Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

History in the Making

“I’m going to try to keep you entertained on a Friday afternoon,” says Kathryn Whitfield, OCT, smiling at her Grade 10 history students at Northview Heights Secondary School, where she also teaches French, drama and equity studies. “How many of you watch Murdoch Mysteries?”

About a third raise their hands for the CBC detective who unravels turn-of-the-century murders. “How does he solve a crime?” Whitfield asks. They reply, “He talks to people. Looks for clues. Does research. Gets second opinions.” “That’s right — that’s fieldwork,” replies the high school teacher. “He puts all the evidence together to come up with a conclusion. Fieldwork in history involves analyzing and interpreting historical objects to piece together a story. Today, we’re going to start by looking at historical photographs.”

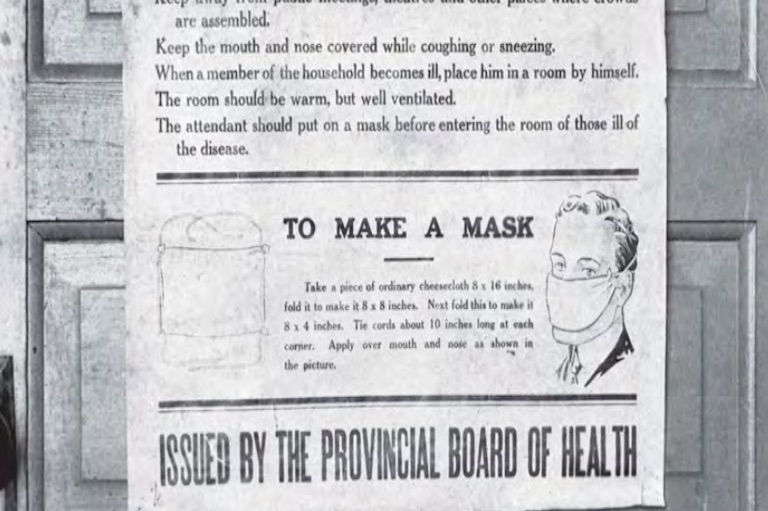

Whitfield projects a black-and-white image on her Smart Board screen and asks, “What’s the first thing you notice?” The teens volley back their answers: a young girl, scraps of broken wood, is that a garage? “What is her social class?” “She’s in a dirty alleyway. The garage looks rundown. She’s poor,” they reply.

They discuss why the photographer stood so far away to shoot the girl. Whitfield explains it was to capture the background — she’s standing in the shadow of Old City Hall, steps from today’s Eaton Centre shopping mall. “The caption on the bottom of the photo reads ‘Department of Health, number 187, May 1913.’ Why would the Department of Health be taking photos?” Whitfield asks. “It doesn’t look like a healthy place to live,” a boy says. “It looks like someone tried to make a shelter but it collapsed.”

Eventually, Whitfield fills in the rest of the girl’s story for the Grade 10s. She lived in St. John’s Ward, the gateway to Toronto for thousands of new immigrants dating as far back as the mid-1800s. Bordered by College, Queen and Yonge streets, and University Ave., it was the worst of the city’s urban slums.

Landlords built shacks and outhouses to take advantage of the demand for cheap housing, while the health department documented filthy rooming houses, water-borne illness and the stench of waste. But instead of addressing the unsanitary conditions, the city cleaned up the area by razing it. The immigrants were forced to relocate, while churches, synagogues, theatres, a school and other landmarks were torn down.

Today, Nathan Phillips Square and Toronto City Hall stretch over the soil where this girl once lived in a garage with 10 people. The history teacher pauses to let this information sink in. “Does any of this bother you?” she asks, her resonant voice suddenly softened. “Yes,” someone says quietly. “It bothers me too,” Whitfield says.

