Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

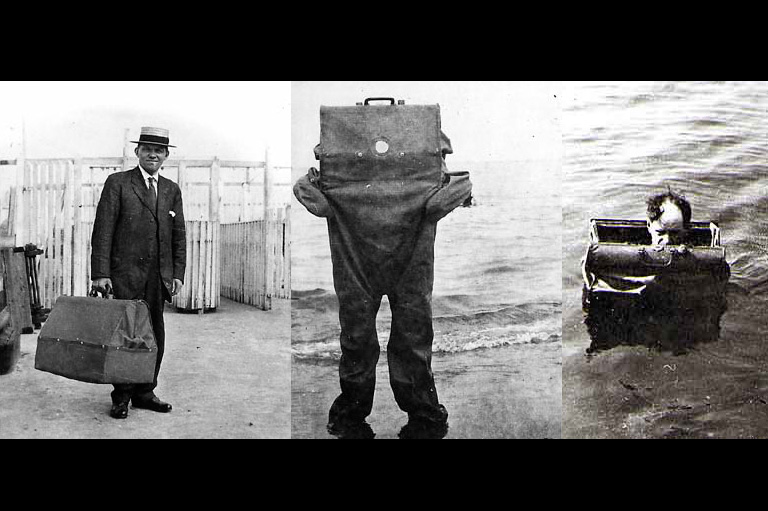

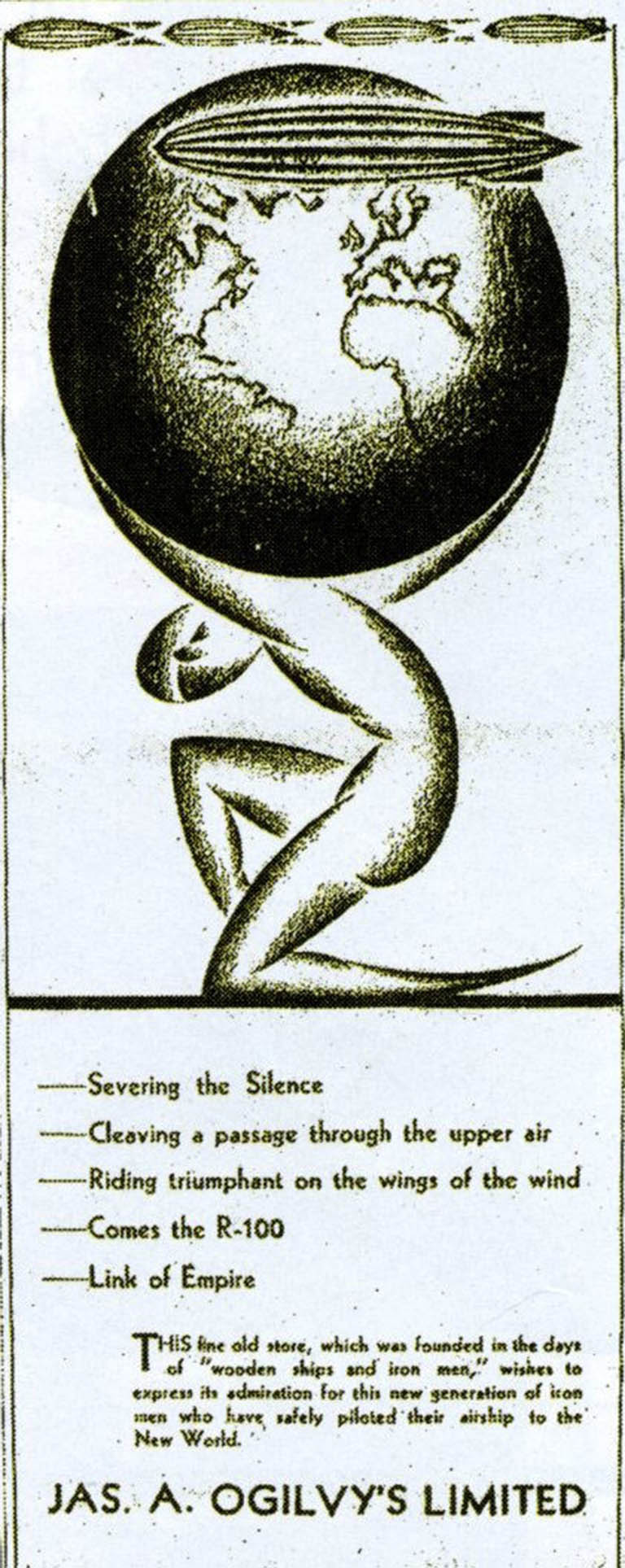

The First Dirigible in Canada

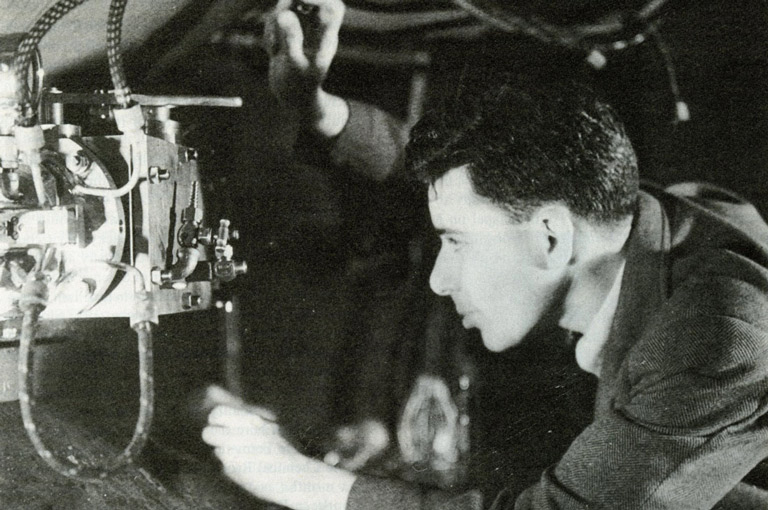

In the middle of the night, August 1, 1930, the passengers of the R-100, Britain’s new ultramodern airship, looked out into the misty night only to see “an enormous fiery cross” in the sky ahead. The cross, standing on the summit of Montreal’s Mount Royal since 1924, appeared to he floating in air.

His passengers’ anxiety and excitement was shared by those on the ground who had waited up since the previous afternoon in anticipation of catching a glimpse of the craft; when the newly installed searchlights at St. Hubert Airport fixed the R-100 in their beams, a hushed crowd burst into deafening cheers, and the sound of car horns resonated for miles.

The R-100 wasn’t the first airship to cross the Atlantic, nor was it the fastest, but on that hot summer night these details didn’t weigh on the minds of Canadians; the ship’s arrival stirred emotions like no event since the outbreak of the Great War. For the Canadian population, living through the disastrous first years of the Depression, the R-100, the first and only airship ever to visit Canada, offered a diversion from economic misery and inspired both national and imperial dreams.

British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald’s plan to build two airships, the R-100 and the R-101, as an experimental venture that would one day improve communications and transportation within the Empire. At the 1926 Imperial Conference, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, moved by a desire to participate in a great imperial project, promised that Canada would build a mooring mast on this side of the Atlantic.

The R-100’s arrival four years later marked the beginning of a fascination with the lighter-than-air craft; for the two weeks that the R-100 was in Canada, nearly a million people would visit the ship, over 70,000 travelling to St. Hubert Airport on a train that had been built in anticipation of the event.

The hundreds of journalists and politicians on hand for the landing unleashed their most powerful rhetoric: the voyage was “epic,” “majestic,” and demonstrated the enormous strength and prowess of the British Empire.

Bold predictions were made that, in the future, not only would dirigibles be twice as big and have a speed of at least eighty-five miles per hour, but that they would be flying from London to Montreal and back at least once a week.

For Montreal mayor Camillien Houde, the day of the R-100’s arrival would remain marked in his mind forever. “Heroes of courage, heroes of science, heroes of commercial development,” he proudly declared, “Canada’s metropolis is honoured to welcome you.”

The emotional outbursts that had greeted the ship in Montreal were repeated across Ontario as the R-100 made a twenty-five-hour voyage over the southern and eastern parts of the province. When seeing the R-100 flying over Toronto, the Canadian Forum could not control its emotional out-burst.

“The machine age,” the Forum reported, “which has filled our lives with noise and stinks and soul-cramping ugliness, can also give us things as poetically romantic as the R-100. Whether we can afford them or not, let us have all of them we can get.” Once the R-100 completed its flight over Ontario, it returned to Montreal, underwent repairs, and began to prepare for its return to England.

On Tuesday, August 12, 1930, the R-100 left Montreal for good, but a lasting imprint on its host country remained. For a moment at least, the ship’s arrival inspired Canadians to dream of a glorious present and a prosperous future.

It was not three months after the R-100’s return to England that the great hope of imperial airships was dashed forever.

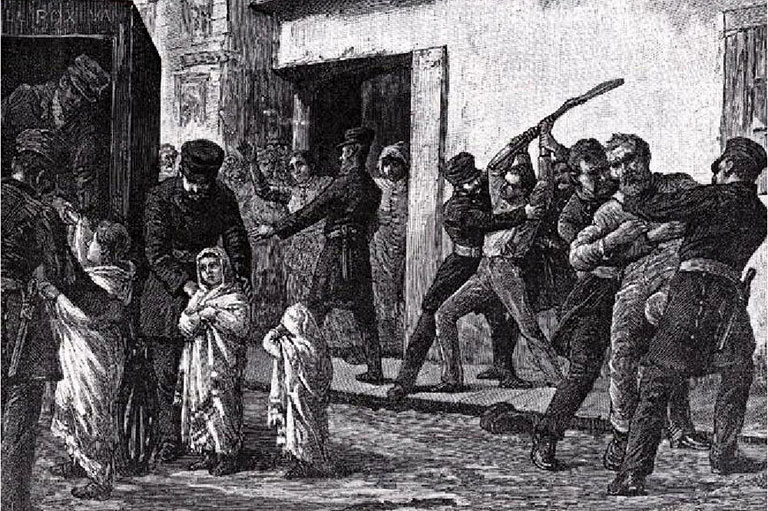

When the R-101, the R-100’s companion craft, left on its voyage to India, talk of airships one day connecting the far reaches of the British Empire was again in the air. While over France, however, the R-101 went into a prolonged dive, crashed into the side of a hill, and burst into flames.

News of the event, which killed forty-eight of the fifty-six on board, sent shock waves throughout the Empire that led to the demise of Britain’s airship program and forever grounded the R-100.

For Canadians, as they faced many long years of economic and political turmoil to come, the dreams of progress that the R-100 inspired crashed along with the R-100.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!