Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Roots: Meet Your Marker

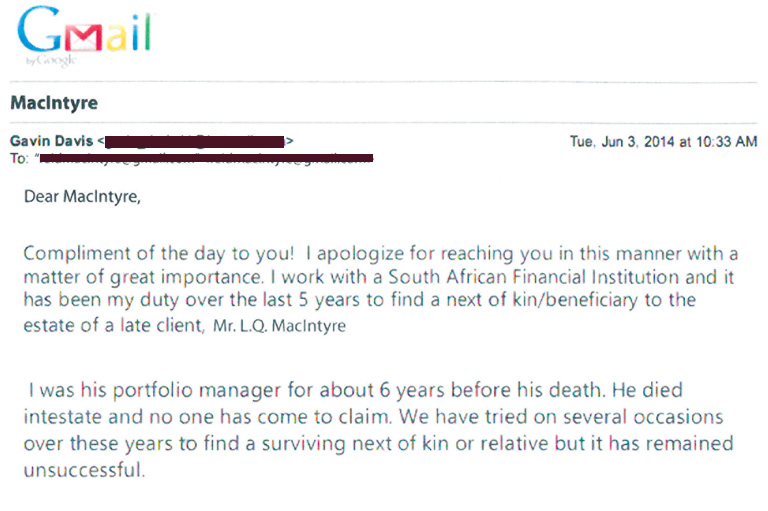

My friend Elizabeth is thrilled. An adoptee, she has almost certainly identified her birth father after a search of more than forty years. Little did she realize that the truth would be extracted not from a musty register or an octogenarian’s fading memories but from the sequencers and analyzers of a state-of-the-art laboratory. Through DNA testing not available to the public just three years ago, researchers like her are now resolving formerly hopeless family history problems.

Until recently, genetics offered limited utility to genealogists. True, DNA testing occasionally exhibited immense potential, as in the demonstration that Thomas Jefferson (or a close male relative) fathered at least some of the children of his slave Sally Hemings. But it also had unfortunate limitations. The most robust tests applied only to DNA inherited through strict paternal or maternal lines of descent — for instance, a father’s father’s father or a mother’s mother’s mother.

Too bad if you were attempting to prove a match to your mother’s father’s father, or your father’s mother’s mother, or some other ancestor who deviated from the strict male or female lines. As a case in point, fully ninety per cent of our Victorian-era forebears are not connected to us through strict paternal or maternal lines.

Some tests claimed to identify a broader range of relatives, but they were severely, if not totally, compromised by the paltry number of DNA markers analyzed by the technology of the time.

Genealogists became experts at reframing their problems so that the available tests could be made to apply. Women would routinely recruit their fathers, brothers, or paternal uncles as surrogates to explore their patrilineage. This tactic remains useful in exploring the paternal line.

Men are somewhat luckier in that they carry the particular DNA required for a maternal-line test — they just can’t pass it along to the next generation. As I write, this wrinkle may prove conclusive regarding a recently unearthed skeleton conjectured to be the remains of England’s Richard III. If DNA can be extracted, it will be compared with a present-day sample taken from a matrilineal descendant of one of Richard’s sisters. This plan presupposes that there is an uninterrupted family line from the fifteenth century that will allow ready identification of today’s living descendants.

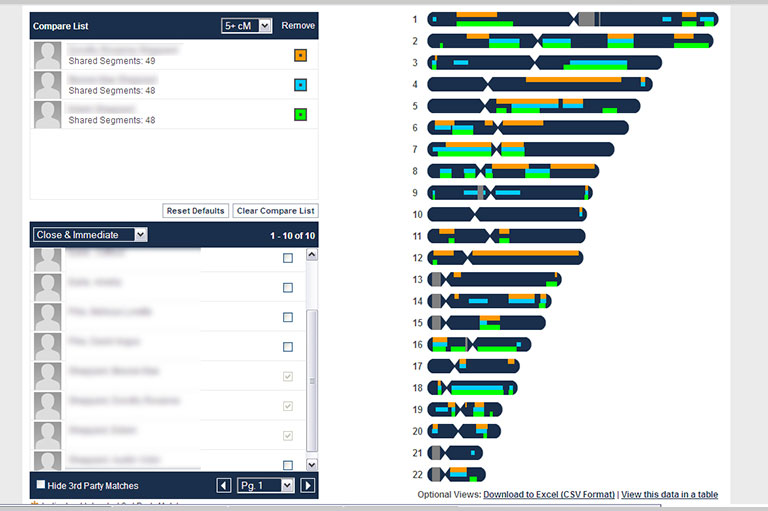

So what’s changed to remove the irksome restriction to paternal and maternal lines? First of all, the technology. DNA analysis is now so turbocharged that hundreds of thousands of locations across one’s genome can be checked without having to remortgage your home. The service I use examines more than 700,000 of these markers for US$289 per person. This huge sample allows detailed calculations to determine the probability, with a high measure of confidence, of the degree of relatedness of two individuals. We get clear-cut and statistically credible predictions that two individuals are siblings, first cousins, second cousins, and so on.

Secondly, a critical mass of people — estimated to be into the hundreds of thousands — has now taken such tests. My 700,000-plus markers are pretty meaningless to me in isolation. Only when compared to other profiles do they assume significance. Through the database assembled by my testing company, I now have access to newly discovered third and fourth cousins with whom I can work on our joint family trees. Perhaps these distant relatives have different family stories, documents, and heirlooms that can enrich my own research. Over time, as more and more people do the tests and end up in the database, I will be introduced to increasing numbers of “lost” cousins.

More dramatic, though, are breakthroughs that would have been unthinkable via conventional research. In his recent book, Finding Family, genealogy blogger Richard Hill details his quest to find his birth parents after a chance 1964 disclosure that he had been adopted. By late in the last decade, Hill thought the matter had been resolved; but he was wrong, deceived by the limited statistical reliability of early DNA analysis. Finally, earlier this year, the most powerful DNA test on the general market provided unarguable confirmation of the last pieces of the puzzle: the true identity of Hill’s biological father and half siblings.

Discoveries like this change lives, not just for the researcher but also for newly found family members. Elizabeth and her new half sisters can’t wait.

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!