Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

Regina's Day of Wrath: The Killer Cyclone of 1912

“Cyclone hits Regina. City in ruins.”

That six-word message, received in the Winnipeg Telegraph Office shortly before five p.m. on Sunday, 30 June 1912, announced the most destructive cyclone in Canadian history.

Technically, according to the meteorologists, the storm which hit the city at ten minutes to five that day was a tornado. In Regina, it has always been popularly known as “the cyclone.”

Article continues below...

-

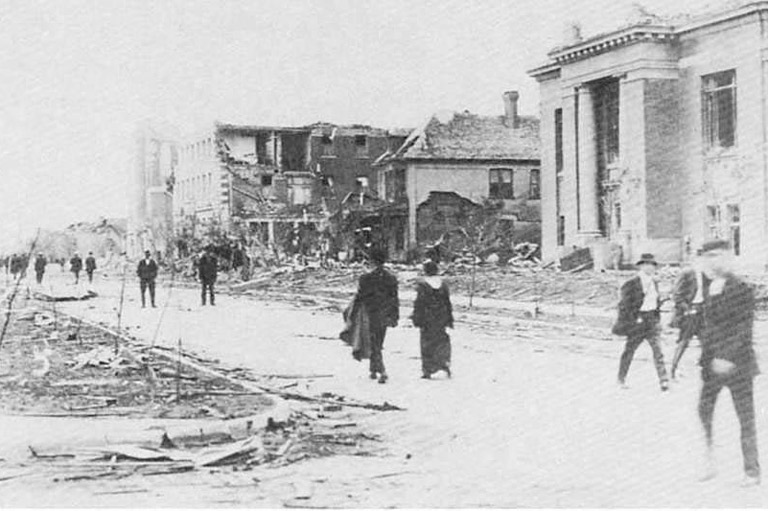

Lorne Street looking south, showing the Metropolitan Methodist church, the Y.W.C.A. and the Public Library. Citizens survey the damage after the storm.Saskatchewan Archives Board

Lorne Street looking south, showing the Metropolitan Methodist church, the Y.W.C.A. and the Public Library. Citizens survey the damage after the storm.Saskatchewan Archives Board -

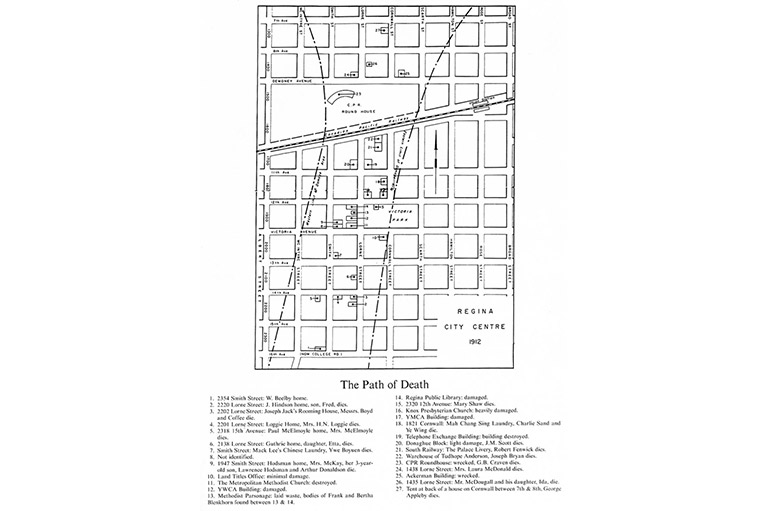

Path of Death. Legend to area damaged by the storm.

Path of Death. Legend to area damaged by the storm. -

Eleventh Avenue looking west, a scene of terrible destruction.Saskatchewan Archives Board

Eleventh Avenue looking west, a scene of terrible destruction.Saskatchewan Archives Board -

Survivors sift through the rubble of heavily damaged homes on Smith Street.Saskatchewan Archives Board

Survivors sift through the rubble of heavily damaged homes on Smith Street.Saskatchewan Archives Board -

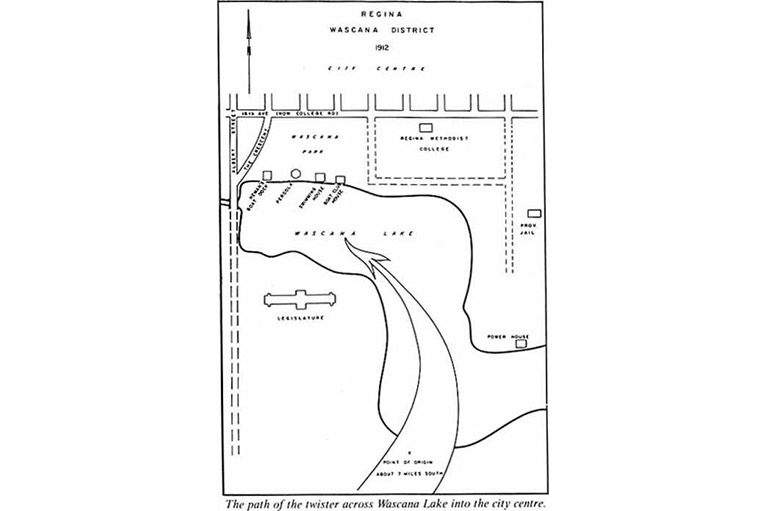

The path of the twister across Wascana Lake into the city centre.

The path of the twister across Wascana Lake into the city centre.

Crossing the centre of the city from south to north in a rampage that lasted fewer than six minutes, the cyclone left twenty-eight dead, hundreds injured, thousands homeless and over $5 million in property damage (about $75 million in 1993 dollars) — all in a city with a population of 30,000.

A little before 5 p.m., the Power House whistle blasted a warning to the citizens. This was just over five minutes from the time the cyclone had swept in across Wascana Lake between the Power House and the newly constructed Legislative Buildlings.

Unfortunately, by the time the warning sounded, the storm was over, except for the accompanying torrential downpour that dumped over an inch of rain mixed with hail in the next half-hour or so. The rain had the beneficial effect of keeping the fires down.

Despite the fact that two or three tornadoes are reported in Saskatchewan every year, nothing approaching this magnitude of destruction has been seen since.

The damage done by the storm was concentrated along a narrow path through the centre of Regina between three and four hundred yards wide — barely three blocks — and nine blocks long. Within that small area, close to five hundred buildings were destroyed.

The rest of the city remained virtually untouched.

On Smith Street, houses on the west side were unaffected to the extent that potted plants on open verandas were not even blown over. The houses on the east side of the street were reduced to rubble.

Lilian Vaux MacKinnon in an unpublished memoir notes that “The first indication for half the city — cyclones cut a narrow path, you know — was to see cars and firetrucks with the wounded making for the hospitals.”

As it passed the Legislative Buildings, which were only lightly damaged, the cyclone sucked out ail the examination papers for all Saskatchewan grade schools for the year. Throughout the province, teachers had to pass or fail their pupils on the basis of their recollection of how well they had done during the year.

As it swept across Wascana Lake headed for the centre of the city, the cyclone created a gigantic waterspout. The Boat Club House by the lake was demolished. All those who had sought shelter in it were severely injured and one was killed.

The Beelby family, at 2354 Smith Street, took refuge in their attic. The cyclone neatly tore if off the house and carried it with all its inhabitants over one hundred and fifty feet and deposited it in a neighbour’s yard. None of the Beelbys, who climbed out a window, was hurt.

Four blocks further north, at 1947 Smith Street, the home of the Hodsman family, they were not so lucky. When the front wall of the house collapsed, three roomers and one of the Hodsman children were killed.

Arthur Donaldson, one of those roomers, had been out walking his dog, a small, brown mongrel. He rushed towards the house as the storm roared up and was killed as it was reduced to rubble. The dog was blown past. After calm had returned, the dog came back to the ruined house.

He watched as the rescuers dug through the wreckage, then followed when the body of his master was taken to the Speers Funeral Parlours. From Sunday to Wednesday when his master was buried, the dog kept vigil. After that, he disappeared.

After destroying hundreds of houses as it rolled up Lorne Street, the cyclone destroyed Knox Presbyterian and the Metropolitan Methodist churches and tore the cupola off the Baptist church. Then the Regina Public Library, which had opened only one month earlier, had its roof taken off.

The Reverend Doctor James Falconer, visiting from Pine Hill College, Halifax, had preached in Knox church that morning. He “was sitting on an upstairs veranda and he suddenly called his hostess, ‘I thought the Methodist Church was over there! Now I can't see it!’ Absolutely demolished it was. And the parsonage to it.”

Perhaps the most poignant deaths were those of Frank and Bertha Blenkhorn. Married in England in early April, they had booked their wedding voyage on board the Titanic. But their wedding party went on so long, they missed its sailing on the evening of 12 April. However, they took a later boat and were in Regina on the afternoon of 30 June.

As Frank and Bertha walked across Victoria Park, the full fury of the cyclone hit. They were picked up and tumbled almost two hundred yards across Lome Street. Their lifeless bodies were found between the destroyed Methodist parsonage and the now-roofless Carnegie Library.

The Telephone Exchange Building, at the corner of Lome and Eleventh Avenue, was virtually destroyed. The roof was blown off and the south wall collapsed. Then the weight of the switchboard broke through the floor on the second storey, carrying three women and one man all the way down to the basement.

None of them was seriously injured and they managed to climb out through a window. When they appeared at the offices of the Regina Leader to tell of their narrow escape, they were not believed. The reporters merely thought they wanted to see their names in print.

The mercantile and warehouse district from South Railway Street north to Dewdney received the full brunt of the storm. C.R. Delerue described the destruction: “Not only was one elevator laying across the tracks, but four more besides . . . [in] the railway yards. .. [there was] not a single car upon the tracks ... a great brick warehouse on the other side of the tracks was missing.”

Mrs. MacKinnon recalls “how devastatingly hot it was the week before. The heat seemed pitiless.” When the storm hit, her sister and her husband’s brother, Hugh, were guests. When Hugh returned after the storm, “he found [her] sister dazed on the veranda, trying to pack things strewn about into a trunk which had been in the attic.”

Earlier, Hugh had run upstairs to close the windows at the sight of the approaching storm. “The window went from him as he touched it. All the windows were blown out. That’s what relieved the pressure or the walls would have collapsed as in many homes. The roof went too. Me saw it at the bottom of the block when he came to himself... he doesn’t to this day know how he got downstairs. But the moment he was out of the house he was caught up and hurled away down the street.”

Mrs. MacKinnon, her husband, sister, and two children had sheltered in their house initially, first by the bay window, later in the basement. When they emerged, “suddenly there was Uncle Hugh with his head all cut and we had to use Aunt Emma’s petticoat for bandages ... Petticoats in those days were long and frilly and very private. But she undid the belt and let it fall right down, and tore a strip.”

C.R. Dclcrue was staying at the Clayton Hotel. At the approach of the storm, he had rushed to the top floor of the building to close windows. He observed “heaps of girls ... in hysterics. The fellows were as white as ghosts. How I got down to the next floor, I don't know, but I did and found my way to the piano and played for all I was worth and drowned my fears.”

Once the storm had passed, Delerue went out into the streets to chronicle the damage. “Pretty well every plate glass window in the city was broken, and the rain had just played Old Harry with the merchandise ... the magnificent churches of the morning [were] in ruins ... Knox Presbyterian church looks ... just like an old English ruin.

“The YMCA and YWCA buildings, which were only recently opened, were terribly delapidated [sic] . . . Lome Street . . . was . . . strewn with all kinds of goods, telegraph poles, trees, lumber, glass and parts of furniture and clothing.”

On a walk the previous day, Delerue had admired the houses on Lome, “one might almost call them mansions. . . Now there were seventy or eighty as flat as a pancake. There wasn’t a post standing. . . It was impossible to recognize that houses had stood there.”

Finally, he noted that “People were running this way and that, screaming. . . Other people were dragging the injured out. . . Soon . . . every available vehicle was pressed into service and they made for the hospitals with the injured.”

Alerted by telegraph from Winnipeg — all the functioning lines from Regina led cast — the first relief from outside was a train from Moose Jaw that arrived at the Exhibition Grounds around 7:15 P.M., loaded with doctors, nurses and medical supplies. A train from Winnipeg arrived early the next morning.

One of the first groups to respond to the need for financial assistance was a visiting American theatrical troupe, the Albini-Avolo Company, who were performing at the Regina Theatre. The troupe included a then-unknown Boris Karloff.

The afternoon of the storm, they had been on a picnic out along Wascana Creek and were unaware of what had happened until they returned later that evening. They staged a benefit performance of the comedy The Real Thing in Regina. The following week, they donated half the proceeds from their performances in Saskatoon to the relief effort.

Before the cyclone hit, Regina had been readying itself for the next day’s Dominion Day celebrations. After it, late in the evening, the Mayor, Peter McAra, issued a proclamation, “In view of the terrible happenings of today, I deem it my duty to declare all [celebrations] indefinitely postponed; I also request that all the bars of the city hotels remain closed for the day.”

The mayor’s order was duly carried out and 1912 became the only year in Regina’s history with no Dominion Day celebrations.

At Canada’s History, we highlight our nation’s past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, while understanding that diverse past experiences can shape multiple perceptions of our history.

Canada’s History is a registered charity. Generous contributions from readers like you help us explore and celebrate Canada’s diverse stories and make them accessible to all through our free online content.

Please donate to Canada’s History today. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!

Beautiful woven all-silk bow tie — burgundy with small silver beaver images throughout. This bow tie was inspired by Pierre Berton, inaugural winner of the Governor General's History Award for Popular Media: The Pierre Berton Award, presented by Canada's History Society. Self-tie with adjustments for neck size. Please note: these are not pre-tied.

Made exclusively for Canada's History.