A Monstrous Plot

On Friday, Sept. 9, 1949, at 10:45 a.m., a fisherman near Sault-au-Cochon, 66 kilometres north of Quebec City, heard an explosion in the sky. Looking up, he saw a plane going down in the direction of Cap Tourmente. There was smoke, but no flames. Not far away, five men working on the Canadian National Railway line also heard the explosion and saw the plane crash onto a rocky hill. They raced through the bush to the site.

Story continues below...

Photo gallery

-

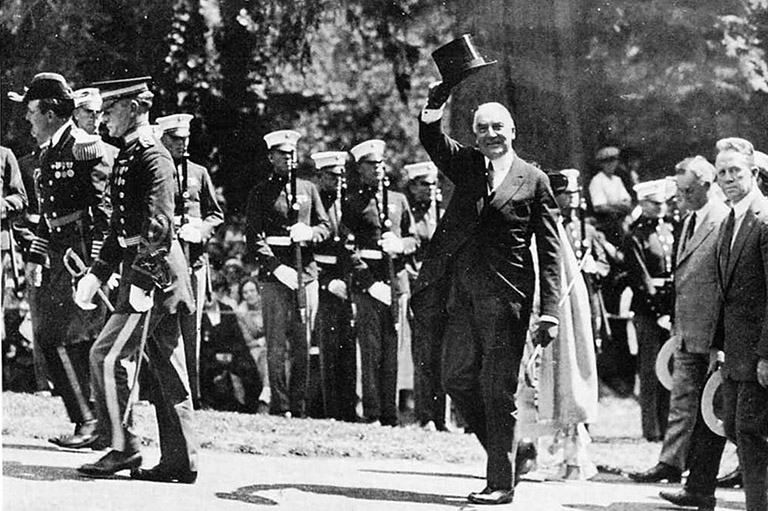

Minutes before takeoff, an amateur photographer took the above picture of the Canadian Pacific Airlines DC-3 that would take Rita Morel and 22 other passengers and crew to their deaths.Archives national du Québec

Minutes before takeoff, an amateur photographer took the above picture of the Canadian Pacific Airlines DC-3 that would take Rita Morel and 22 other passengers and crew to their deaths.Archives national du Québec -

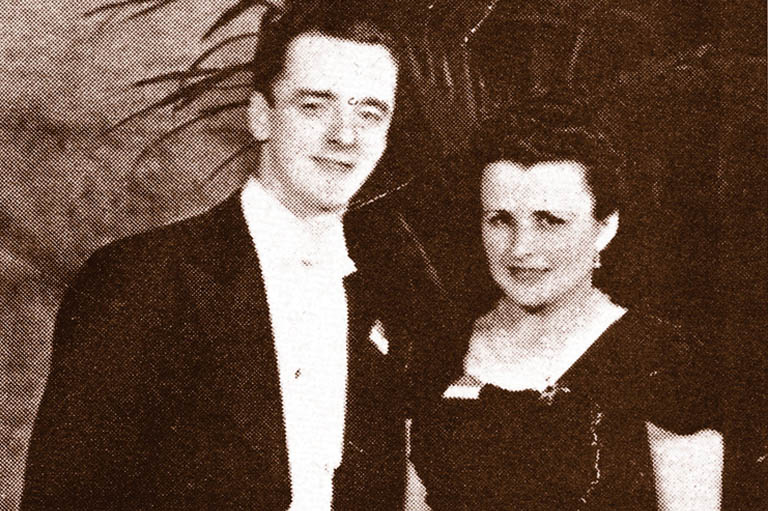

Albert Guay and his wife Rita Morel, during happier times.Archives national du Québec

Albert Guay and his wife Rita Morel, during happier times.Archives national du Québec -

Fragments of the exploded plane were presented at trial as part of the Crown's evidence against Albert Guay.Archives national du Québec

Fragments of the exploded plane were presented at trial as part of the Crown's evidence against Albert Guay.Archives national du Québec -

Dawn Huck

Dawn Huck

“Arms, legs, severed heads [were] lying around on the ground,” one of the men later told Montreal’s La Patrie newspaper. “The forward part of the plane looked intact. The bodies were piled up in there as if they had been thrown forward when the plane crashed. ... There was nothing we could do so we rushed out of the wood to alert the railway authorities.”

Soon, radio stations all around the province were broadcasting that a Canadian Pacific Airlines plane (flight number 108, according to some sources) had crashed near Sault-au-Cochon. The plane was a Douglas DC-3 flying from Montreal to Baie Comeau, on Quebec’s north coast. It had stopped at Quebec City to take on some pas sengers and was scheduled to resume its flight at 10:20.

It left five minutes late.

All 23 people on board — 19 passengers and four crewmembers — died in the crash.

A forensic analysis of the debris taken to Montreal concluded that the accident had been caused by a time bomb planted in the forward baggage compartment of the airplane.

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

In the days after the accident, Raymond Chasse, a journalist for Quebec City’s Le Soleil, reported that a mysterious “woman in black” had air-freighted a parcel on the ill-fated plane just before takeoff. Police soon identified the woman as Marguerite Ruest-Pitre, 43, of Quebec City.

She claimed the parcel was from a Mr. Delphis Bouchard of Saint-Simeon to a Mr. Albert Plouffe of Baie Comeau and that it had been entrusted to her by Albert Guay, a 31-year-old watchmaker and jeweller from Quebec City who employed her brother Généreux Ruest.

The police interrogated Bouchard, who denied having sent any parcel. No traces of an Albert Plouffe were ever found in Baie Comeau.

Sorting through the names of the crash victims, who included four children and three American business executives, police came upon Rita Morel, Albert Guay’s 29-year-old wife. Guay, they learned, had purchased the plane ticket for his wife and, at the same time, taken out a $10,000 insurance policy on her life.

In the days after the crash, Margaret Ruest-Pitre, or La femme Pitre, as she became known in the Quebec press, swallowed an overdose of sleeping pills. She survived, but under police questioning at the hospital, stated that Guay, in a state of near-hysteria, had told her that he had planted a bomb in the mysterious parcel and that she should kill herself because she was going to be blamed for the crime.

On Sept. 23, two weeks after the crash, Albert Guay was arrested and charged with murder.

In 1949, in-flight bombing was virtually unheard of. Four months before Guay’s arrest, two ex-convicts had planted a time bomb on an aircraft in the Philippines that resulted in 13 fatalities. It was one of the first incidents of its kind. The novelty of the explosion near Sault-au-Cochon had newspapers from all over North America rushing correspondents to Quebec City to cover Guay’s trial five months later.

Readers learned that Guay had married Rita Morel in 1940 and opened his jewellery and watch-repair shop in 1945, the same year they had their first child, a girl. Their happiness was short-lived; after these two events their marriage turned acrimonious.

Debts began piling up at the shop and Guay began having extramarital affairs. In 1948, he started courting 17-year-old waitress Marie-Ange Robitaille. Two or three times a week, he visited her at her parents’ home, where the teenager still lived. She introduced him to her parents as “Robert Angers,” hiding that he was a married man. Madly in love, he even bought her an engagement ring.

But Rita eventually learned of the affair. Incensed, she went to the girl’s parents where she confronted Guay and his teenaged mistress and told the Robitailles all about their daughter’s lover. The Robitailles threw their daughter out of the house, so Guay arranged for her to stay at the home of Marguerite Ruest-Pitre, a close friend of his, and her husband. Later he rented an apartment for himself and his mistress in Sept-Îles, 500 kilometres east along the St. Lawrence River.

From then on, he moved between mistress and wife — an arrangement that worked for neither woman. Fights in the Guay home became more frequent. Then young Marie-Ange decided to leave Guay. He was devastated. The idea came to him that if he could get rid of Rita, nothing would stand between him and happiness.

Divorce was hard to get in Catholic Quebec, so he elected to become a widower instead. In September 1949, he had a bomb made by Marguerite Ruest-Pitre’s brother, Généreux Ruest, a man crippled by tuberculosis and incapable of walking, but skilled at mechanical work.

He used batteries, an alarm clock and dynamite that his sister had bought at a hardware store. Then Guay convinced his wife to fly to Baie Comeau, telling her he needed her to pick up some jewels for his shop. (North coast mining communities such as Baie Comeau and Sept-Îles were boomtowns and business with them was flourishing.)

At the airport, Ruest-Pitre delivered the package containing the bomb to be air-freighted. The clock was set to trigger an explosion when the plane should have been flying over the St. Lawrence River, where the deep waters would swallow the evidence. Guay would be rid of his wife and have the insurance money to save his business from bankruptcy. But because the plane was five minutes late, it exploded over land, where police had an easier time studying the debris.

Guay was tried and convicted in February 1950. During the trial more damning evidence emerged: a man testified that in April 1949 Guay had offered him $500 to poison his wife. After his conviction, Guay issued a statement claiming that Ruest and Pitre acted knowingly to help him.

In June 1950, brother and sister were arrested and tried separately, Ruest in November, Pitre in March, 1951. Ruest first claimed he thought he was making a bomb to clear tree stumps from a field. Later, he said that Guay told him he needed the bomb to go “dynamite fishing.”

Pitre claimed she thought the package she delivered to the airport contained a statue and that she found out about the crime only after it had happened. Juries were unconvinced.

Albert Guay was hanged for the murder of 23 people in 1951. Le Soleil reported that his last words were “Bien, au moins, je meurs célébre!” (“Well, at least I die famous!) Généreux Ruest was hanged in 1952, Marguerite Ruest-Pitre in 1953.

She claimed her innocence to the end, but her appeal to the Supreme Court was rejected. She was the last woman to be hanged in Canada.

Out of the sky

Though airplane sabotage is a rare occurrence in Canadian history, it is the cause of Canada’s worst case of mass murder.

On June 23, 1985, Air India flight 182 en route to London, Delhi and Bombay from Montreal exploded 31,000 feet in the air over the Atlantic Ocean south of Ireland. All 329 passengers and crew on board, the majority of them Canadian citizens, were killed.

The explosion was caused by a bomb placed in the Boeing 747’s baggage compartment and constructed by a Sikh militant, Inderjit Singh Reyat. The Duncan, B.C. auto mechanic and electrician was retaliating for a 1984 attack by Indian government troops on a Sikh holy site in Amritsar, India.

The investigation and prosecution of those accused of the bombing took almost 20 years and, at $130 million, is the costliest in Canadian history. After pleading guilty to manslaughter in 2003, Reyat was sentenced to five years in jail. In March 2005, two others accused of the bombing, Ripudaman Singh Malik and Ajaib Singh Bagri, were found not guilty and were released.

Motive, means and opportunity were established in the 1949 Quebec airplane bombing and the 1985 Air India bombing, but Canada’s only other occurrence of airplane sabotage remains mostly a mystery.

On July 8, 1965, a Canadian Pacific Airlines DC-6B en route to Whitehorse from Vancouver exploded in the air near 100 Mile House, killing all 52 passengers and crew. The explosion ripped the tail section from the aircraft, sending both sections 15,000 feet to the forest below.

According to newspaper reports of the day, investigators found in the rear toilet traces of picric acid (trinitrophenol), an explosive that can be made relatively easily with store-bought chemicals, including acetylsalicylic acid (Aspirin). An inquest concluded that a high velocity explosion “foreign to the aircraft and its systems” ruptured the aircraft structure.

Who was responsible and why have never been established.

The Four Worst Air Accidents in Canada

Dec. 12, 1985. Gander, Nfld. An Arrow Air DC-8 en route to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, from Cairo, Egypt, with members of the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army, crashes on takeoff at Gander, Nfld., killing all 256 on board. Probable cause: icing on the wings.

Sept. 2, 1998. Peggy’s Cove, Nova Scotia. Swissair flight 111, a McDonnell Douglas MD-11 en route to Geneva from New York, crashes in the Atlantic Ocean nine kilometres from Peggy’s Cove, killing all 229 on board. Cause: in-flight fire.

Nov. 29, 1963. Ste-Therese-de-Blainville, Quebec. Trans-Canada Air Lines flight 831, a Douglas DC-8 en route to Toronto from Montreal, crashes five minutes after takeoff, killing all 118 onboard. Cause: undetermined.

July 5, 1970. Toronto. Air Canada flight 621, a Douglas DC-8 en route from Montreal crashes 11 kilometres from Toronto International Airport while trying to land, killing all 109 on board. Probable cause: pilot error.

Save as much as 52% off the cover price! 6 issues per year as low as $29.95. Available in print and digital.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement