Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

WWII: The Long Road Home

The Lancaster bomber shudders as bullets pierce the skin of its fuselage.

Someone shouts, “Bail out! Bail out!” — and then all is chaos. In an instant, Flying Officer Frank Rowan is tumbling from 18,000 feet, the wind screaming in his ears. As his parachute opens, slowing his descent, he is blinded by the flash of anti-aircraft fire and the inferno of Allied bombers bursting into flames.

He survives the landing but crashes into a fence, injuring his knee. Moments later, he hears the angry staccato of German voices, and just like that, Rowan — an Ottawa kid who joined the Royal Canadian Air Force because, well, his buddies from school were doing it, so why not him? — is a prisoner of war.

Almost sixty-five years later, Rowan sits at the dinner table in his Winnipeg home. Although he’s eighty nine years old, his eyes are clear and his voice is strong as he recalls the nightmare he survived decades ago.

It’s only when he’s asked about the mental anguish he endured afterwards that his voice lowers to a whisper and his recollection dims.

“When I came back, I’d get nightmares and all kinds of stuff,” Rowan says quietly. “I guess I had what they [now] call post-traumatic stress disorder.”

Rowan’s luck ran out, ironically enough, on March 17, 1945 — St. Patrick’s Day. Then twenty-four, he was a veteran flight navigator on a Lancaster bomber crew. On that day, the target was Nuremberg. It was Rowan’s thirty-fifth mission — and it was also his last.

Moments after dropping its payload, the heavy bomber was shot up by a German night fighter, likely a Messerschmitt Bf 110.

Rowan was captured immediately, interrogated, and then corralled with about two hundred other POWs. Soon, he and the others were marching eastward. They were barely on the road for a day when terror struck.

“We got strafed at ten in the morning,” Rowan recalls. “I had no idea what was happening. Thirty or more guys were hit at the back of the line. You could hear a bunch of people screaming.”

Rowan looked up and saw an American fighter plane. It had mistaken the POWs for German soldiers.

After it flew off, the German guards devised a quick — and final — solution for the wounded.

“The guys who were badly wounded, they just shot them in the back of the head,” Rowan says in disbelief. “Shot all the wounded. That was the last time we walked in daylight.”

Such horrors were to become routine on the journey. Rowan and his companions were among more than 80,000 POWs driven eastward during the “death marches” of the winter and spring of 1945. For some, death came quickly and without warning.

On one occasion, a German guard lost control of his Doberman and it attacked a prisoner. “We were just struggling along when one of the dogs broke loose. The dog leaped up and got him in the throat,” Rowan says, his voice rough with emotion. “An officer came back, spoke less than five minutes, and then shot the dog. He spoke another five minutes, and then shot the guard, put a blanket on him, and we kept on walking.”

Rowan quickly learned to keep his head down and his mouth shut to avoid attention.

“I just wanted to get home,” he says. “That was my main aim — to stay alive.”

The POWs survived on a thin broth of water and boiled onions. Famished, the men lamented the food they had left uneaten during Christmas and New Year’s dinners. Many died on the road, either from their wounds or from diarrhea or other illnesses. Rowan winces as he recalls one particularly gruesome duty he was called on to perform involving the corpses of Allied prisoners.

“We helped them pile the bodies together. They poured petrol, or benzene, as they would say, and cremated them right there. I saw that repeated a number of times.”

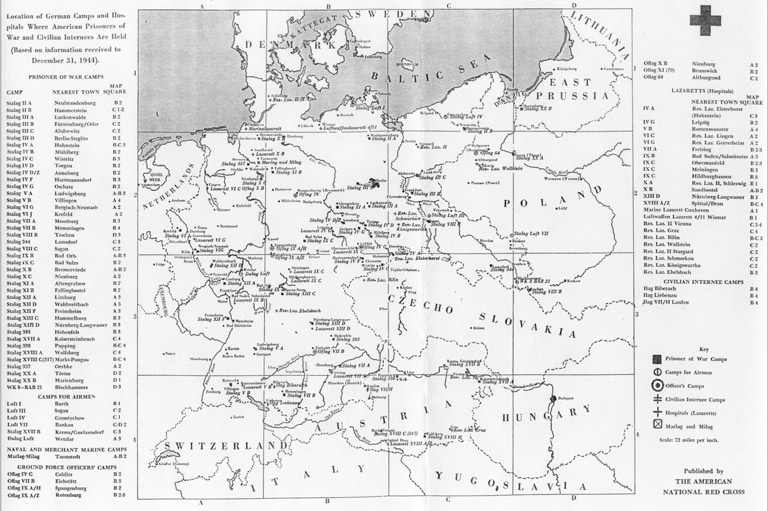

They staggered across Germany for forty-five days until they finally arrived at a POW camp near the Czechoslovakian border, somewhere northeast of Stalag VII A, a major camp in the Moosburg region of southeast Germany. It’s possible the camp was either Stalag 383 or Stalag XIII D — Rowan isn’t sure.

