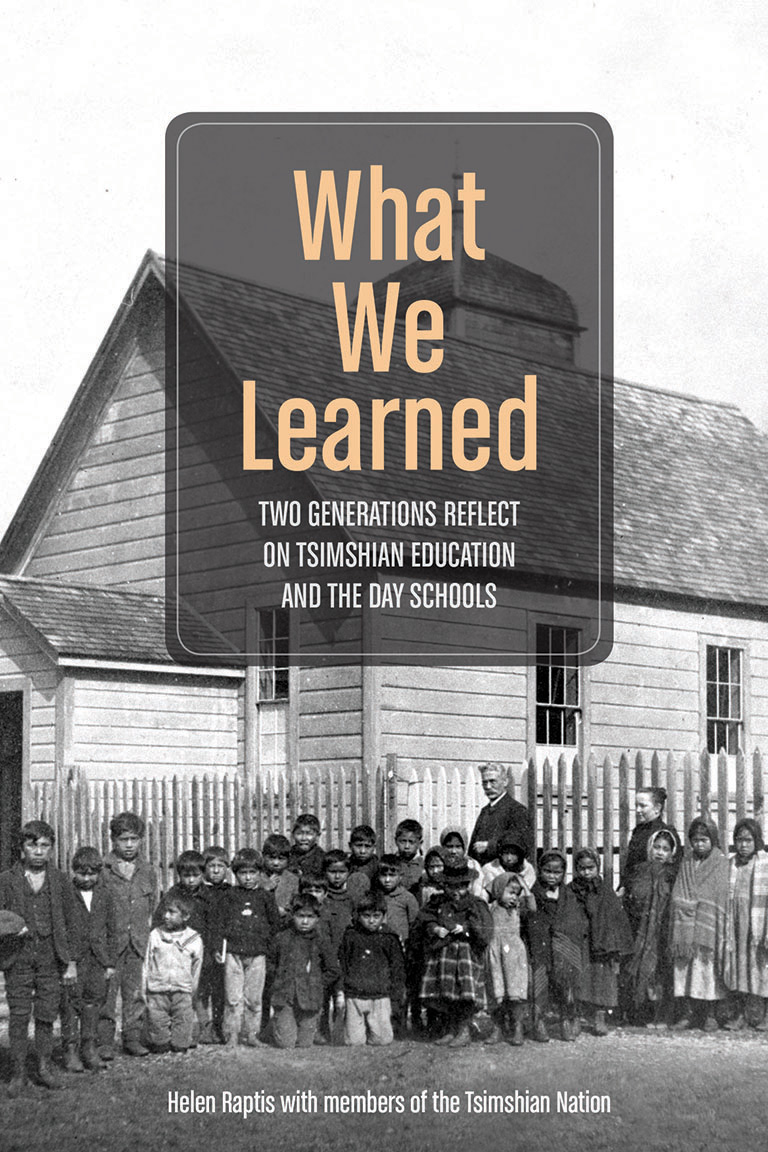

What We Learned

What We Learned: Two Generations Reflect on Tsimshian Education and the Day Schools

by Helen Raptis with members of the Tsimshian Nation

UBC Press

223 pages, $32.95

Too many stories are still untold; too many memories have been lost to the ages; too many biases have coloured our view of the past. That is why a book such as this one is a treasure, an overdue and culturally aware look at a forgotten aspect of the education of Indigenous children in British Columbia.

While the history of residential schools has become well-known in recent years, those were not the only schools attended by First Nations children. Many attended “Indian day schools” that had been set up in their own communities but were separate from the public schools attended by non- Indigenous children.

The day school featured in What We Learned: Two Generations Reflect on Tsimshian Education and the Day Schools was in Port Essington, on the Skeena River near Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Students from Port Essington also attended public schools there and in Terrace, as well as residential schools.

Author Helen Raptis, an associate professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Victoria, took great care to create a respectful relationship with the former students and to ensure that their stories are presented with an acknowledgement of traditional Tsimshian ways of teaching. Her account of that effort could be a guide to future historical efforts among Indigenous communities.

In this book, former students Mildred Roberts, Wally Miller, Sam Lockerby, Verna Inkster, Clifford Bolton, Harvey Wing, Charlotte Guno, Don Roberts Junior, Steve Roberts, Richard Roberts, Carol Sam, and Jim Roberts offer their perspectives on education.

The day school in Port Essington was closed in 1947, four years before the federal government officially ended segregated schooling in 1951. The number of students attending the non-Indigenous public school had dropped so low that it seemed pointless to have two schools. In the 1960s, two major fires meant most residents of Port Essington moved away, with many going to Terrace.

In Port Essington, students lived with their families within walking distance of school and were often able to go home for lunch. That changed when they had to attend public schools, which were much less personal.

There are also differences in the experiences of the students. The earlier generation going to day schools experienced more abuse in the education system than the later one did, but the later generation that went to public schools faced more discrimination. The earlier generation was able to retain more of the Tsimshian culture, language, and values.

The former students who worked with Raptis tell of good times, such as learning skills they used for the rest of their lives, and of bad times, such as being forced to speak English rather than their own languages. It can be hard for an outsider to understand what it must have been like for these students, who were expected to conform to unfamiliar rules and meet unfamiliar expectations, but this book makes it possible to appreciate what the children went through and the impact the experience had on their lives.

Raptis lists all of the teachers who taught at the day school and includes basic biographical information on some of them. Not surprisingly, it was difficult to find and to retain qualified teachers for a relatively isolated school. Does that justify the fact that a teacher who admitted to sexual interference with three boys did not face criminal charges? No.

Official records usually deal with administration and buildings, not with people. What We Learned helps to close that gap and promotes a greater understanding of the impact of an education system that was imposed on Indigenous peoples.

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement