A National Anthem is Born

June 24, 1880: Picture a palatial ballroom in Quebec City, lit by gas lamps, on the night of St-Jean-Baptiste Day.

Five hundred guests are on hand for a banquet — the crowning event of an international gathering of the French from across North America. The governor general is here, along with Quebec’s lieutenant governor and the Honourable Wilfrid Laurier, plus senators, judges, mayors, and delegates from across Canada and New England. They sit at six long tables laden with delicacies: salmon, turkey, capon, roast beef, and lobster salad. For dessert are ices, creams, and pies of strawberry, peach, raspberry, rhubarb, and plum.

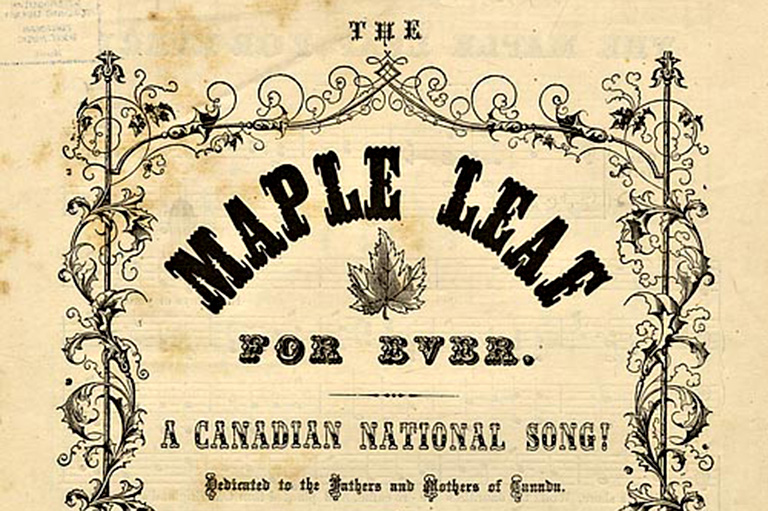

What a party! All that’s needed is a song. And the organizers have just the thing: a tune freshly penned by Calixa Lavallée, then one of Quebec’s most renowned composers.

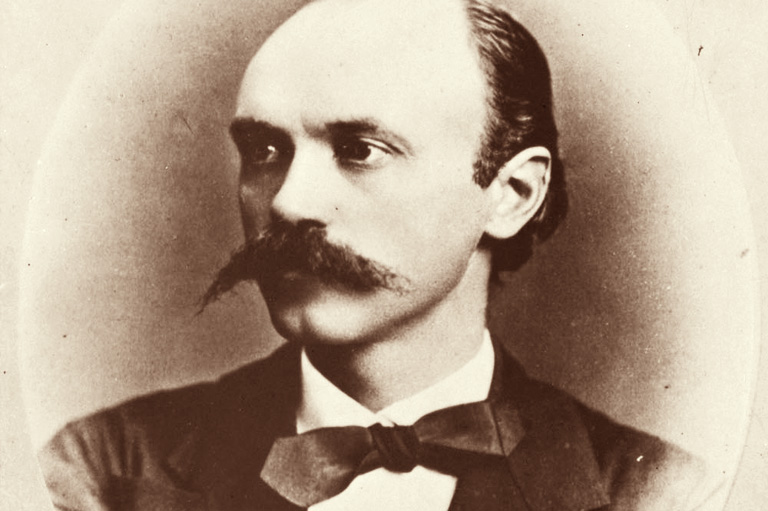

Lavallée hailed from Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec, and his résumé shows that nothing ever changes: He had to go south to succeed. As a young man, he enlisted as a musician in the Union army in the U.S. Civil War, emerging wounded and honourably discharged. He then found fame writing operas in New York, Boston, Paris, and London.

Returning to Quebec in 1880, Lavallée found his compatriots buzzing with plans for celebration. The French population had exploded, and the habitants felt powerful and proud. They asked Lavallée for a patriotic song, which he composed in April 1880. Words came from another son of Quebec, Mr. Justice Adolphe-Basile Routhier.

After the meal at the Quebec City banquet hall, a band of a hundred trumpets struck up, accompanied by a choir. “Electrified by an unstoppable impulse,” reported those who were there, the crowd stood and heard for the first time the brand-new song, whose words existed only in French: "O Canada, terre de nos aïeux!"

In 1891 Lavallée died, penniless and forgotten, in Boston. His song, though, was steadily becoming a hit.

Over the next twenty years, the song swept through Quebec, sung in churches and on all formal occasions; two thousand schoolchildren sang it to the Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V), when he visited Quebec in 1901. The tune then spread east and west.

Having no English words, people across Canada composed their own lyrics, and by the 1920s, English Canadians sang two hundred versions. Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, seeking an official English “O Canada” for the Diamond Jubilee of Confederation in 1927, asked his chief archivist to write Canadian Clubs from coast to coast.

Such clubs were set up by young businessmen to foster patriotism, and King wanted "a copy of the text used by your club." The replies, as preserved at the National Library, show that the city of Stratford sang, “O Canada! Beloved country thou; Hope’s holy wreath adorning thy young brow,” while Toronto sang, "Lord of the lands! Beneath thy bending skies; On field and flood, where’er our banner flies."

But more than half sung a version written in 1908 by yet another Quebecer, Montreal judge Robert Stanley Weir. Rather than translate the French, Judge Weir captured the spirit: “O Canada! Our home and native land.” The federal government chose to publish Weir’s song for the 1927 festivities, and it is the song English Canada sings, with minor modifications, today.

“O Canada” spread in World War II, and by the 1960s had won its place as the country’s national song. But it was still not official. Finally, in the wake of the 1980 sovereignty referendum, the House of Commons showed a rare common purpose, and on June 27, 1980, voted unanimously to pass the National Anthem Act. Three days after its 100th birthday, “O Canada” finally became the nation’s official anthem.

We hope you will help us continue to share fascinating stories about Canada’s past.

We highlight our nation’s diverse past by telling stories that illuminate the people, places, and events that unite us as Canadians, and by making those stories accessible to everyone through our free online content.

Canada’s History is a registered charity that depends on contributions from readers like you to share inspiring and informative stories with students and citizens of all ages — award-winning stories written by Canada’s top historians, authors, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

Any amount helps, or better yet, start a monthly donation today. Your support makes all the difference. Thank you!

Themes associated with this article

Advertisement

You might also like...

Canada’s History Archive, featuring The Beaver, is now available for your browsing and searching pleasure!