Fortunately, Rowan’s capture came at the very end of the war in Europe. Just as he arrived at the prison camp, Germany surrendered. Suddenly, he was on the march again as his German captors sought to turn over the prisoners and surrender to the Americans rather than face the wrath of the Russian army advancing from the east. Roughly seven days after VE day, Rowan and the others met up with the US Third Army commanded by General George Patton. The German guards surrendered and Patton immediately ordered his men to shoot all of the Dobermans and German shepherds.

Rowan said the Americans warned the POWs not to enter any nearby buildings, because they were likely booby-trapped. “It’s amazing how many chaps got killed,” Rowan says, shaking his head. “Some went into the washroom and were killed by explosions.”

Rowan is about to begin another story when his wife Anita enters the room. He greets her with a broad smile; together sixty-four years, they were sweethearts when Frank went off to war.

Anita returns the smile. Back in 1945, she believed she would never see Frank again, especially after military officials broke the news to Frank’s mother of his “death” over Germany.

“By then my mother had long given up hope,” Rowan says. “She had spoken to the padre and everything. As far as they were concerned, I was gone.”

Rowan remembers stepping off a train in Montreal and seeing Anita and his mother standing there with tears spilling down their cheeks. With his head shaven, and his body emaciated after losing more than thirty-five pounds on the march, he jokes that the women “were sort of disappointed to see me the way I was!”

However, the joy of his return was muted by the nightmares that plagued his sleep. Exhausted and suffering from stress, he sought medical help. He was sent to Eaton Hall, a convalescent home for veterans located at the Muskoka, Ontario, summer estate of Lady Flora McCrea Eaton, a former nurse and the widow of department store president and heir Sir John Craig Eaton.

While Rowan remembers plenty of details about his time as a POW, his recollection of his medical treatment isn’t as sharp. “There were lots of tents,” he says. “It was very nice, well organized. They had nurses and doctors, and they treated us just like a child — oatmeal in the morning, lots of rest.” Frank recalls fondly the nurses massaging his feet, which had been torn up during the forced march. Doctors also ordered him to take barefoot walks in the grass as part of his treatment.

After about a month, they declared him cured and sent him home, with a warning: Stay away from anything that reminded him of war, including veterans’ organizations. And so he did.

“I just never dwelt on it. Never,” he says. “Terrible things happened there. There was just not much to talk about. And friends of mine who were veterans — not one of them spent five minutes talking about their experiences.”

Frank married Anita in 1946 and went to university. After graduation, he enjoyed a long and successful career in a variety of positions, including a role as an official with the Canadian Wheat Board who helped open up foreign markets to Canadian farmers.

For forty-three years, he basically willed himself to forget the war. But in 1988, at the urging of a former Lancaster crew mate, Rowan finally relented and joined the Wartime Pilots and Observers Association. He says it’s one of the best decisions he ever made. He remains an active member and cherishes the friendships he’s forged with fellow vets.

Today, Frank’s walls are filled with photos of his grandchildren. All things considered, he counts himself a lucky man. Declared dead by the military, he was given a second chance at life — a chance he made sure not to squander.

“When people ask me how old I am, I tell them I just count my blessings, not my birthdays,” he says. “We are very fortunate what we came through. Very fortunate.”

Map of German Prisoner of War Camps

Approximately 9,000 Canadians were captured by the enemy and held as prisoners of war (POWs) during the Second World War. Most of them were kept in German POW camps and were forced to endure long marches with meager rations, especially toward the end of the war.

But the nearly 1,700 Canadian POWs held in Asia faced worse conditions. The Japanese camps were often extremely brutal, providing very little food and forcing back-breaking manual labour in Japanese mines and shipyards.

To take a closer look at this map showcasing German POW camps that held Canadians during the Second World War click here.

Themes associated with this article

Read the series

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!