Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

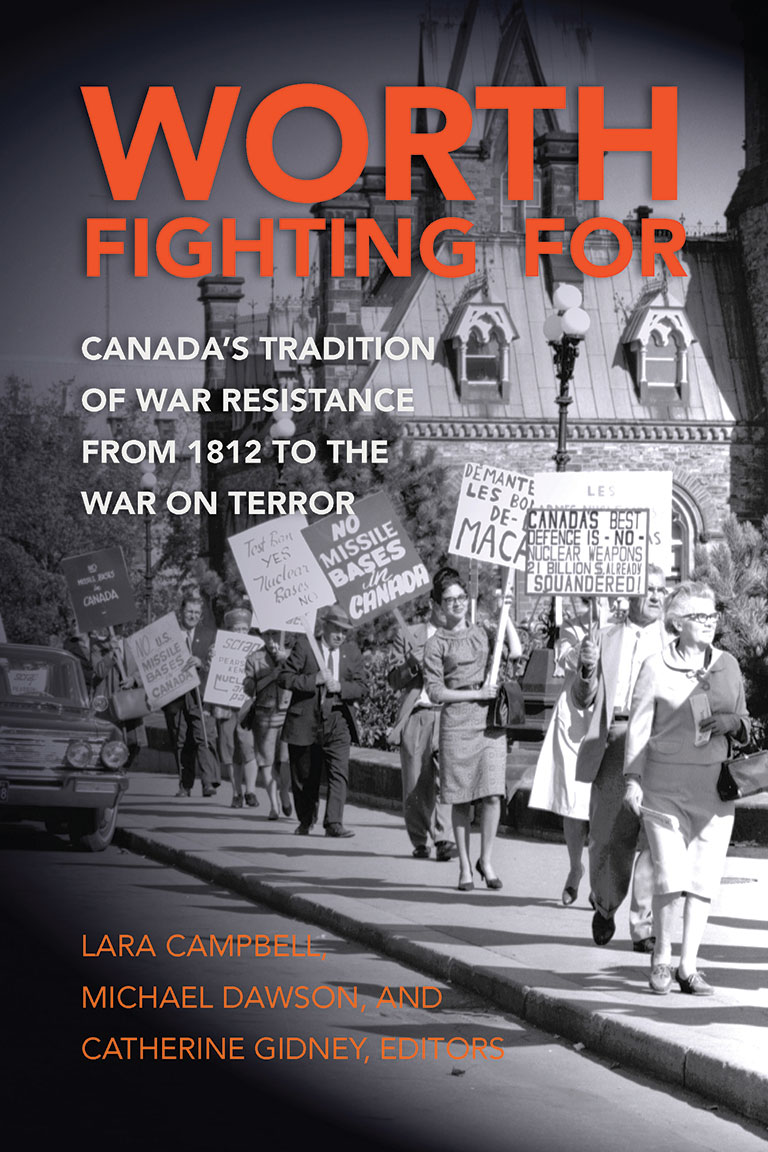

Worth Fighting For

Worth Fighting For: Canada’s Tradition of War Resistance from 1812 to the War on Terror

edited by Lara Campbell, Michael Dawson & Catherine Gidney

Between the Lines

321 pages, $34.95

Does Canada really have its own tradition of war resistance? Are such activities a significant part of our national narrative or merely an occasional side story? Worth Fighting For, a collection of essays published by Toronto’s Between the Lines progressive press, offers an alternative to the military buffs who have dominated the interpretation of history in recent years. The book’s contributors argue that war resistance should be understood to include all forms of opposition to state-sanctioned military violence and militarist culture.

Conscientious objection by faith-based individuals was an early part of Canadian pacifism. Opposition to war might also have overtly political motivations, notably in anti-imperialism, French-Canadian nationalism, international peace activism, or, most recently, objections to the practices of the “war on terror.”

In their focused introduction, the editors argue “that over-emphasizing military history while ignoring resistance to war is a simplification of our past … and the relationships among citizens, dissenters, resisters, activists and the military.” Their book presents seventeen essays that vary in length and depth, exploring older issues such as pacifism during the War of 1812 as well as more modern events.

One recent episode was the 1964 civil disobedience campaign at La Macaza, Quebec — site of a controversial BOMARC anti-aircraft missile base. The author, Bruce Douville, examines this well-publicized protest and explains that it did not succeed in stopping the deployment of nuclear warheads in Canada. Still, he concludes optimistically that these protests helped to create an effective organizing model for New Left activism during the later 1960s and the 1970s.

The help given to many Americans escaping the Vietnam War military draft is the theme of another essay. Contrary to later popular opinion, the federal government did not welcome draft dodgers into Canada. Immigration officials often blocked their entry, while legal changes by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s government made applying for landed-immigrant status much more difficult. It took a broad range of liberal-minded campaigners, together with committed political activists, to open Canada’s doors to an estimated thirty-six thousand Americans.

The most current essay topic deals with the treatment of American soldiers who have sought sanctuary to avoid fighting in Iraq. Canada’s reception thus far has been frigid, with officials arguing that American deserters do not deserve the support given to draft-evaders in the 1960s. Refuge has not been granted here. The essay concludes that this policy is contrary to international obligations.

While this collection is interesting and provocative, I react skeptically because it provides so little evidence on the effectiveness of war resistance. (Note that I also respond skeptically to historians who are eloquent about Canadian identity being nourished by blood sacrifice on distant battlefields.) There are only a few essays where actual numbers are relayed — such as the estimated one hundred protesters in La Macaza in 1964.

There is also a writing style in the collection that infuses some texts with sweeping generalizations, implying how Canadians have seethed in anti-war revolt. “Workers and farmers … resisted the power of the state to conscript,” say the editors about the mood around both world wars. Notice the absence of limiting adjectives. (Maybe some workers resisted, or a few farmers.) Sadly such language reads like a political tract.

We are on more solid ground to argue that war resistance sentiments, expressed clearly and directly, can influence how people think. Resistance may sway political decisions today, or feed the demand for government changes tomorrow.

Altogether, this book provides a refreshing contribution to our country’s history. It conveys a balancing description of some citizens’ views on war and militarism, stressing the need to speak out despite being a political minority. Dissent is not disloyalty. Moral arguments and a peaceable militancy can influence a climate of opinion. Perhaps this sums up the essential tradition of Canadian war resisters.