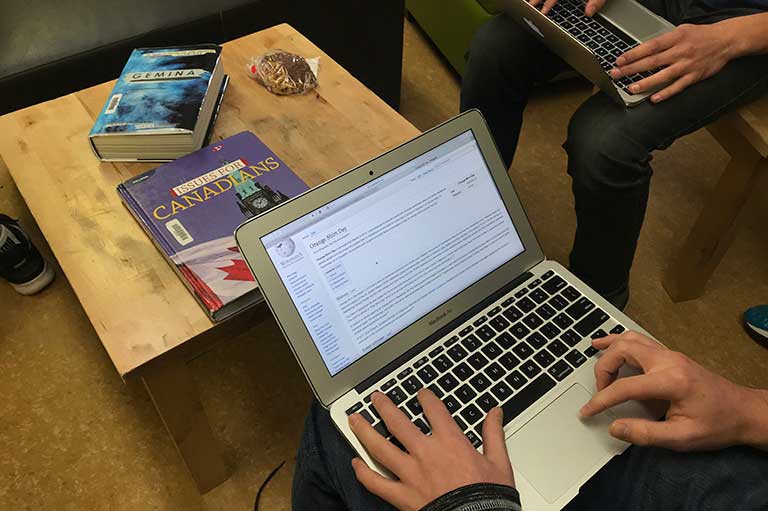

Whitfield is laying the groundwork for a unit that will take her class on a journey to the heart of their city and back in time. Instead of leaning on textbooks, they explore, do fieldwork, analyze data and make their own observations about the past. By giving them the tools and freedom to do history — the same way young scientists do experiments — Whitfield is winning fans among teens and judging panels.

She won a 2012 Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Medal for inspiring Canadian youth to build a better world, and created a unit about the Ward that earned her a 2015 Governor General’s History Award for Excellence in Teaching.

“The challenge for teachers of compulsory courses like history — where the content itself potentially isn’t going to have much flair — is how to get the students engaged,” says Peter Paputsis, OCT, principal of Northview Heights, in the Toronto District School Board. “Katy never stops at just delivering the material. She’s got this drive to go above and beyond. She engages students with real-life historical research and authentic learning experiences.”

It was the influence of Whitfield’s family that led her toward teaching history — her aunt worked as a historian for Parks Canada at the Citadel in Halifax, her mom was a teacher, and her grandparents and dad animated the supper table with their life stories when she was growing up.

Whitfield was the kind of child who clipped news articles when the space shuttle crashed, as well as other events that would one day appear in history books. During her university years, while working as an educational tour guide, she saw how much the younger generation enjoyed learning when given the opportunity to explore the real world. “Every time we walked past a landmark,” Whitfield recalls, “the kids would get so excited. ‘What are you going to tell us next?’”

In the meantime, the 14-year teaching veteran has collected countless life lessons from her own travels (including humanitarian trips to Kenya and Ecuador), and from standing on historic soil on five continents (from European battlegrounds to Cambodia’s Killing Fields). “I try to bring the world into the classroom — and to connect students with their communities,” Whitfield says. “That, to me, is authentic learning.”

She was inspired to dream up her two-week fieldwork unit after seeing a photography exhibit about the Ward at the Toronto Archives. Whitfield started by familiarizing her budding historians with primary source documents. One of her in-class activity stations featured archival photos, which they learned to decode by looking for clues and asking questions.

It’s one thing to read “squalor”; it’s another to see images of eight men living in one room or young children looking after each other. At another station, she introduced them to Goad’s Fire Insurance maps, dating back to 1884. Designed to guide firefighters to emergencies, these Victorian-era maps marked every road, landmark and laneway. Buildings shaded yellow were constructed of wood, while brick was in pink (pink indicated get there fast, yellow meant faster). The pupils then reviewed census data to learn people’s names, addresses, occupations, whether they owned or rented, plus the number of people living at a given address.

“Canadian history textbooks have their own slant,” Whitfield explains. “Primary source documents provide raw data so students can do their own critical thinking and analysis.”

