Discover a wealth of interesting, entertaining and informative stories in each issue, delivered to you six times per year.

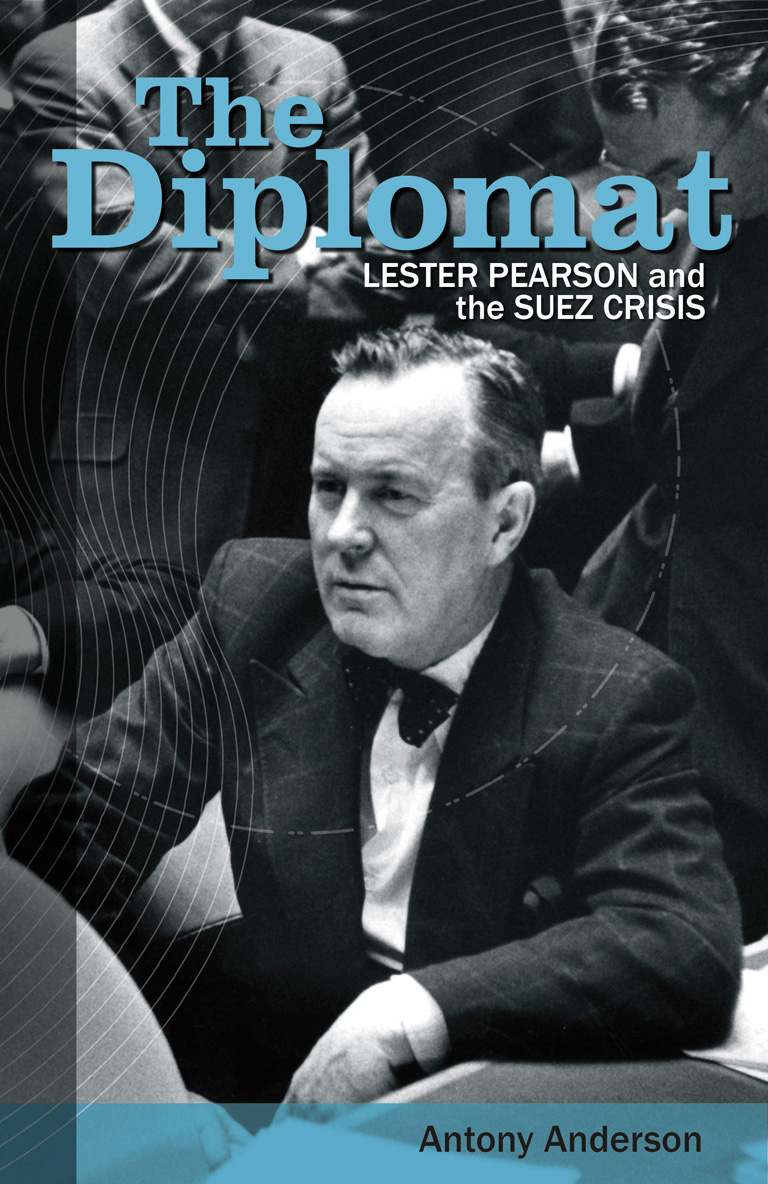

The Diplomat

The Diplomat: Lester Pearson and the Suez Crisis

by Antony Anderson

Goose Lane

400 pages, $32.95

In his introduction to this valuable book, Antony Anderson tells us that he took a long time researching and writing The Diplomat, and that he “resisted and relented” before seeing it to completion. We should all be grateful that he did, because what he has given us is not only a penetrating character analysis of Mike Pearson but also a clear headed analysis of the evolution of Canadian foreign policy and a riveting narrative of the Suez crisis itself.

The book takes a long time building up to the key events in 1956. Anderson is clearly fascinated by the elusive personality of Lester Bowles (“Mike”) Pearson, whose aw-shucks public persona belied a seriousness of purpose, a driving ambition to succeed, and his own personal crisis at the end of the First World War. Drawing heavily on John English’s invaluable biography of Canada’s fourteenth prime minister, as well as lengthy CBC interviews with Pearson before his death, Anderson gives us a discerning picture of a man who managed to get himself into the middle of events and decisions long before he became Canada’s foreign minister in 1948 at the age of fifty-one.

To Pearson’s humanitarian and liberal instincts have to be added a disarming capacity for self-deprecation and an unusual ability to read both a room and a crisis to find an elusive middle ground. He was no pushover and no misty-eyed idealist. But he was value-driven as well as pragmatic, a scholar and a sports fan, a man who was a friend to seemingly everyone and at the same time a mystery to many who were close to him.

There is a long run-up to the Suez story — a British Empire in steady decline, with liberal Canada, and Pearson, caught somewhere between admiration for the British connection and deep frustration at the obtuseness of the imperialists who could not see the increasing mismatch between their pretensions and their impotence.

The author traces Canada’s emergence as an effective “middle power” during Pearson’s rise through the ranks of the foreign service and his transition to politics. Anderson also gives a compelling account of Canada’s — and Pearson’s — pivotal role in the creation and recognition of the state of Israel after the partition of Palestine.

Pearson, and Canada, were thus in the right place at the right time, faced with a huge miscalculation by the Israelis, French, and British and their botched invasion of the Suez Canal in the fall of 1956. As an individual, Pearson was known and trusted by the leaders and foreign ministers of the countries involved, and he had a deep appreciation of what the United Nations could and could not do. The UN was then a smaller place, and Canada’s critical role during and after the organization’s 1945 founding conference in San Francisco allowed Pearson to influence events in a way that has scarcely been matched since.

Anderson’s book is also a useful antidote to some of the romanticism with which many now look back upon these heady days of Canadian diplomacy. Pearson’s efforts were highly controversial in Canada, and there were slips and embarrassments along the way. The establishment of the United Nations Emergency Force, or UNEF, was a slapdash affair and had the central weakness that Egypt could ask the peacekeeping troops to leave at any time — which is precisely what happened in 1967.

But it’s all about the art of the possible, and Pearson accepted that as the reality within which he had to work. He was an idealist who worked in a world where hard decisions had to be made quickly, and there has not been a more effective diplomat in our time. This book is to be commended not only for describing a critical moment in the life of the world but also for its humane and thoughtful description of the man in the middle of the hurricane. At a time when many are talking about a return to “Pearsonian values” in our foreign policy, it is a truly welcome addition to our understanding of both the man and the era in which he worked. Times have changed, but if the world needs more of Canada, it certainly needs more of Lester Bowles Pearson.