier’s stand against conscription splits his party and leads to the election of Borden’s coalition Union government.

1919 Opposition Leader Sir Wilfrid Laurier has a stroke and dies on February 17 at the age of seventy-seven. About 100,000 people attend his funeral.