Whitfield uses historical-thinking and inquiry concepts [see italics] — incorporated in the Ontario social studies curriculum in 2013 — to promote deeper thinking about historical documents. Cross-referencing primary source evidence allows them to understand how land was used, how the area evolved over time, and how to draw conclusions about patterns of continuity and change regarding immigration and settlement. They talk about cause and consequence and the ethical dimension of history in the context of building Toronto General Hospital from 1911 to 1913, which destroyed 356 buildings in the disease-ridden Ward.

If, for instance, the city hadn’t pushed out the Jews (by overcrowding and its decision to not improve infrastructure), we wouldn’t have the iconic Kensington Market — where they settled. An inquiry-based approach made history more interesting for former student Rojin, who took the course last year.

“We were able to connect with the people we were reading about, as though we were experiencing historic events as they happened,” she says. “We learned the significance of each event, which I believe is the point of history.”

Next, comes the kind of fieldwork done by real historians. They spend an afternoon on site walking through the former Ward while completing four “historical thinking missions” detailed in a booklet prepared by Whitfield. One task asks them to use historical maps to locate the spot where the photo of the girl was taken, then record field notes to describe, for instance, the current land use, space and buildings.

Other questions require them to identify evidence of continuity and change since 1912, at a particular intersection and a specific address. Finally, Whitfield asks everyone to stand in Nathan Phillips Square and imagine what they would see, hear, smell, feel and think if they were standing in the middle of the slum versus today.

“Doing fieldwork is like being a detective,” says Whitfield. “Every time you find something, you have to record it and make sense of it. It’s hard work, but in the end I think the students were proud that they’d done historical work that was real and valuable.”

As a summative assignment, the Grade 10 teacher let everyone choose how they’d commemorate some aspect of the Ward’s history. Those interested in science examined the impact of disease; others looked at it through the eyes of children. Some designed walking tours from the perspective of a child. Another proposed a statue of a family to acknowledge new Canadians who overcame a lack of money, education and language to build a better life.

“When I give students the opportunity to express their learning in a variety of ways, their engagement is way more committed than if I say, ‘Turn to page 65, answer the following questions.’”

Kimberley Snider, OCT, a teacher at Rosedale Heights School of the Arts in the Toronto District School Board and a collaborator of Whitfield’s, says that she’s brilliant at making history relevant. “It’s difficult for young people to connect with events that are so deeply in the past. Katy helps them make personal connections to what new Canadians went through in the Ward — whether coming to a new school or moving to a new country — based on their own experience.”

It’s no accident that the unit highlights voices that are typically absent from historical conversations — travelling gave Whitfield a strong sense of social justice. One student proposed an “anti-plaque” to commemorate the number of houses that were torn down and poor families displaced to build hospitals and a city hall. “I want to develop citizens who feel connected to their community and who care about the world,” says Whitfield. “History is about empathy and understanding.”

History without Textbooks

Award-winning history teacher Kathryn Whitfield, OCT, connects her Grade 10s to history through authentic, primary source documents. Here’s where you can find these resources:

Local Libraries

Visit in person or online to find Goad’s Fire Insurance maps, diaries (and other first-hand accounts), local census data, and secondary materials by historians and urban planners.

Toronto Public Library

Each branch has a local history collection with archived photos, maps, letters, newspapers, city reports and council meeting minutes. Some even contain a local historical society staffed by archivists. Visit in person or at torontopubliclibrary.ca.

Historical Societies

Study historic objects and artifacts that play an integral role in preserving Ontario’s heritage at one of hundreds of local societies (find yours at oct-oeeo.ca/1XqmPZt), or tap into teaching resources at ontariohistoricalsociety.ca.

Heritage Sites

Heritage sites often exhibit primary sources — in private heritage homes and national sites associated with Parks Canada, for example — that allow students to see historical documents within the context of their original spaces.

First Nations Elders

Did indigenous peoples first settle the particular land you’re studying? Talk to local elders, who can often share an oral history and answer questions you may not have answers for.