The War of the Nickel Bar

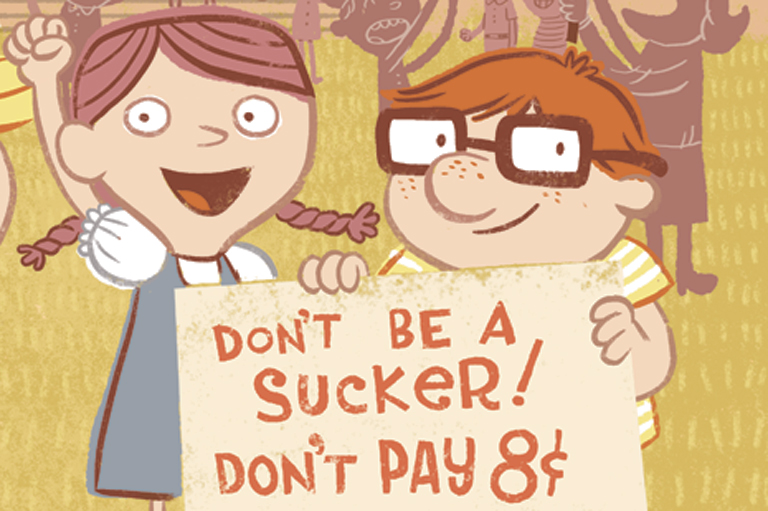

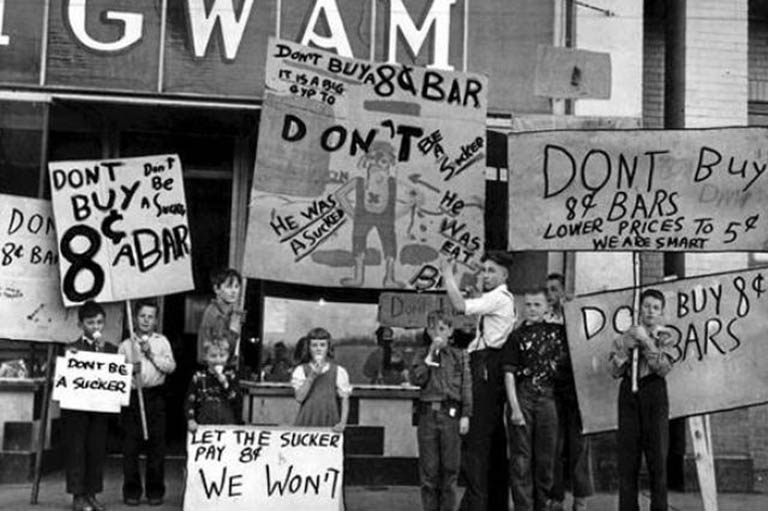

On April 25,1947, a call to arms resounded across Canada following the relaxation of wartime price controls, when chocolate manufacturers raised the price of chocolate bars by sixty percent. The sleepy Vancouver Island towns of Chemainus and Ladysmith erupted into battlefields, as the children of war-weary veterans bandied together for cheaper candy and descended upon confectioners armed with placards bearing slogans like “Don’t be a sucker. Don’t buy eight-cent bars!”

Article continues below.

-

Kids protesting in front of the Wigwam Cafe in Ladysmith, B.C.Vancouver Sun

Kids protesting in front of the Wigwam Cafe in Ladysmith, B.C.Vancouver Sun -

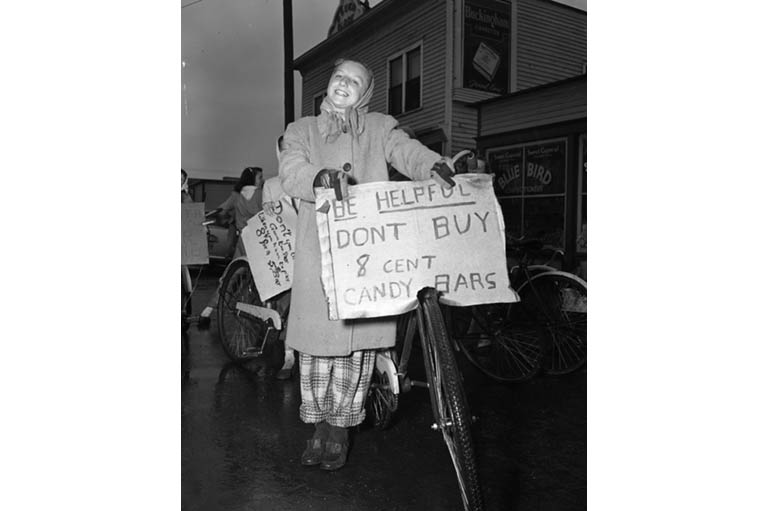

Kids on bikes and on strike... signs say "Be helpful, don't buy 8 cent bars" and "Go on strike."Edmonton Journal

Kids on bikes and on strike... signs say "Be helpful, don't buy 8 cent bars" and "Go on strike."Edmonton Journal -

Kids who had bicycles would pedal around town to drum up support for their cause.

Kids who had bicycles would pedal around town to drum up support for their cause. -

Girl sitting on a fence with her placard "What this country needs is a good 5 cent bar."

Girl sitting on a fence with her placard "What this country needs is a good 5 cent bar." -

May 6, 1947: Hard to resist the lure of chocolate.Globe and Mail

May 6, 1947: Hard to resist the lure of chocolate.Globe and Mail

This adolescent war cry reverberated all the way east to Fredericton, New Brunswick, as kids arose with a unified voice demanding the return of the nickel bar.

For ten days, these young dissenters captured front-page headlines and the hearts of adults, as they defied rampant inflation and manufacturers they regarded as ruthless. The Regina Leader-Post dubbed the eight-cent-bar protest “a symbol for all excessive prices.” Newspaper editorials questioned the integrity of the manufacturers after a deluge of eight-cent chocolate bars flooded a market that had been bar barren before the price surge. Even empathetic confectioners supported the movement, refusing to stock eight-cent bars and selling their existing stock at a loss for five cents.

Along with the media, the eight-cent-chocolate-bar protest won the support of numerous youth organizations, including the National Federation of Labour Youth, which boasted seven thousand members nationwide.

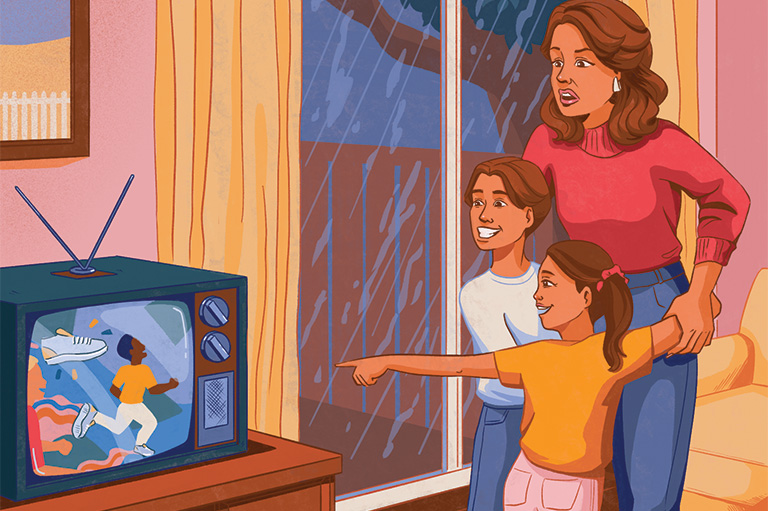

While the public rallied around the disgruntled kids, chocolate manufacturers grappled desperately to restore their crumbling public image by battling their opponents through the daily newspapers. They insisted that the loss of war contracts, elimination of cocoa bean subsidies, and rising costs in labour, packaging, and ingredients had increased manufacturing costs by over 165 percent, necessitating the sixty percent price increase. Meanwhile, cagey confectioners moved their chocolate goods from beneath the glass counters onto the countertops, desperately trying to mitigate the eighty percent slump in chocolate-bar sales. Some strikers succumbed to this ploy, bought bars, and lost friends.

Five days after the initial protest, Victoria’s staid legislature ground to a halt when two hundred schoolchildren stormed the hallways demanding five-cent chocolate bars. On the other side of the nation, in Fredericton, protesters satiated their need for chocolate by pooling sugar rations to make communal batches of fudge.

A decisive battle was set for May 3 in every major city across Canada. Excitement mounted amongst the hopeful protesters as they busily painted placards, shined whistles, polished bicycles, and copied petition forms.

But the postwar anticommunist hysteria, which Senator Joseph McCarthy would bring to its apex in the U.S. in the early 1950s, was already breeding in the Canada of 1947. Under the headline “Reds Seen Duping Youth in 8-Cent Bar Campaign,” the Toronto Telegram claimed the day before the scheduled protest that “Chocolate bars and a world revolution may seem poles apart but to the devious Communist mind there is a close relationship.” The article alleged that the National Federation of Labour Youth, which gave the protest its powerful thrust, was a communist-front organization that had infiltrated the protest “to foment any kind of strife since that is the party line … and to gain the confidence of at least a proportion of the strikers and plant a few of the seeds of Marxism.”

This bloated allegation achieved its desired affect by dissolving the public support the protesters had previously enjoyed. Suddenly parents, priests, and public officials phoned youth organizations to denounce the protest and demand the groups call it off. Numerous groups, frightened by the communist allegations and cowed by public reproach, rescinded their support. The National Federation of Labour Youth was effectively destroyed.

On the battle day, a few sheepish protesters marched, but the vaporization of public support had deflated the movement. In Victoria, one of the heaviest battlefronts, a handful of well-groomed children quietly marched through downtown Victoria, obediently pausing at intersections to avoid obstructing traffic.

And so the movement ebbed, and the demoralized children, bowled over by unsubstantiated accusations, surrendered to the insatiable demands of inflation. One week after the protest, the groups that had marched vowed they would stage no more demonstrations because communists had moved in.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement